The first time Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, in 2016, Rev. Danté Stewart’s life began to disintegrate. At the time, the minister, poet and writer was the first Black preacher at a mainly white evangelical church in Augusta, Ga. But as Trump’s divisive messages began to take hold across the nation, Stewart could hear those same ideas emanating from his pews.

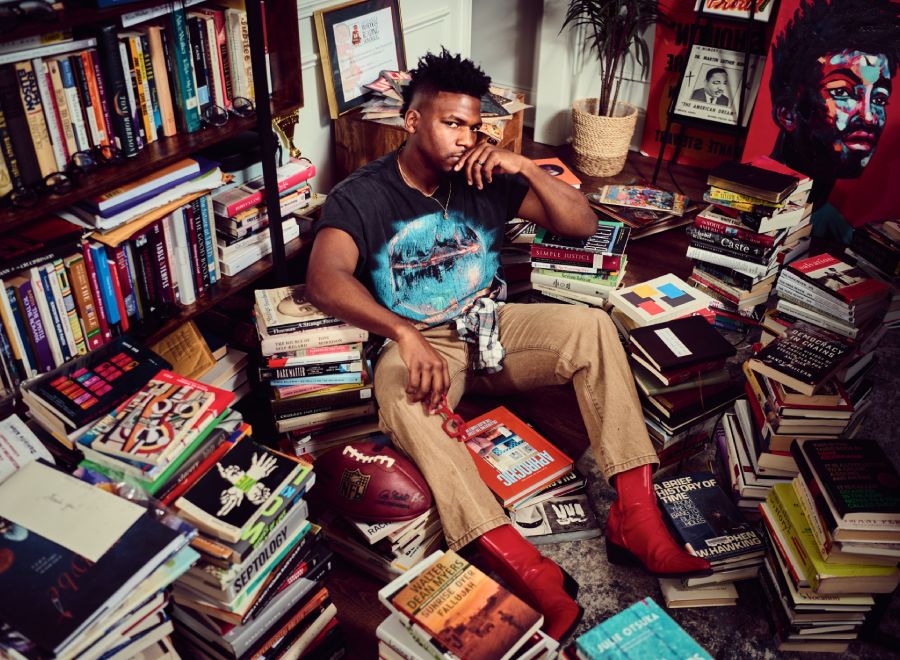

He left that church and went on a voyage of self-reflection and discovery, finally finding both a place and a powerful voice in Georgia’s Black Christian community. His journey is detailed in his semi-autobiographical book, Shoutin’ in the Fire: An American Epistle, published in 2021. That same year, his best friend, football star David Patten, was killed in a motorcycle crash. More recently, and as a swing-state resident, Stewart was determined to use his voice and influence to make sure Trump did not get into office again.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Now, in the first weeks of Trump’s second presidency and with Easter approaching, Stewart names the grief many are feeling and charts the struggle to return to joy. He finds lessons in the story of the two disciples on the road to Emmaus who see Jesus after the resurrection.

As a minister, my job is simple:

to go to the places people often don’t go in order to bring them safely through. That is to say, my task is to courageously face deep human darkness and wrestle with it in its most terrifying forms in hopes to “salvage the bones,” to borrow the title from American novelist Jesmyn Ward’s book.

But in 2022, depression unravelled my sense of self, my sense of time, my sense of wonder, my sense of where I stand in the world. It destroyed the distance between who I once was, who I am becoming and the bridge between the two.

Since then, I have been on the search for a deeper kind of healing that allows me to look in the mirror, remember the life I have lived and love what I see. I have spent countless hours talking to my therapist, afraid it’s going nowhere, afraid my heart can’t be healed. Since then, more children have been murdered in schools, and more Black people murdered at a grocery store. Students have encountered book bans and mass arrest. It’s easier to own a gun than it is to get health care. We are collectively struggling with exhaustion and fear and terror and sadness and confusion — not too far off what everyday life was like back almost 2,000 years ago when people awaited a saviour and a friend. And then there is what the late Swiss-American psychiatrist and grief expert Elisabeth Kübler-Ross calls “anticipatory grief.” Donald Trump is back in the White House. We had hoped to stop it; we had hoped we would find a way, and we could not. Now, we see only more fear and sadness that is visceral because we know what the past has been and done.

The question I can’t get out of my mind is this: what can a broken heart do?

As a public theologian, I am expected to have the answers, to be certain, to somehow provide a prophecy of how things will be in the end and how things are supposed to be in the now. Yet, I have been emptied of certainty. The older I get, the more I realize that the greatest threat to me and my broken heart is not my doubt but my desire for certainty. And that’s something that nothing — especially a shattered heart — can provide.

In divinity school, we are taught that love and grace remain even when pieces of ourselves and the world implode. We learn that the power of telling the story of what happened remains even when hope leaves.

And here is a story. A tragic story. A heart-wrenching story. A story so real and so unnerving and yet so beautiful and so human. An Easter parable. A journey that at times feels like it is headed nowhere and everywhere. It lingers in the darkness of that terrible crucifixion night, with no certainty that resurrection will come. “There are years that ask questions and years that answer,” writes the southern novelist Zora Neale Hurston. Easter does both.

***

It is Thursday, the second day after the 2024 presidential election. My wife is out of the country on a military assignment. My two children are lying beside me, and all I can do is rub their backs. I am travelling down a rabbit hole of possible future timelines. It feels like a nightmare. But it is not: it is as real and as painful as it was eight years ago, the first time Trump was elected. Just this time is much worse for me because now I have children, and now they are in that story.

The first night, I can’t get to sleep. As the states on the screen turn red, I pace the room, go to my daughter’s room where both my children are asleep, get up, pace again, until from sheer exhaustion I collapse beside them to get one hour of sleep. No, not this again. My mind goes back to the pain and trauma Trump wrought on the nation and its citizens during his first term in office, from 2016 to 2020. No, God, please not this again, I think, rubbing both of my children’s backs as they sleep.

It has rained the last two days as if Georgia, the swing state where I live, is in mourning. They say when a storm comes, nature knows: the birds take shelter and an eerie silence echoes in the distance. Some five weeks before election day, we went to bed awaiting the arrival of Hurricane Helene. That Friday we all got up, looked outside and couldn’t believe the devastation.

On this morning after, I look outside in the darkened sky and hear the dripping from a similar torrent from the night before. What have we awakened to? No, God, not again.

My daughter is first to awake, then my son. The clock reads 7:23 a.m. I am late. Too tired, too worried, I can hardly find their underwear and shirts. I’m pacing up and down the stairs trying to find some sense of normality in the discombobulation.

If I can be honest, this morning, and this week for that matter, I am and will be sad. Distraught. Numb. It is a sadness that makes my stomach tight. I can hardly eat, hardly think. I am attempting not to feel a burning and indignant rage. I am tired. We are tired. Exhausted.

“Daddy, what’s wrong?” my son asks me, feeling my mood engulf the room.

“Daddy is a bit sad,” I say to him, telling him about the election, how it didn’t turn out the way we wanted, telling him the history of Black people in politics. I say that sometimes you win and sometimes you lose, but every time you learn. “I just don’t know what is going to happen,” I say.

He can barely understand. He is six. He is a Black boy, like me. I feel angst rise up as I try to prepare him. I know he will be at school with children who have heard their parents breathe the oxygen of anger and rage from their computer screens, televisions and radios for the last few years. I tell him: “Be courageous, respectful, kind. If someone is mean, be sure to let me know.” The anxiety deepens as I get them dressed, a burning anger at the thought that what I faced, what my mother faced, what my grandparents and their parents faced, must now, at six years old, be the lesson he must learn.

There are those who say, “America deserves to suffer with Trump because of the bad choices the country has made.” And I just want to say, no. No. Having lived through the first Trump years, having seen what people became, how we suffered immensely, how we constantly had to deal with what he unleashed — no, none of us deserves this.

It’s just that this country is racist and sexist. It’s staggering to witness the steady descent into a kind of fascist darkness. Hardly any words can describe what it feels like to be Black and American and determined and blamed and hated, living in a country that would rather destroy itself than acknowledge your existence, protect your children, honour your story and change itself.

And we don’t deserve to endure the collateral damage of the choices of hateful people. Not us. Not queer and trans people either. We don’t deserve to wake up this way, to show up to work with people who hate us, to explain to our children what happened, to not be overcome by despair. We are tired — and we have held the country together only to be bruised and betrayed by it.

***

“It’s kind of like I’m watching a movie from the outside in, like that’s me but not me at all,” I tell my therapist as I sit in front of the computer screen. It is night. The stars show themselves through the window of the room I’m in, my son’s playroom. In the background, the sounds of my children playing with my wife downstairs filter into our session. My therapist listens. Writes some notes. Looks up again. Writes some notes again.

“Say more,” he says, bending his head to the side, writing again.

“I guess to be young and gifted and Black is to be haunted by time,” I say, laughing, putting both my hands together, moving them back and forth. “I don’t think I’m afraid of death as much as I think I’m afraid of time.” Growing up in rural South Carolina, I encountered death so much. The choices are limited, the resources are few, the determination is deep and you live with an internal clock that haunts you because you are so aware of how precarious existence can be and how swiftly death can rob.

I tell him about rubbing the head of a man who has lost time, my grandfather Jonney R. Albert. Toward the end of his time here, dementia gave him a jerk and twitch that mimic the sort of quickening that the Spirit brings when the service back home is high. So fast, it conjures. I rubbed his head as a gesture of my presence until he finally sat down in front of a small plate my aunt made him that looked to be the same amount of food my two-year-old daughter would eat.

My granddaddy was a short, sharp and determined man. The greys of his head fell a bit to the side as the years made a barren land of his scalp. The ends of his fingers were bony, the veins like rivers running toward the ocean of his brown skin and greased with the petroleum jelly that also greased the hands of my grandmother. His eyes were a touch of gray, glassy almost, with a hint of blue. We always thought he had a bit of Native American in him because of the colour. The story in the South was that Black boys with green eyes were cursed with charm; they could bring down kingdoms with just one look.

We don’t deserve to endure the collateral damage of the choices of hateful people.

The last time I saw him, I held his hand in mine and whispered in his ear. I told him about the things I remembered, the things I had to let go of and the things I’d forced myself to forget. I knew he couldn’t understand the words I spoke, but as my heart was breaking, I told him about the sheer joy it brought me to be with him and how good it felt when I rubbed his head and repeated to him old stories.

***

Living in the south, first in South Carolina, then in North Carolina and then in Georgia, gives you a strange sense of the country — and of the deeper rot beneath the surface. “I was born in the South, I live in the South and I’m going to die in the South,” my grandmother Margaret Elizabeth Albert would tell me. Ninety years old, she still lives in South Carolina. She and granddaddy were married after he came back from serving in the Korean War. She talks in a soft high-pitched tone that is somewhere between pleasure and resolution.

Now, most times we are together, she tells stories of years ago, as if the past is at the tip of her fingers. Surely, for a woman who has seen so much in 90 years of living, to travel through time is better than to become defeated by it. So, in some sense, the affirmation that she was here, remains here and will be here in the end is a witness to the forever presence of life: the aura, the vibrancy and vitality that will never leave long after it has departed to elsewhere.

More on Broadview:

- In the wake of another Trump win, this biblical figure gets our sorrow

- Whose Christianity does Trump want to protect?

- Why white evangelical voters back Trump

Here in the South, we see clearly what damns this country, the white rage and revenge, the allure for Black people of being protected and praised by whiteness, the technology that grows the wedges and fault lines in our social lives, the partnerships between powerful people to sway the affairs of the world.

And the rot is this: we live in a country of bullies, American bullies. Bullies who can only feel powerful when someone is less than them, who can only feel free when another person is bound. We live in a country where racism, white supremacy and sexism do not die with time but are passed on from generation to generation. We live in a country where we have to prove our humanity and fight for it. We live in a country that takes more than it gives, that pains more than it protects. And we are tired.

There is grief, the kind that happens when millions choose to further your erasure and oppression, when people make a mockery of your pain, when people smile in your face and say they stand with you only to betray you. It’s grief in the inability of our neighbours to show any whit of concern about dismantling the world in a way that helps their child but harms ours.

There is fear for our children and their future, knowing the world is immediately a less safe place, where money means more than human lives, where misinformation is mightier than the bomb, where it seems all trust and goodwill between fellow citizens is eroded and sacrificed on the altar of power, revenge and fear.

It’s bitter disgust at what one man can make people do and say in the name of fear, and that many are about to be emboldened again to become the worst kinds of humans they allow themselves to be.

There is grief in the anticipation of what we know will happen. The impending doom that tomorrow will bring because you know what yesterday has been. It’s grief about the past we wear in our literal bones. It’s in the reading of books about failed empires and a bigoted republic and a radicalized populace, and the resistance against it, only to find yourself not reading history but living it. It’s in the ways law and religion have been weaponized, in the way the country is convinced that the worst kinds of history can’t happen here, that we are immune to implosion, that we can just muscle and survive it. It’s in the ways we had foolishly hoped that people would choose differently.

***

“What do you want from this?” my therapist asks. I look at the clock. We’ve already been talking for almost two hours. More than the 45-minute appointment allows. “What do you want?”

“I want to feel whole,” I say. “I want to be out of the cave,” I say. “I want to feel alive,” I say. “I want to remember.”

“You don’t have to fill your mind,” my therapist replies. “You have to heal it.”

I laugh because his cadence feels a bit performative, almost as if he was waiting to use the phrase, a cliché that would make me smile. Well, he succeeds. It is the first time I laugh this night.

“So what do you suggest?” I ask him.

He puts his right hand to his chin. “You like music, don’t you?” he asks.

“Yeah,” I say.

“Okay, that’s it,” he says. “This is what I want you to do: I want you to sit on that orange chair, put your headphones on, close your eyes and for 15 minutes, I want you to listen to music that brings you joy.”

“Now that I can do,” I reply.

Later that night, I sit in the chair, the room lathered in the smells of vanilla and sandalwood from a candle on my desk. I lean my head back and stare into the creases of the ceilings, the same place where my life bounces from wall to wall. I turn on music. I close my eyes.

***

There is grief, that heart-shattering gaze as you face your elders when you see half the country attempting to erase every step toward liberation they’ve taken. The decades of work many have done to make the nation better being rolled back with satisfaction, evaporated in the flames of people who want revenge. The reality that there are people actually intent on destroying this nation we have built.

There is grief of being emptied of words and feeling. Of wanting to be angry but failing to have the energy. Of convincing those who don’t live where you live or don’t look like you look that the damage done to your body and mind will be exponentially worse than it was the first time. Of attempting to find solace and grace, of not feeding your worst impulses, of believing that time is on your side.

I am speaking of bullying, a bullying that breaks my heart. But I also speak of tragedy, an American tragedy. I am almost at a loss for words when I consider the fact that this is a fight that we just may not win. The forces against liberal democracy are as old and as deceitful as they are new and destructive, and they are wreaking havoc on every aspect of our civic life. We the people are not the people, but through decades of manipulation have been ushered so deep into our silos that we are a country of states that are united in name and place only. We are not okay. This country is not okay, and the story historians will tell of this moment is that we allowed the rot to consume us, that we had a chance but chose sickness.

Nothing is promised here. But we must be determined to save what is ours. And to me, Black Americans have done that. We’ve not had faith in the country but in ourselves. One day, we will defeat the hatred and un-kindness so desperately plaguing our nation, but sadly, that day is not today. Today is a day we cry. Today is a day we hold our children. Today is a day we thank our ancestors and elders for showing us the way. Today, we thank everyone who worked hard to beat back the darkness. Nothing more. Nothing less. I remember these words, from poet Langston Hughes:

I am so tired of waiting,

Aren’t you,

For the world to become good And beautiful and kind?

Let us take a knife

And cut the world in two —

And see what worms are eating

At the rind.

From where I stand in the world, we are weeping. The world is heavy. I wish it were different.

From where I stand in the world, we are weeping. The world is heavy. I wish it were different. We know the past is on our heels, the spirit of white rage, the troubling waters that often consume us and we must face it once again. We are lifting what we can, mourning, holding our children, preparing for what difficult years await us.

We know that, as the writer and activist James Baldwin said, it will be hard. We know, as he said, that we come from sturdy peasant stock, those who picked cotton and marched for freedom and won legislation and built this nation, and in the midst of it all, held this nation and its soul together with dignified hands. We do not deserve to give or endure more than we already have. Our weary hearts have already given enough balm to heal the nation’s wounds. But from that stock we come nonetheless, from that stock we arrive to the mourning, waiting for the clouds to pass and as they move, we move along as well.

How do we find a way to move along? What can a broken heart do?

***

It is of no wonder that lovers are afraid to admit that love is sometimes a useless thing. The varying degrees of human experience bear witness to the words of the great Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe: “Things fall apart.” Be they by happenstance or by choice, no good thing can last forever. And here is the bad news: some good things never start at all. I have watched the night sky, attempting to call the constellations by name. Far too many, I suppose, and far too distant a timeline to know what they call themselves.

Psychologists and doctors tell us that in the last moments of life, when, as some ancient sages would say, a human is about to return to God or eclipse those stars, the first thing to leave is consciousness of space and time. The dying person will begin to withdraw from the external world. The colours will begin to blend into one another. Some say the dead reach back toward the living. They say the living begin to see and be comforted by the dead.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that first Easter and the story in Luke’s Gospel about the disciples on the road to Emmaus. It’s three days after the crucifixion. Those two had lost faith in a moment of great struggle. They had been with Jesus. They had seen him grow in wisdom and stature, had seen him challenge and heal, had seen him nervously get away from crowds, his social anxiety getting the best of him.

Who could deny him that? Not even God could overcome what burdens human beings can become. In those quiet moments, we are not able to see him or know what conversations he had with himself, but what is known for sure is that sometimes getting away can be the best thing. Silence, they say, can sometimes be the best teacher.

The disciples had left Jerusalem after Jesus was brutally killed. His life was taken in the most public of ways. This was what we would call a lynching — the disrespectful disregard for life; the ending of it at the hands of evil people. And we know no one becomes evil overnight. People are made evil by the myriad choices that are made for them and that they make for themselves. Those men had made a choice: Jesus is to die — and he does. And his disciples are lonely.

In the journal next to me that I have been carrying for weeks now, a bitter gap sits between the dates Sept. 1 and 9, 2021. In between, a chasm. My best friend, National Football League star and three-time Super Bowl player David Patten, died in a motor- cycle accident on Sept. 2, 2021. There was nothing left to say. I had come to the end of language, the end of words.

I wish I could say that regret and friendship can overcome heartbreak and time. I wish I could say that standing at the fallout of a best friend’s fatal wreck can heal a formless gap in my psyche and soul. I wish that every bloody dream can end in being awake and a new day beginning. I have wondered if language, at the end of the world, is the secret gift of life, the reminder that an untimely exit is not the ending of all things. There is haunting, yes. There is regret, of course. But the greatest of these things is love.

The French philosopher Roland Barthes tells us, “Despite the difficulties of my story, despite discomforts, doubts, despairs, despite impulses to be done with it, I unceasingly affirm love, within myself, as a value.”

The disciples on the road to Emmaus say to each other: “We had hoped he would be the one.” And at that moment, Jesus appears without letting them know. But they knew, we all know when hope appears. We can feel its presence, can feel its energy like a divine hug from another world. And they run, they run back to Jerusalem, the place where it hurts. They run back to their friends to tell them that Jesus has appeared. They refuse to let this world go on lonely. “Didn’t our hearts burn,” they say. Isn’t that an apt way to describe what we feel when words find us again? When the page is turned and we can finally utter a breath?

Even broken and confused words can still be prayer. I have prayed so many times with my hands and with my arms and with my stomach and with my legs, saying to this world like the disciples did: “He is alive.” Death is not the end of a thing but the beginning. Resurrection is far more ordinary and far more powerful than just being here when we were once not. Resurrection is about turning to those who have all but given up and, like Barthes, saying, “I unceasingly affirm love.”

Here we are together this Easter on the precipice of a world that is dying and a world that is being reborn. Nothing we possess will ultimately save us except the words from within that bear witness to the hope that remains. And here I dwell, like the still morning when the snow falls, telling everyone: “What a beautiful kind of dying.”

***

Danté Stewart is a minister, public theologian and author based in Augusta, Ga.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s April/May 2025 issue with the title “What Can A Broken Heart Do?”