In mid-December, I was invited by an NGO that works in the north to provide art therapy in three remote Saskatchewan communities, about 60 kilometres from the Northwest Territories border. Our hope was that art therapy would address the incidents of suicide and domestic abuse that are so prevalent in those communities. I had worked for five years at the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge in southwest Saskatchewan — a federal penitentiary for Indigenous women — and felt confident that my experience there would prepare me to work in these Dene communities. However, for many of the women I worked with in the penitentiary, there was more motivation to be involved in conventional therapy and my program was often the only creative option available there.

Fond-du-Lac has about 875 residents, is on the eastern end of Lake Athabasca and is only accessible by air. Stony Rapids, even smaller, is about 15 minutes from there by air and adjacent to Black Lake — the largest community.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Like so many Indigenous communities across the country that have been tainted by colonialism, there is a high incidence of mental illness, trauma and abuse. I hoped that art would enable the people I worked with to tell their stories and express repressed emotions. I took oil pastels, clay and large sheets of newsprint. In the groups I worked with, suicide surfaced again and again in art or conversations—a nephew, a child, a cousin, a best friend. Every family has been affected.

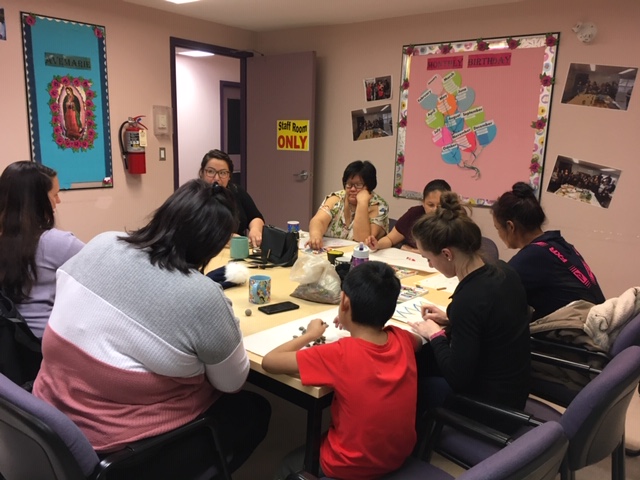

A women’s group had been arranged in the band office in Black Lake for 7 p.m. on a Tuesday night. At that time, it was pitch black, and during that mid-January week, the temperature never rose above -30 degrees Celsius. The women are mainly single mothers—they had no choice but to bring their children. The children, delighted with the art supplies, took spaces at the table in the small room we met in. There was no opportunity for the mothers to concentrate on their own stories, which often involved abuse.

Despite this, one woman whose son had died by suicide in May drew green grass and nothing else in the picture except three distinctly different clouds at the top of the page. Her life was empty without her son. She identified the clouds as her three living children that keep her going. I noticed in the top-right corner that she had not coloured in an outline of a fourth cloud. I suggested to her that her son was still in her life, but in a different way. That seemed to help her.

If I had been able to work with this woman again, I would have invited her to begin to put other things in the picture. But our time together was exceptional and I didn’t get the opportunity to hear others’ individual stories. Partway through the evening, I decided it was more important for these women and their children to enjoy their night out than to try to do art therapy.

More on Broadview: ‘Photography was the way that I could share different Indigenous realities’

Working with the teenagers was also a challenge. Their favourite gym period had been replaced by art therapy. They spoke Dene among themselves, teased each other and laughed at anyone who offered a comment. Once again, I gave up.

But one event stood out for me as having great integrity in itself but also underlined for me the value of art therapy despite difficult circumstances. One boy in Grade 8 drew a cabin all alone in a huge expanse. With great pride, he told me that in early December, he and his father had travelled eight hours north by snowmobile deep into the Northwest Territories. They camped in the cabin he had drawn and in the course of a week, shot 20 caribou—enough food to feed their family for the year. This young man was living his culture and following his tradition—and having an unforgettable experience with his father. I was quite moved by his story and his deep connection to his Dene ancestors, in whose footsteps he was following.

My two weeks up north reminded me why I had become an art therapist and reinforced for me why it is so important to do this work in these communities. Portraying images is basic to us as human beings—we imagine long before we can speak. Spontaneous art is a natural and instinctive way for people to tell their stories. The creative act of drawing, painting or working with clay cuts through pain and anguish and taps into one’s inner spirit. The creator has control over what to paint or draw and which art materials to use. Art also allows for the expression of repressed emotion—pounding or wringing clay is a safe and effective way for victims of abuse to punish the abuser.

I saw many benefits of art therapy in these communities despite the difficulty of doing conventional art therapy. One woman who was visiting her dying father used the art to help her accept his death; another used it to grieve a lost son; for the boy who had gone with his father to hunt and provide food for the family, his picture showed an important part of his story.

It was a privilege for me to work in these communities; we must find ways to ensure that art therapy can continue to be part of their life and work.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

This article is extremely insightful. Art Therapy is just what is needed to confront suicide, abuse and trauma inflicted by colonialism. Thank you Mary Sanderson for your good and important work. You are a brave and courageous woman who makes a difference in the lives of troubled people.

Don’t give up; you are giving others hope and empowering marginalized individuals.