At the very start of Pick a Colour, the narrator Ning tells the reader how it feels to give manicures and pedicures all day. “Looking at the two of us, them sitting on a chair above me, and me down low, you’d think I am not in charge,” Ning says. “But I am.”

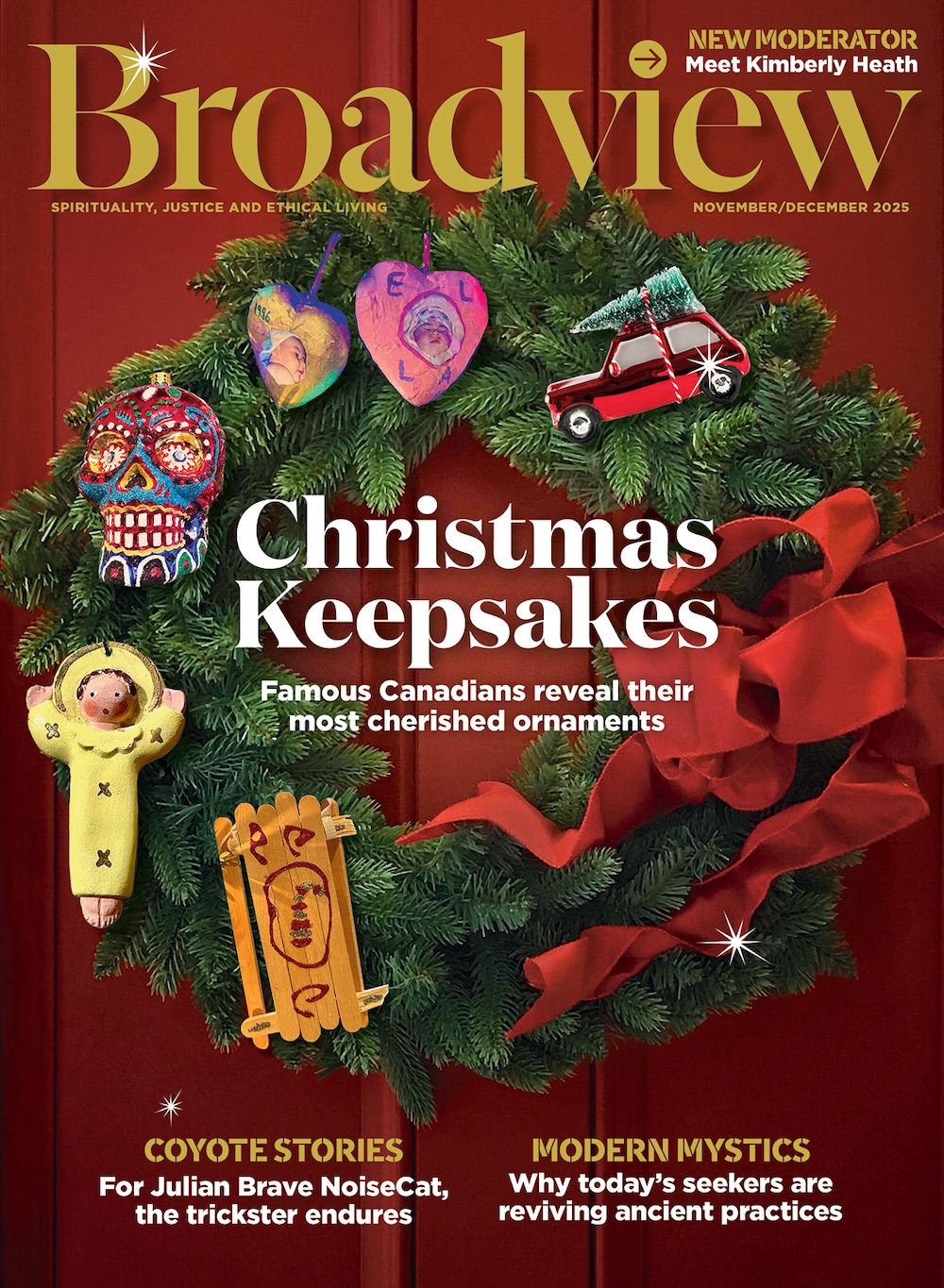

Souvankham Thammavongsa’s Pick a Colour follows Ning and the women she employs through a single day in her nail and beauty salon. Shortlisted for this year’s Giller Prize, the novel is Thammavongsa’s first, and it comes after her Giller-winning collection of short stories, How to Pronounce Knife, as well as several poetry books. It is quiet, observational and stunning.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In Pick a Colour, power is complicated. When clients take a seat in the salon’s cushioned chairs, they unload their life stories without a second thought to the women filing their nails or threading their eyebrows. As female service workers and especially as Southeast Asian immigrants, Ning and her employees are often misunderstood by clients — seen as incompetent, or hardly seen at all.

More on Broadview:

- Leah Gazan on why Canada should outlaw residential school denialism

- Chicago pastor says an ICE officer grabbed his throat during peaceful protest

- Ontario’s new recycling rules are creating a hidden crisis for non-profits

In one telling moment, the staff reflect on a white woman Ning used to employ at the salon. “Everyone thought she owned the place,” one of them recalls. “She gets to have that without having to do anything. The sight of her alone supposes she’s boss.”

Though clients view Ning as subordinate, she inverts this dynamic by locating power in listening and knowing. She also mocks and imitates whoever is in her chair, joking with her employees in the language they all share so her clients can’t understand. And she’s confident that, once she has a client, she never loses them. “We get them all back,” she says. “You just tell them ‘ten dollars.’” In all of these ways, Ning claims the upper hand.

For Ning, a former boxer, a lot of day-to-day interactions feel like they’re happening in the ring. The awareness of power, the defensive postures, the unexpected blows, the drive to claim a victory. And yet, there are moments when her fists come down and her gloves come off — when she scoops a dead bird off the streetcar tracks, when she offers a free salon appointment to a man who needs it, when she listens to a client vent and thinks, “I want to make things better for her. Give her hope.” These glimpses of genuine human connection give the novel its soul.

“I hate to say this now, but you know most people are not all that interesting,” Ning tells us at the start of the novel. But Ning is the sort of first-person narrator whose truth lies between the lines, even as she begs you to take her at her word. It quickly becomes clear that she finds people fascinating and their stories worthwhile. She sees them, even when she tries not to, and she longs for them to see her. She can’t help it. It’s what makes her — what makes all of us — human.

***

Amarah Hasham-Steele is a journalist in Toronto.