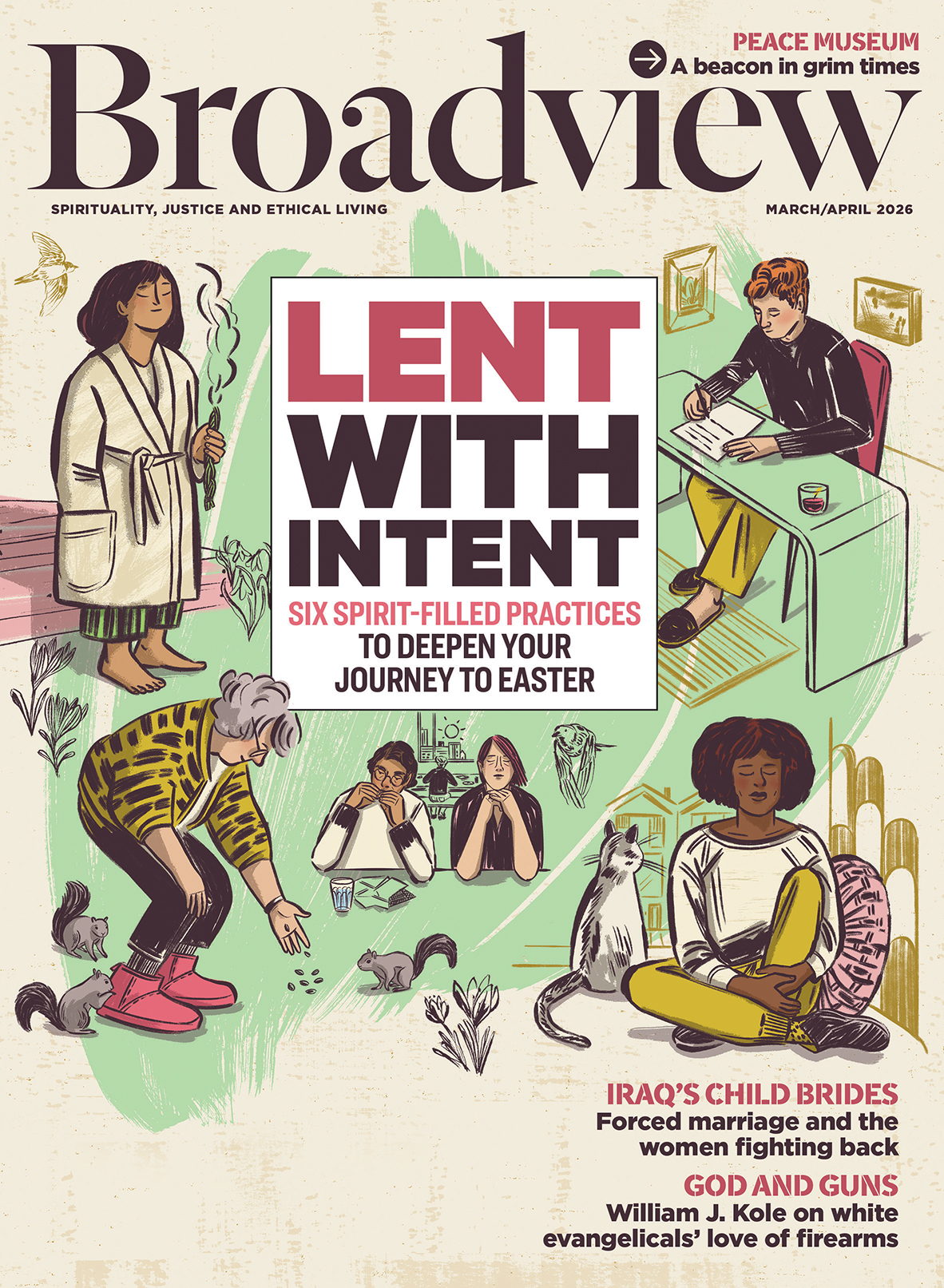

We start our pilgrimage in the ruins of Melrose Abbey in the Scottish borderlands, a medieval monument to the enduring bond between religion and politics.

It’s a cloudy, cool day. I can taste the remains of a sweet heritage apple on my lips, bought for a few pence at the walled orchard in the abbey’s Priorwood Garden a few minutes ago. I and my four fellow pilgrims are at the start of an eight-day trek of about 100 kilometres through the forests and hills of these historically disputed lands between Scotland and England. It’s as if you can still feel the skirmishes, the bloodshed, the passion in the windy tang of the moors.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

I am walking in the footsteps of Cuthbert, the seventh-century Anglo-Saxon saint who was prior of an earlier iteration of Melrose Abbey, a faith community with long ties to the monarchy. Cuthbert went on to become bishop of Lindisfarne, another politically powerful British monastery, which is on Holy Island, the tidal isle off the coast of England where our pilgrimage will end. If, that is, I can make the journey. I’m worried I won’t be strong enough to get through.

Cuddy, as he is still affectionately known, was famous for self-denial and for miracles performed both in life and in death.

In life, he was said to cure people of demons and sickness, even from afar, and once prayed away a rampaging fire that threatened his nursemaid’s home. In death, water mixed with soil that had been wetted from the washing of Cuddy’s corpse cured a child’s howling madness.

For him, life was a permanent, extreme Lent. Sleep was a dangerous temptation. Food and warmth were indulgences. At night, he would wade into the ocean up to his neck and pray in the waves until dawn. As the sun rose, he returned to shore and finished praying on his knees. Otters, it is said, followed him onto the sand, where they warmed his toes with their breath and wiped his feet dry with their fur. Once, after he chastised crows for stealing straw from the roof of his guesthouse, the birds appeared with a penitential slab of bacon fat, which he allowed visiting monks to use to grease their shoes.

Cuddy spawned a cult that endures today. He’s still thought of as the unofficial patron saint of England’s north. St. Cuthbert’s Way, the traditional pilgrimage path whose route is marked by medieval crosses, formally opened nearly 30 years ago and is so popular that a whole industry has sprung up to support pilgrims like me, including hotels, restaurants and a transport service for our luggage. Cuddy, a 2023 novel about his life by Benjamin Myers, won the Goldsmiths Prize, a British literary award.

Durham Cathedral, a two-hour drive south, is one of Britain’s grand temples to Christian faith and a UNESCO heritage site. It was built to contain Cuddy’s bones and remains a shrine to him. His bones lie there still.

This route I am on was the path Cuddy walked in his day and part of what his entourage of monks trekked in reverse more than 1,000 years ago while carting his corpse from Lindisfarne through the borderlands and then south to what would eventually be the site of Durham Cathedral. They walked to preserve his bones from Viking marauders, to keep his memory alive, to enhance his brand of Christianity. They succeeded.

As I shoulder my backpack and begin today’s steep climb up the Eildon Hills, I know that I, too, am on a journey of trial and sacrifice in the modern British wilderness. But what am I trying to find?

***

The fact that Cuthbert is still known today, and that people like me can follow a heritage pilgrim’s way named after him, comes down to his role in the anguished seventh-century controversy over the dating of Easter. It’s one in a long line of disagreements about how to interpret Christian lore.

In Northumbria, the politically important swath of land through the middle of Britain that included Melrose and Lindisfarne, the date of Easter was calculated in two ways. The first was Celtic, a tradition that evolved in Ireland and spread across the British Isles. The second was Roman, which evolved in Italy and Gaul. At times, the two dates were as much as 28 days apart.

By the middle of the seventh century, the Northumbrian Paschal controversy, as it was known, had reached crisis point. Easter, after all, with the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, is the seminal event in the Christian calendar. If church authorities couldn’t tell people — including the political and royal classes — when to celebrate that pivotal moment in the calendar, how could they tell them about anything?

Finally, in 664, the Synod of Whitby decided the matter. It sided with Rome.

Lindisfarne had been established by monks in the Irish tradition, and many of them left in a huff after the Whitby decision, returning to their island base of Iona, a Celtic Christian community off the west coast of Britain. Cuthbert was eventually summoned to bring the remaining monks at Lindisfarne into line with Roman teachings. He arrived in the 670s, did the thankless job, causing much bitterness, and then hied it out of the abbey to live as a hermit on first one and then a second smaller island in the sea near Holy Island, visible from Lindisfarne.

His refuge didn’t last. In 685, his sovereign, King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, ordered him back to administrative life, and he became bishop of Lindisfarne. He died two years later, on March 20, 687, having taken refuge once more on his offshore retreat after he became too sick to work. In his final days, alone and mortally ill, he had no food or water save for bites from five onions hidden under his bed.

We know all this about him, and much more, because the Venerable Bede, a Northumbrian monk who died in 735, wrote three accounts of Cuthbert’s life. Bede, whose works I read in Latin as an undergraduate, was a fierce, influential supporter of the Roman church. He was also a savvy propagandist. He saw Cuthbert as the ideal compromise between the Irish and Roman churches. Cuthbert, he believed, had the necessary obedience to Rome’s timekeeping but also the appeal of the Irish aesthete. On the 11th anniversary of Cuthbert’s death, Bede wrote, the monks of Lindisfarne opened Cuthbert’s tomb and found the body undecayed. His clothing was still clean, fresh and bright. It was another miracle.

The cult of Cuddy began. He was sainted. Pilgrims basked at the holy shrine of his power at Lindisfarne. But then in 793, Vikings attacked Lindisfarne. Several years later, fearing more raids, the monks of Lindisfarne took Cuddy’s remains from the island and embarked on a drawn-out quest for a safer resting place. They wandered and took shelter for 120 years along the route that I am on now.

***

The Eildon Hills, the first climb of St. Cuthbert’s Way, looked meek on the maps I consulted at home in Toronto. But here, faced with steps that seem to go on forever, I realize this climb is a brute.

I’m regretting not having trained more in the months leading up to this. Our pilgrimage leader Cheryl Murfin, a writer and photographer from Seattle who has done this route several times, advised a 12-week training regime — on hills — culminating in at least three 16-kilometre treks.

Amelia Williams, a poet and my friend for 45 years, has been steadfastly hiking the Appalachian Trail near her home in Virginia. Melissa Hart is a trail runner from Oregon whom we nickname “the gazelle” for her fearless speed and endurance. Her sister-in-law, Amanda Smith-Hatch, is a horseback rider who has been taking dogs on long hikes through the hills near her home in upstate New York.

I never got close to meeting the training schedule. I invested in new hiking boots and built up to long-ish walks, but mainly on flat city streets. Today, my legs are already feeling the burn, and we’re only partway up the first climb, with about 11 kilometres of trekking still to go.

But then we reach the summit. It’s a glorious panoramic view of the borderlands. Tidy harvested fields. Low stone fences. Sheep off in the distance. The marks of battle are obscured by generations of husbandry.

We wend our way from the lookout into a majestic expanse of woods. These may be some of the oldest trees in Britain.

The air smells clear. The five of us are glowing with exertion and with the joy of being on this journey together. We are all women, all writers, all in our 50s and 60s. For these eight days, we have broken free from our daily routines and from taking care of others in our lives. Instead, we’ve given ourselves over to our own needs and gone wandering into the unknown. It feels subversive.

And exciting, because we are also engaged in an experimental writing course. Murfin is teaching us that walking in nature, combined with making art, such as sculpture, drawing and painting, can unlock our creativity. I’m frankly skeptical. I have made my living as a writer for decades and have found that most of what gets words written is simply sitting and writing them. But I’m also stuck. I’ve been gestating a story — or is it an essay or a memoir or a book? — for two years and haven’t been able to figure out how to get it on the page. I know that part of my pilgrim’s quest is to give birth to whatever it is that I need to tell.

Already, I sense that it’s starting. Last night, on the eve of the trek, Murfin handed each of us a wad of sculpting clay. Any pilgrimage, she told us, involves transformation. You are different at the end than at the beginning. So what vessel are you travelling in?

I held the white clay for a few moments, warming it in my hands. And then I began to fashion a womb, tears streaming down my face. Part of the story I need to write is about my grief that, despite some progress my generation fought hard for, our daughters still do not have the same options as our sons.

In fact, it feels as though backlash against women is mounting across the planet, assisted by alliances between political power structures and hard-right faith systems, those ancient twin forces of subjugation. In North America, we’re in the unceasing era of U.S. President Donald Trump with its constraints on what women can do with our bodies. I’m still outraged about “childless cat ladies,” the unforgettable dis of JD Vance, who went on to become vice-president of the most powerful nation in the world.

These are declarations that our wombs still define us. That bigots seek to squelch our gifts because of them. They want us to creep. My fellow pilgrims and I want to stride.

***

We are more than halfway through our journey, walking between 16 and 19 kilometres a day according to the app on my phone, stopping overnight at St. Boswells, Jedburgh, Morebattle, Kirk Yetholm. I am amazed at how well I’m holding up. I feel stronger each day. My fellow pilgrims call me the pack horse because I just keep going. Maybe not elegant or graceful, but consistent. I’m finding something intensely joyful about keeping going. The holy path is there. I take it. When I get tired, I recite my mantra: walking is healing. I know I’m doing this for a reason.

The woods and fields blur together in my memory and so do the wooden stiles and the swinging bridges and the hills. We are talking so passionately — family, children, writing, books, politics — that we keep missing the trail markers and have to turn back. In a nod to the risks, Murfin has supplied each of us with an electronic tracking tag in case we get separated or lost. This is the end of the pilgrimage season, and we are among the few still out on the trail. If one of us were injured, it would be an ordeal to get to help. We joke about converting our walking poles into stretchers.

We pass crumbled castles, like Cessford, a thick, lidless box of red stone and moss set on a hill among tenderly manicured fields. Only a few kilometres from the English border, it was a brutal strong-hold, site of sieges, in the border wars during the Middle Ages. Now, black-faced sheep graze in its courtyard. We spend part of a day wandering along the River Tweed, delighting in the cobble, and we sit under the luxuriant green boughs of ancient beech trees next to a trickling stream.

We climb and climb, always aiming for the next peak, following the cross of St. Cuthbert. At times, Cuddy’s path merges with Dere Street, built by the Romans nearly 2,000 years ago to aid the military push to the north of Britain. We are walking through this land’s history. I am walking through my own history, too. My father’s father was born a few kilometres from here, near Edinburgh. At times, I catch the sound of my father’s voice in the lilt of the locals. He has been dead for nearly eight years.

I keep thinking about Cuddy. I find myself resistant to his pull. In this moment, I’m sick of cults of personality. I’m impatient with propaganda and weary of machinations between church and state for political gain. I’m struggling to remember that Cuddy was a real person, not just an idea.

I’ve seen photographs of some of the relics buried with him, now on display at Durham Cathedral’s museum. The pectoral cross of rubies and gold that somehow escaped confiscation in the 16th century when King Henry VIII created the Church of England and ordered the dissolution of the monasteries. The portable altar Cuddy used as an itinerant preacher in the 600s. A homely ivory comb with which monks likely tidied his corpse’s hair. And then there’s the oak coffin, decorated and engraved in both Latin and runes, made for his body in 698 and then used to carry him through these hills. It is one of the earliest British cultural artifacts of this nature to have survived.

Most moving of all is the account of the examination of Cuddy’s skeleton in 1898. Canon William Greenwell of Durham and Dr. Selby Plummer, both medically trained, discovered that the saint was about five feet eight inches tall and had buck teeth. Plummer concluded that Cuddy’s face would have shown “considerable character.” Not a natural beauty, then, I assume. In death, Cuddy is all too human.

But if I’m wary of the idolatry of Cuddy, I’m still savouring the metaphor of pilgrimage, feeling like part of a grand tradition. These quests for salvation, for penance, for self-knowledge have fired the imagination of artists for hundreds of years. In the late 14th century, for example, Geoffrey Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales with its themes of rejuvenation and rebirth. Three centuries later, John Bunyan allegorized the struggle with self in The Pilgrim’s Progress.

Pilgrimage is proving to be fertile ground. Words are pouring out of us in the writing workshops we do every day and evening under Murfin’s direction. We are drawing, making collages, painting and then converting thoughts long masked into poetry and prose that we read aloud to the group. I have not made my breakthrough yet, but I am getting closer.

***

I’ve been afraid of this day, the longest of the pilgrimage. We are headed through the Scottish moors into England, trekking at least 20 kilometres. It will take us all day. One knee has already become cranky, and Murfin has loaned me a stretchy cloth brace. But the weather has turned from rainy to gloriously sunny. A rainbow arcs across the landscape. Today we are in the remote hills, far from any villages, face to face with our own limitations.

Just past the border with England, we take a short detour to Eccles Cairn, a pilgrim’s collection of stones on the top of a hill. All we can see in any direction is rolling countryside. Throughout the pilgrimage, we’ve been collecting stones. Murfin hands around pens with instructions to choose one rock, write something on it and then add it to the cairn. It’s a way of shedding burdens. My stone is heart-shaped, flat and pinkish. I write: doubt. And then I leave it behind.

We pause here for a while, silent, lost in thought. This is a sacred place, maybe a place of old magic. It is certainly a place of secrets and dreams. And then we hoist our backpacks once more. We still have a long way to go.

Seven hours in, I’m in serious trouble. Yesterday, I lost my litre-sized travelling bottle and so today I’m sharing Murfin’s stash of water. I’m dehydrated. My calves start cramping. And then my knees burst into agony. By the time Smith-Hatch canters back to check on me, I am trying not to whimper.

She takes charge of my backpack, slinging it across her front, and refuses to leave my side. She’s seen enough of horseflesh to know that either the tendons or the ligaments on the sides of each knee are screaming. Luckily, I have Murfin’s knee brace, and she offers a second one. I put them on and limp along.

Two long hours later, when I catch sight of Wooler, the English town where we’re staying tonight, I can barely walk. I’ve done 24.5 kilometres or nearly 39,000 steps today. I creep into town. So much for my confident strides. There will be no pilgrimage for me tomorrow.

***

The next morning, Williams and I wave goodbye to the other three as they rejoin St. Cuthbert’s Way. We settle into a cozy café and order tea biscuits. This is almost unimaginable pampering after the winds of the moors. Later, we go by taxi to Lowick, where we’ll be staying for the night.

This is our last stop before we reach Holy Island tomorrow, our final destination. I’ve been reading about how the island came to be. It’s the tale of volcanic magma violently thrusting its way through the crust’s limestone and sandstone about 300 million years ago. The molten mass deformed the rock layers and now, cooled into dolerite, lies mostly hidden below part of northern Britain. Holy Island, cut off by tides twice daily from the mainland, is one of the few bits that remain in sight.

So I pose myself the question: how did I come to be here? And that is when the story I’ve been trying to write bursts through. I’m filling page after page. It’s not perfect, but it’s a start.

Later that evening when I read it to the pilgrims, I choke up. Yes, the world has become uglier. Yes, equality is under attack. But my task, I see clearly now, is not only to name the ugliness, but to find the beauty there too.

***

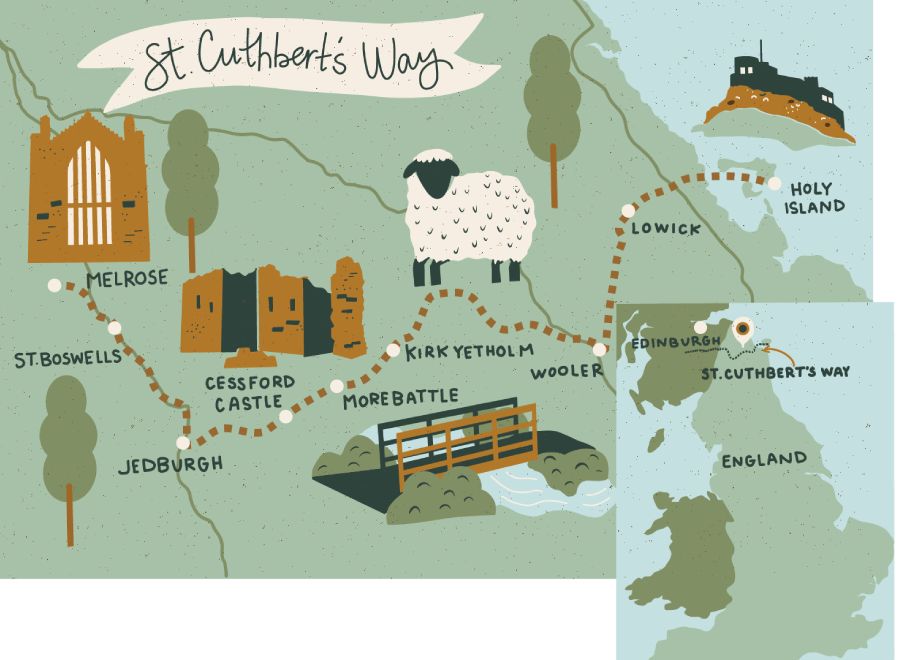

We are at the ocean, getting ready to cross to Holy Island. The first way is along a paved causeway nearly five kilometres long. It is submerged during high tide and clear during low. Second is the pilgrim’s way, a path of a similar length that strikes off from the causeway and runs across the sand flats toward the island. It’s marked by tall wooden poles and is typically walked barefoot. Like the causeway, it is passable twice a day during low tide.

The tide is receding. The air temperature is near freezing, and the wind is high enough to form whitecaps. We are keen to shed our boots and take the pilgrim’s way across the sand. It seems fitting. I have bound both knees in high-strength lidocaine patches and fixed them with the braces. I am ambulatory, but only just.

The tide still seems too high. This enterprise needs careful judgment. Between 10 and 20 cars get stranded and submerged on the causeway each year. People have died here.

Murfin suggests walking the causeway. But we hold out hope, waiting for the tide to ebb. Finally, she offers to test the waters and reaches the line of pilgrim poles. Gleefully, we follow.

I feel like a child. Free. Joyful. Sand squishing through my toes. Brilliant sun on my face. It’s as if every burden I’ve ever carried has fallen away. I don’t remember ever feeling this carefree in my life.

Murfin has gone far ahead. The four of us are alone on the sandy path save for two men much farther back who are also attempting to cross. We can’t stop marvelling that we’ve made it this far. We pass through a stretch of slick mud, sinking to mid-calf, whooping like preschoolers.

In the distance we see Murfin, up to her knees in water. She waves at us to go back and texts us to go to the causeway. Then she disappears. We stand in shock, wet, cold, uncertain what to do. Is she dead or alive? The wind is even stronger now. It’s too dangerous to go forward. We are too cold to go back, and it feels too far. Although we’ve been sternly warned not to cross the unstable sands that lead up to the causeway, we clamber up anyway.

A police officer is there. The coast guard is on its way. An ambulance is racing toward us from Berwick, the nearest town. We say we don’t know where Murfin is. He jumps in his car and speeds along the causeway. The ambulance passes us, wailing. We see it stop near the police car on the island. I’m waiting to see a stretcher and a corpse.

Then the officer comes back. Murfin was swept away and submerged. When she surfaced, she called the emergency service with a phone that was miraculously undamaged. Then she found her way to shore, holding on to the poles. She’s stunned and very cold, but she’s going to be fine. We sag in relief. The coast guard offers to drive us the last couple of kilometres to our hotel. Smith-Hatch and Hart are determined to walk along the causeway. Williams and I look at each other for a nanosecond and then acquiesce. And so the final stretch of my pilgrimage ends in ignominy in a coast guard hatchback.

***

We have been wandering the island since the rescue, reading a newspaper account of it, trying to make sense of this odd ending. It’s Sunday morning, so I decide to go to a service at St. Mary’s, the medieval parish church standing next to the bones of a 12th-century priory built to honour Cuthbert. A massive statue of him stands in its ruins.

Inside St. Mary’s, islanders are gathering. Behind me, at the back of the sanctuary, stands a life-sized elmwood sculpture depicting six monks in medieval robes carrying Cuddy’s coffin to Durham. Placards along the walls tell Cuddy’s story. On one stone wall hangs a gold-framed, hand-inked list of church officials linking the first bishop, Aidan, appointed in 635, to Cuthbert in 685, all the way to the current vicar, Sarah Hills, who arrived in 2019.

This morning, Rev. Sam Quilty mentions Cuddy in her sermon. And as I return from taking communion, I look up at a window memorializing Cuddy’s humble life in stained glass. It is beautiful. Cuddy is alive here. He matters to these people. And, now, to me. He is part of the bones and history of our faith, one of an unbroken line of generations of believers who have helped our church evolve. He is not just the name on a pilgrim’s path or a hagiographer’s invention.

Maybe this, too, is part of the transformation I was seeking: the simple faith that storytelling has its own power and can endure.

***

Alanna Mitchell is a journalist, author and playwright and the features editor at Broadview. She lives in Toronto.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s March 2025 issue with the title “On the trail of St. Cuthbert.”