Last year, almost half a million pilgrims arrived in Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain. Their destination: the medieval cathedral where, legend has it, the bones of St. James the Apostle are entombed. About 47 percent of those who made the journey did so for purely religious reasons, according to statistics released by the Pilgrim’s Reception Office. But why did the rest choose the Camino?

Some of these pilgrims might describe themselves as spiritual but not religious — presumably, they feel there is something about the experience of walking the Camino that they can benefit from even as non-Christians. But I’m not sure dropping religion is quite so easy.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

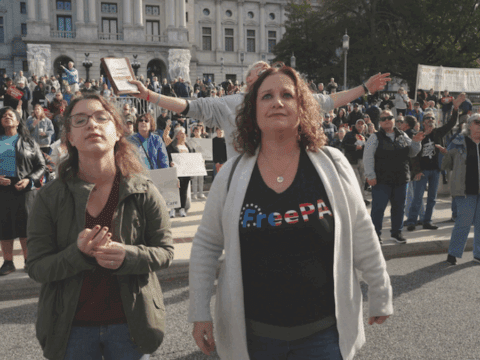

Nancy Ammerman, a sociology of religion professor at the Boston University School of Theology, believes the idea that spirituality is distinct from religiosity is essentially a successful rebranding exercise: people take the aspects of religion they like and label them “spiritual.” Religious traditions have become a spiritual salad bar where each of us fills our plate with our favourite items. We are constantly searching for the perfect combination of ingredients. Walking the Camino is like bacon bits, adding a nice salty crunch to whatever else is piled on our plate.

A spiritual seeker on the Camino won’t avoid religion. One is walking toward the tomb of an apostle — that seems pretty religious to me. But the Camino’s very existence also depends on Spain’s particular religious history. St. James’s tomb was discovered around 813 CE, during Islamic rule of the region. It provided Christian authorities with a pilgrimage destination that could help bring more Christians into the area.

Religious practices like pilgrimages don’t necessarily work as well if we remove all their religious content and context. Yet that is the very idea behind the so-called spiritual salad bar. We want access to spiritual wisdom without having to understand complex metaphysical systems. We want spiritual values without having to follow religious rules. We want self-transformation without having to associate with religious institutions. And by insisting a technique can be spiritual instead of religious, we think we can achieve these goals.

The late Huston Smith, an American author and scholar of religion, argued that a religious experience does not always result in becoming religious permanently. Perhaps a spiritual seeker on the Camino will experience something significant — a new awareness, insight into the role of physical suffering or the power of the pilgrimage community. But without conviction that these insights are true, they won’t return home truly transformed.

- A pilgrim seeks meaning on St. Cuthbert’s Way

- My year as a hermit

- Involuntary pilgrim: A 20-year journey with cancer

I’m not trying to talk non-Christians out of their dream Camino adventure. But I do have some words of caution.

Spiritual shortcuts skip over doctrines, authoritative structures and systems of values, but religions require submission, cultivation and fidelity. Engaging in spiritual practices without understanding their religious or social context can lead people to associate with institutions or ideas that are against their own values. This can unsettle their sense of self.

So go ahead, plan to walk the Camino. But maybe also delve a little bit into the religious history and meaning of it. Otherwise, you might get a lot less, or more, than you bargained for.

***

This article first appeared in Broadview’s September/October 2025 issue with the title “The Secular Pilgrim.”

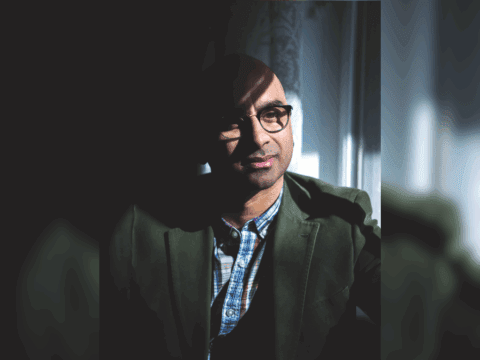

Liz Bucar is a religious ethicist and professor at Northeastern University in Boston. She is the author of Stealing My Religion: Not Just Any Cultural Appropriation.