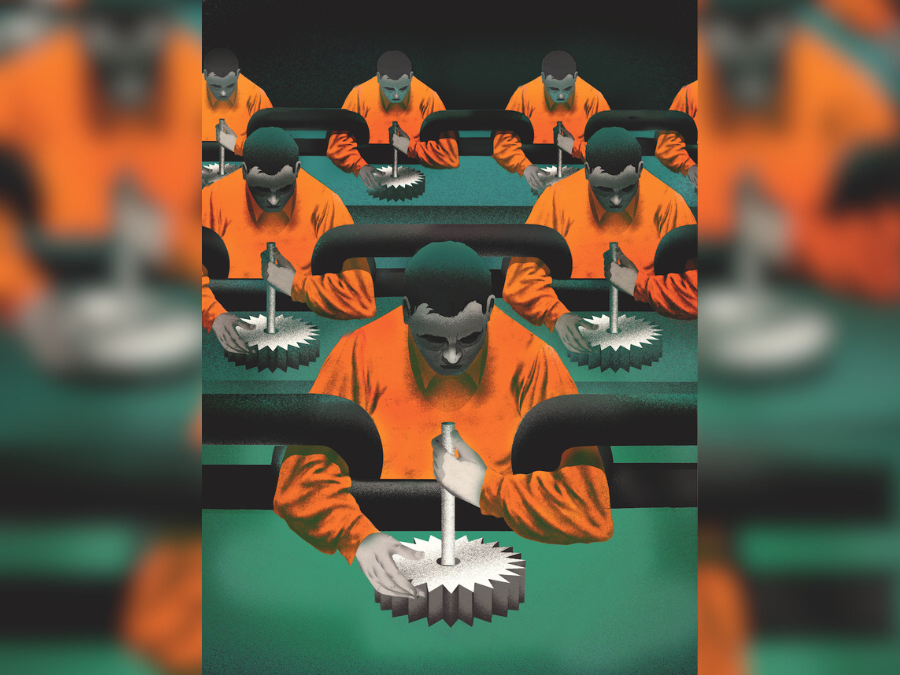

Across the country, a vast hidden workforce of people spend their days doing clerical work, cleaning, landscaping and other tasks that keep institutions running. Others, working in factory-like settings, build furniture for federal government offices and refurbish military vehicles. Some clean barns and milk cows. Still others maintain and inspect firefighting equipment during wildfire season. Their work has generated profit across multiple lines of business. And yet, their take-home pay is capped at $6.90 a day, far worse than it was decades ago. They can’t unionize. Demanding better pay and working conditions is out of the question. They’re punished if they refuse work. And they can’t walk away from a bad job or even a dangerous one.

Who are they? Inmates in Canadian prisons. They are part of a global phenomenon of prisoners’ labour that reaches into cupboards and fridges with products such as breakfast cereal and soft drinks. Officially, Canada has banned the importation of products produced by prison labour in other countries. Yet in Ontario, inmates’ labour produces milk that supplies the provincial dairy quota. During the pandemic, inmates’ labour created personal protective equipment that kept government workers safe. It even contributes to our national security through refurbishing military vehicles for Canada’s Department of National Defence (DND).

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Prisoners work because, in theory, it helps them gain practical and marketable life skills for their release. Both Canadian law and correctional policy state that prisoners don’t work as punishment but as a part of their rehabilitation. Prisoners also work to help cover the cost of their incarceration.

Critics say the prison work system is brutally flawed and ineffective. Many aspects of prison labour fit the definition of modern slavery, an umbrella term for situations that exploited people are unable to escape because of threats, violence, coercion or the abuse of power, such as forced labour. As a result, a multi-pronged movement is emerging in Canada to start unions and advocate for better pay and working conditions for inmates. But if the prison workforce itself is so poorly known, how can we assess the efforts to hold the system to a higher ethical standard?

***

In Canada, there are two types of prison work. The first and most common involves maintaining the daily operations of the institutions — tasks like cooking, cleaning, laundry and administrative work. That labour, in effect, subsidizes the operating costs of the institutions, write Jordan House, professor of labour studies at Brock University in Ontario, and lawyer Asaf Rashid in their 2022 book, Solidarity Beyond Bars: Unionizing Prison Labour.

Then there’s the business side of prison labour. CORCAN, an agency within Correctional Service Canada, offers conditional employment programs to some people in federal prisons. These programs produce goods and services sold to and used by other government departments and agencies. CORCAN is the largest prison industry operation in the country, with 103 workshops in 36 of 53 federal institutions across Canada. Its business lines include textiles, manufacturing, construction, services, agriculture and some Indigenous crafts. In the federal system, the majority of the approximately 12,000 prisoners (as of 2023) work either for CORCAN or to maintain their institutions. Prison industries also exist at the provincial level, though there is little information on how many inmates are involved.

No matter what type of work federal prisoners do during their sentence, the maximum they can earn is $6.90 a day before deductions. That’s less than in 1981, when they could earn as much at $7.55 a day, which would come to about $25.47 in today’s dollars. Most earn less than the cap. By contrast, provincial and territorial minimum wages for non-incarcerated workers range from $15 to $19 an hour.

This is not just a Canadian phenomenon. Low-paid or unpaid prison labour is widespread around the globe. A recent two-year investigation by the Associated Press linked global prison labour to the supply chains of hundreds of food brands, including Frosted Flakes cereal and Coca-Cola. In Finland, which is home to a rapidly growing tech ecosystem, prisoners are employed as low-paid “click workers” training artificial intelligence. The United States has increasingly deployed prisoners to respond to environmental disasters such as fires and floods. Early this year, nearly 950 California inmates who fought the Los Angeles fires alongside non-incarcerated fire crew earned at least $328 less than their counterparts each day for equally dangerous work, write House and Lydia Dobson in The Conversation.

Canadian inmates also have to pay some costs for food, accommodation, the administration of the phone system, an inmate welfare fund and a savings plan for after they get out. Once those mandatory deductions come off, the day’s pay typically drops to $2.78.

Most of what’s left goes toward buying food in the canteen, says Ivan Zinger, who is the Correctional Investigator of Canada, a position established in 1973 by Parliament to act as an independent ombudsman for people in the federal corrections system. Both the quality and quantity of prison food has deteriorated since the government of then prime minister Stephen Harper brought in austerity measures in 2014. The canteen, once a destination for snack foods, now resembles a small grocery store stocking food like potatoes, chicken and tuna that inmates either use from tins or cook in microwaves or kitchens.

“Whatever they’re [earning] is all destined to complement their diet,” Zinger says. He has written that the payment system is “so fundamentally flawed that it fails to substantively meet its primary legislative and policy objective, which is to encourage participation in programs, vocational and work opportunities behind bars.”

Low pay also fosters an underground economy in prisons where abuse, bullying, extortion and other forms of violence become prevalent. It prevents people from saving up for their release or helping to support their families on the outside, setting them up to fail. And it gives prisoners the wrong idea about work, says Sena Hussain, communication and resource development co-ordinator at PASAN, an organization based in Toronto that supports people who have been through the prison system and others who are affected by the justice system.

“When they’re in prison and they’re doing work like this, where it’s hard labour and they’re only making $6 a day, what’s the message that that’s sending them?” Hussain asks. “It just confirms to them that this is not a good way to get ahead in life.” If anything, she says, it reinforces the message some went in with, which is that to make it out of poverty, they need to keep doing the kinds of illegal activities they did to make money before they were arrested.

“If you don’t work, you’re punished, and you can be made to work as punishment.”

Canadian prisoners used to be able to earn more. At one time, not only was the daily rate higher and the food better, but mandatory expenses were lower and workers could earn incentive pay. Vic Toews, minister of public safety in Harper’s government, announced in 2012 that he was eliminating incentive pay at the same time he announced that inmates would have to pay more for room and board and phone usage.

Kevin Hale (not his real name), who is nearing the end of a life sentence and is up for parole, says he once earned about $800 every two weeks, including his incentive pay.

“Well, if you saw what we had to do to make that money….There are some of us that have actual tickets [skilled trade certifications], like as machine operators and as wood carpenters…and we’re working from 7 o’clock in the morning until 4:30 at night,” he says. “We’re actually putting in a full day’s work.”

And sometimes more. Hale would often keep working until 9:30 p.m. and work on weekends. Sometimes he’d clock close to 30 hours of overtime a week.

Low pay is only part of what he has experienced in prison. At Warkworth Institution, a medium-security prison near Campbellford, Ont., he worked in the massive “DND shop” refurbishing Canadian military vehicles. Vehicles arrive at the shop with certain parts painted yellow, indicating they need to be replaced.

“My job was to pull the engines, rebuild them, put them back in, sandblast it, repaint the truck and put new plate numbers on,” he says.

The specialized paint he worked with is hazardous to human health both during the painting and drying process and when it’s being sanded or welded. When Hale refused to work because he needed better protective equipment, he was locked in his cell on “off privileges” and threatened with being fired or shipped to another institution. He says the issue was resolved after his bosses consulted with industry experts on the outside and realized they could be liable if they didn’t give him the standard safety gear for the job.

The case can be made that forced labour exists in Canadian prisons because the kind of situation Hale experienced is common, says House. In many provinces and territories, legislation says that people who are incarcerated must work, he notes. Failure to do so violates prison rules and regulations, and there are punishments for work refusal, including additional work.

This is a direct form of coercion, House says. “If you don’t work, you’re punished, and you can be made to work as punishment.”

But there are also more roundabout ways of coercing prisoners to work in both the provincial and federal systems, he says. One of these is the need to prove good behaviour and to have a good record of performance — including work performance — to get parole.

“In this way, poor work performance can result in people spending more time in prison, because if they can’t prove to a parole board that they’ve been a good worker, this could be a strike against them and basically extend their sentence longer than it might be otherwise,” House explains.

***

Prison work sometimes does lead to success back in the community. Take Spencer St. Amand. The first time he arrived at Grand Valley Institution in Kitchener, Ont., he wasn’t interested in a work program. “I was sentenced to time, not labour,” he says, recalling his initial attitude. But when he found himself at the institution a second time in 2023 on similar drug-related convictions, he decided to make it an opportunity to gain work skills.

It took knowing the system, plus skilled negotiation. Like other prisoners, he had a correctional team that included a manager, a staff guard and a parole officer. He had to build a rapport with them and convince them he wanted to be successful. “Since their mandate is to reduce recidivism, and given my history, I just pushed that this is a perfect opportunity to be able to make this happen. So what can we do together?” he says of his changed outlook. “I can put in the work and the effort, but I need my team to do their end to be able to make the stuff happen.”

He was able to apply to a six-week construction techniques course in which outside carpenters came in to help participants build a gazebo for the property. Then he applied to work in the CORCAN construction program making items such as chairs and picnic tables. Eventually, he became one of the first people at the institution to start a carpentry apprenticeship.

“I did not bust my butt every day for money,” he says, chuckling. “I busted it to learn new skills so that I could actually do something different upon my release….Changing that mindset is what made me get up every morning and go out there, whether it was freezing cold or scorching hot.”

Now on a work release using his new skills to refinish furniture, St. Amand says until his Broadview interview he hadn’t thought of the work he did at Grand Valley in terms of modern slavery because he came out of it with a vocation.

“On the other hand, when they start marketing and capitalizing off our work, well, maybe that is slavery because we are getting minuscule pay,” he says. “There is somebody capitalizing off of that.”

St. Amand is the exception, not the norm, Zinger says. In 2023-24, federal prisoners earned 22,463 vocational training certificates, a jump of 35 percent from the year before. But 80 percent of prisoners’ work is tied to the menial labour they do for their institutions, which doesn’t translate to outside employment because it is low or unskilled work. CORCAN jobs are only available to about seven to eight percent of the federal prison population. Worse, the vast majority of CORCAN jobs involve making textiles such as low-quality garments or sheets, skills not transferable to the Canadian labour market because Canada imports most such textiles from Southeast Asia or China.

***

What would it take to make the prison labour system more ethical? Some countries give prisoners training that better prepares them for the actual labour demands of the economy they will be emerging into. For the past 30 years in Italy and Sweden, prisoners have been able to form and participate in co-operatives. One example is Cooperativa Alice in Milan, where incarcerated people and at-risk women learn the kinds of couture skills required by the luxury fashion industry. Catherine Latimer, executive director of the John Howard Society of Canada since 2011, is “very keen” on Canadian prisoners having similar opportunities.

More progressive approaches to pay are also cropping up in other jurisdictions. In 2023, German prison wages, which ranged from €1.37 to €2.30 ($2.15 to $3.60) an hour, were deemed too low by the country’s Federal Constitutional Court, which noted institutions ought to provide working prisoners a meaningful benefit over those who opt out of working. Both Norway and Sweden offer pay based on market rates, or close to them. And in New York State, a prison minimum wage act that aims to set the minimum wage for prison work at $3 per hour is under consideration.

In Canada, some simple, immediate steps would go a long way toward making the system better. One is to improve prisoners’ purchasing power by, for example, making some items — soap, shampoo and over-the-counter drugs like Tylenol — free and removing certain mandatory deductions like those for cable television and telephone.

“That would improve [the situation] quite a bit without going back to the Treasury Board or the Finance Department to get more money,” says Zinger. “It would be easy to do.”

Adjusting the programming could also help. At the moment, while some good jobs in the CORCAN system provide vocational training opportunities, those jobs often don’t go to the people who need them the most, Zinger says. Instead, they go to people who already have good work ethics, are trying to spend their time in prison more constructively or prefer working over having nothing to do. Programs that provide new vocational skills and address mental health issues and substance use would be valuable, he says.

“You’ve got an opportunity while they are in prison to provide programming that would help them improve their chances of becoming law-abiding,” Zinger says. “If you reward them and they see that they can get ahead while in prison, with some sort of pay system that provides incentives for behaving properly, the system will do far better and be more effective at releasing individuals who are less likely to reoffend.”

In the longer term, the levels of pay must be revised and incentive pay reintroduced, he says. People could then save money while in prison and use it to have a better chance of reintegrating into society.

A more structural fix would be to make sure prisoners are protected by the same laws and regulations that cover workers outside prison, including the right to unionize, House and Rashid argue. That means formally recasting prison work as employment rather than rehabilitation. It also means allowing prisoners to be classified as employees. At the moment, prisoners are excluded from employee status under federal and provincial legislation. To succeed, such a strategy would need support from the broader Canadian labour movement.

Jeff Ewert, president of the Canadian Prisoners’ Labour ConFederation, has already begun a charter challenge to get federal prison workers unionized, claiming that excluding prisoners from the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act violates their constitutional right to freedom of association.

In an April interview with CKUT, a community radio station based at McGill University in Montreal, Ewert explained that it wasn’t just what happens at work in prison that made him want to start a prisoners’ union.

“It’s everything to do with prison,” he says. “Because prisoners live where we work, absolutely everything that we do is labour related. For example, you’re sleeping, and a guard shines a halogen flashlight in your face at 1 o’clock in the morning and wakes you up. Now you’re tired, and you go to work around a very dangerous pneumatic press that doesn’t have proper safety features and lose a piece of your finger.”

Precedent for prison workers’ unionization exists in Canada. In 1977, prisoners who worked at the commercial abattoir at the now-defunct, provincially run Guelph Correctional Centre in Ontario successfully unionized with co-workers who weren’t incarcerated, achieving equalized wages, among other rights.

But giving prisoners more rights can be a hard sell, especially when politicians want to crack down on crime and when prison labour is so invisible in the first place. Some Canadians see any gains made by prisoners as a loss for victims and the public, House and Rashid write, despite the fact that prison sentences don’t undo harm to victims or make restitution.

More on Broadview:

- Proposed prison has turned these rural residents and abolitionists into allies

- Tent cities are growing in Canada — so is the call for meaningful change

- Why child poverty is rising in Canada again

While few Canadians actively lobby for prisoners’ labour to be exploited, some are firmly opposed to any attempts to improve the lot of inmates. “There is something negative in a certain segment of society that thinks that once you committed a crime and are sent to prison that you should suffer and you should have no benefits whatsoever,” Zinger says.

And what about those whose lives have been devastated by criminal acts? Intriguingly, victims and victims’ rights organizations are among the strongest voices in favour of less punitive forms of sentencing, including sentencing circles and restorative justice, write House and Rashid. Better treatment of prisoners and more supports can forestall future crime and therefore enhance public safety, such organizations argue.

That’s why Zinger says another piece of crafting a fairer prison work system requires educating the public about the risks of a “tough on crime” political agenda. Programming that doesn’t punish but allows people to develop skills, get treatment and have access to resources and a social safety net means they can survive without turning to crime when they are released, House says. Simply put, research shows that treating prisoners humanely is key to keeping them from reoffending.

***

This article first appeared in Broadview’s September/October 2025 issue with the title “Sentenced to Labour.”

Leslie Sinclair is a journalist in Toronto.