Imagine being in the remote mountains of northern Ecuador in a cloud forest in the dark of night with a fungus expert, a fabled musician, an activist Colombian lawyer and a celebrated nature writer. All of you turn off your flashlights and see that the trees, stumps and fallen branches glow with a “yellow-silver brightness that comes from deep inside the object it illuminates.” This is the rare sight of living mycelial light made by kilometres of fungal hyphae woven through the wood like a lustrous stream.

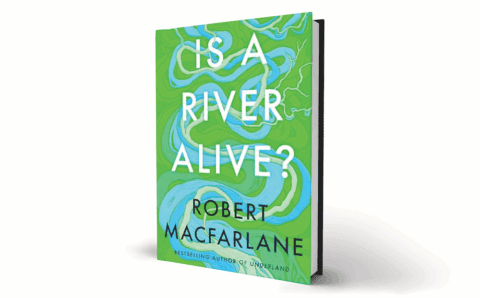

So begins the first of three quests on which Robert Macfarlane takes the reader in his latest book, Is a River Alive? Macfarlane, the celebrated writer in the scene above, has spent a storied career putting language to the places where landscape and emotion intersect. He is also a poet, lyricist and professor at the University of Cambridge in England. His most famous book, Underland (2019), explored the geological underworld in caves, catacombs and a subterranean dark matter lab.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Now, his focus has turned to the legal and Indigenous movement advocating for the rights of nature. Rivers are an obvious place to start in this reimagining.

“Muscular, wilful, worshipped and mistreated, rivers have long existed in the threshold space between geology and theology,” Macfarlane writes.

More on Broadview:

- Using Indigenous wisdom to save the Martuwarra River

- We’re halfway through a 12-year deadline to keep earth habitable. Can we get there?

- How should we navigate the climate crisis?

As with other parts of nature, humans have remorselessly pressed rivers into use: polluting, damming, stealing, drowning, diverting, harnessing and killing them outright. Today, few of the planet’s major arteries run free, and few are swimmable. Some rivers exist only as ghosts trickling unseen and forgotten beneath concrete streets, including 20 in London, U.K., alone.

In his book, Macfarlane goes to Ecuador to find the origin of the River of the Cedars, born in a cloud forest now at risk from mining companies. Next, he takes us to the dying Adyar River running through Chennai, India.

And finally, we go on a lengthy, death-defying kayak trip along the mighty Mutehekau Shipu, or Magpie River, part of the traditional territory of the Innu of Ekuanitshit in eastern Quebec.

The first natural entity in Canada to be granted legal personhood, it remains under threat of damming for electricity.

The further Macfarlane travels, the more he becomes subsumed. On the Mutehekau Shipu, he is literally drawn into the river, “as if some vast and unknowable other life-way is scanning me, echolocating me, clicking away on frequencies far beyond the hertz range of human ears or minds.” His language becomes looser and more poetic. The final paragraph of the final journey is a single sentence of 505 words.

An aria.

The book gives us an unambiguous “Yes!” in answer to the question of his title. But it’s far more than that. Macfarlane has written a new myth for our species, a parable not just of renewal, but of resurrection that aims to save us all.

***

Alanna Mitchell is Broadview’s features editor and an award-winning science journalist. Her books include Seasick: The Global Ocean in Crisis. She lives in Toronto.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2025 issue with the title “The World’s Arteries.”

I am so grateful for the post on FB that reconnected me with Broadview magazine. My subscription lapsed about a year ago and I didn’t resubscribe because there’s so much to read online now. But the article, Are Rivers Alive? drew my attention on the Broad View church site… and the author, Alanna Mitchell is someone I know! I met her in 2010 and she interviewed me about schools and the importance of physical activity, for students, throughout their day. It transformed my teaching and I never had a chance to say how much the increased physical activity benefitted me too! Can hardly wait to read more!