Kyle Tomlin grew up on a steady diet of comic books in 1970s and ’80s New Jersey: Batman, Indiana Jones and Spider-Man. Sundays after church, he and his brother would hurry to the local newsagent to buy them, “a highlight of my life back then,” Tomlin recalls. He saw himself in the characters. “Because Peter Parker was bookish and nerdy, which was me as well, I felt like I understood him and could easily see myself being him. I felt an emotional connection to him and his world.”

That feeling never diminished. For the past 40 years, Tomlin, now an Episcopal priest serving the Church of the Messiah in Fredericksburg, Va., has kept up this comic book habit. In fact, he and two priest buddies record regular episodes of God and Comics, a podcast exploring the deep theological themes in secular comics. For example, two episodes in March 2018 — on Black Panther and the civil rights movement in comics — lay plain the Christian call to stand with the oppressed.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

As a priest, Tomlin says, “I’ve come to see over time that comics accurately portray the human condition. That is, they tend to have their finger on the fact that people are looking for some form of hope and rescue….We are all sinful people, as the scriptures say, who are desperately trying to control not only our own lives, but the lives of others. In essence, we desire to be like God. I think that picture gets painted in the stories comics often have to offer, and it becomes a good launching point to talk with people about the Christian faith.”

So, you’d think that a children’s Bible in the form of a comic would be a hit with the younger Tomlin. He remembers being given Great Adventures from the Bible, released by Chariot Family Publishing in 1984. “Exciting picture strips bring the Bible to life!” the cover promised. For Tomlin, though, Great Adventures fell flat. Despite going to church regularly and even being interested in deepening his faith, he felt the book seemed too forced, too “churchy.” There’s a difference, it turns out, between a child-friendly format (a Bible in comic book form) and a child-pleasing allegory (Peter Parker’s quest for justice despite his low social status). “I think we find ourselves more attracted to darker places,” says Tomlin. “That’s not a bad thing. We have to know ourselves before we can really hear the Gospel.”

The merging of comics and the Bible is nothing new. Since the 1940s, Christian publishers have pumped out Bible stories as pulp comics complete with bold visuals and non-stop action. Strategically, it’s a no-brainer. Similar to Christian apps and websites today, the medium is the message: the comic book Bible tries to make scripture palatable and relevant for kids.

Even among children’s Bibles that are not comic strips, the masterful formula of narrative scripture and illustration continues to be North America’s unlikeliest publishing success story. Despite decades of plummeting Sunday school attendance, some children’s Bibles sell millions of copies. Dozens of new titles hit stores every year. People are buying these things. But are children’s Bibles actually inspiring new generations to have a deep faith? Or are they just well-meaning gifts from grandparents that collect dust on kids’ bookshelves?

As a genre, children’s Bibles are usually paraphrases of biblical stories — condensed, curated and often overtly explained. The first known children’s Bible was Historia Scholastica, an illustrated manuscript created in 1170 for university students by Petrus Comestar, according to Ruth Bottigheimer, author of The Bible for Children: From the Age of Gutenberg to the Present. Comestar’s text presented selected biblical stories in Medieval Latin and became popular with children. It was translated into many languages and stayed in common use until the late 1300s.

More on Broadview: How faith inspired many of our favourite superheroes

With the rise of the printing press, children’s Bible publishing boomed across Europe. Bottigheimer, a professor of children’s literature, identifies several volumes crucial to the development of the genre. Histoire du Vieux et du Nouveau Testament (1670), for example, was the dominant Catholic children’s Bible for nearly two centuries. Biblische Geschichten (1832) was another influencer “because it furnished the text that international Bible societies most often translated into scores of exotic languages for proselytizing throughout the non-Christian world,” writes Bottigheimer.

Fast-forward to the middle of the 20th century, and children’s Bible publishing was a thriving industry in North America. When you think of a vintage children’s Bible, you may picture the not-so-creatively named The Children’s Bible. This iconic 1965 brown-and-purple juggernaut was published by Golden Press, which is part of the same parent company as the massively successful Little Golden Books and Gold Key comics. But The Children’s Bible is just one of hundreds published over the past six decades, with a goal to get scripture into the hands and hearts of generations of kids.

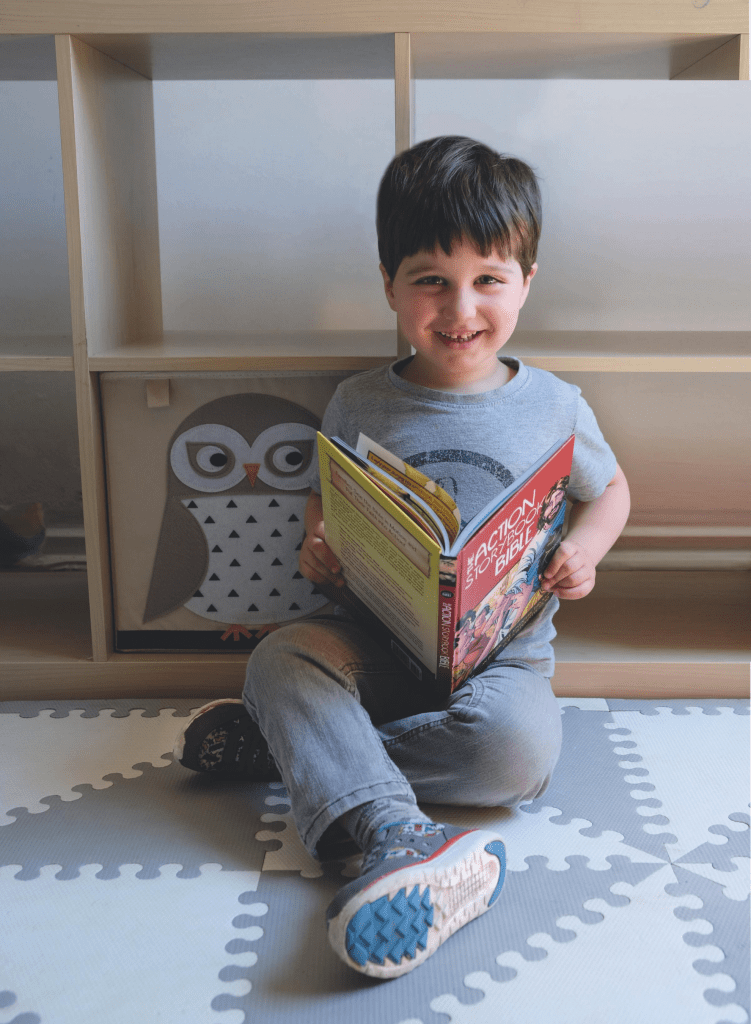

That urge to draw children’s eyes to the Testaments is just as strong today. The stakes are even higher than in 1965, given that the vast majority of culturally Christian families no longer spend Sunday mornings in a pew. With this in mind, about 15 years ago, the publisher David C. Cook gathered a team to produce a new comic-style Bible with graphics suited for 21st-century preteens to replace its 1978 edition of The Picture Bible. The coup d’état was securing Marvel and DC Comics illustrator Sergio Cariello to create the artwork for the 752-page book. Cariello, a graduate of both Bible school and art school, has drawn Wonder Woman, Green Lantern and many other works for major studios. The result was The Action Bible, which was published in 2010 and has since sold more than 1.5 million copies worldwide, as well as a vast range of supporting products: a study Bible, Sunday school curricula, figurines, a colouring book and even a set of 54 trading cards similar to Magic: The Gathering and Pokémon. The appetite for The Action Bible, available in 31 languages, seems limitless.

“We ask families what they need, and there’s that tension of not wanting to have too much time in front of screens, but wanting to meet kids where they are,” says the publisher’s content developer Stephanie Bennett. She notes that The Action Bible has also had rave reviews from people behind bars and is especially beloved by children with autism spectrum disorder and learning disabilities. “We really take the stewardship of this Bible seriously.”

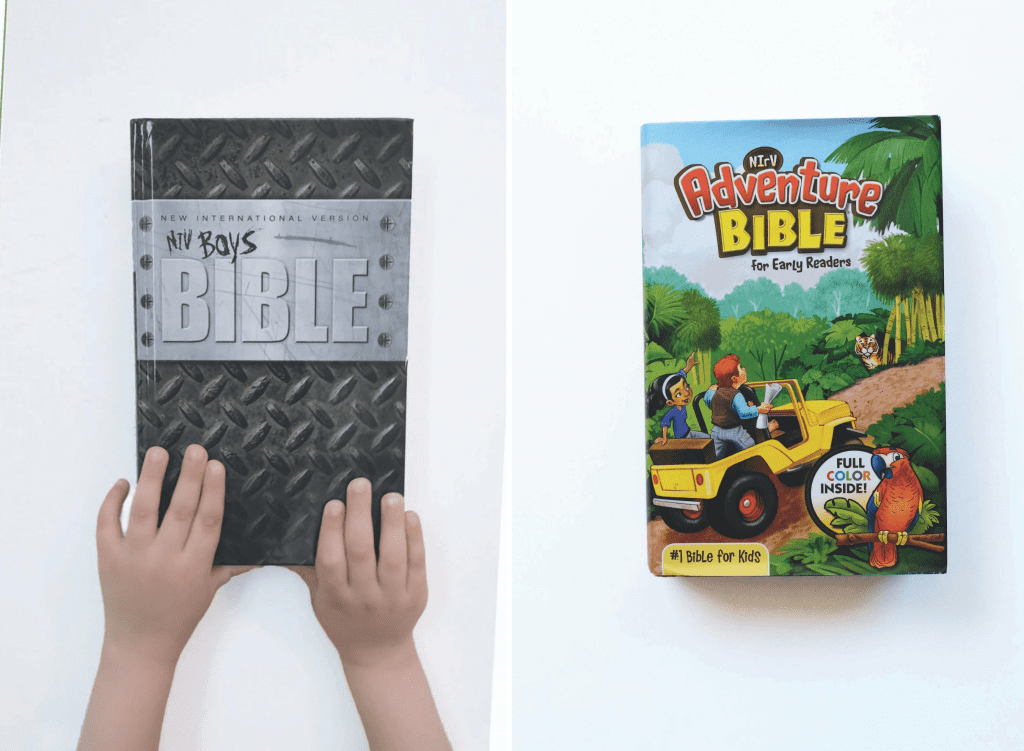

One company that overshadows Cook’s Action Bible empire is HarperCollins, Rupert Murdoch’s conglomerate, which acquired Christian publishers Zondervan and Thomas Nelson. Zonderkidz’ The Adventure Bible brand is among the publisher’s biggest sellers. It’s a New International Version study Bible, offering a true translation of scripture rather than paraphrase, plus blurbs and graphics to help children grasp the historical and cultural context.

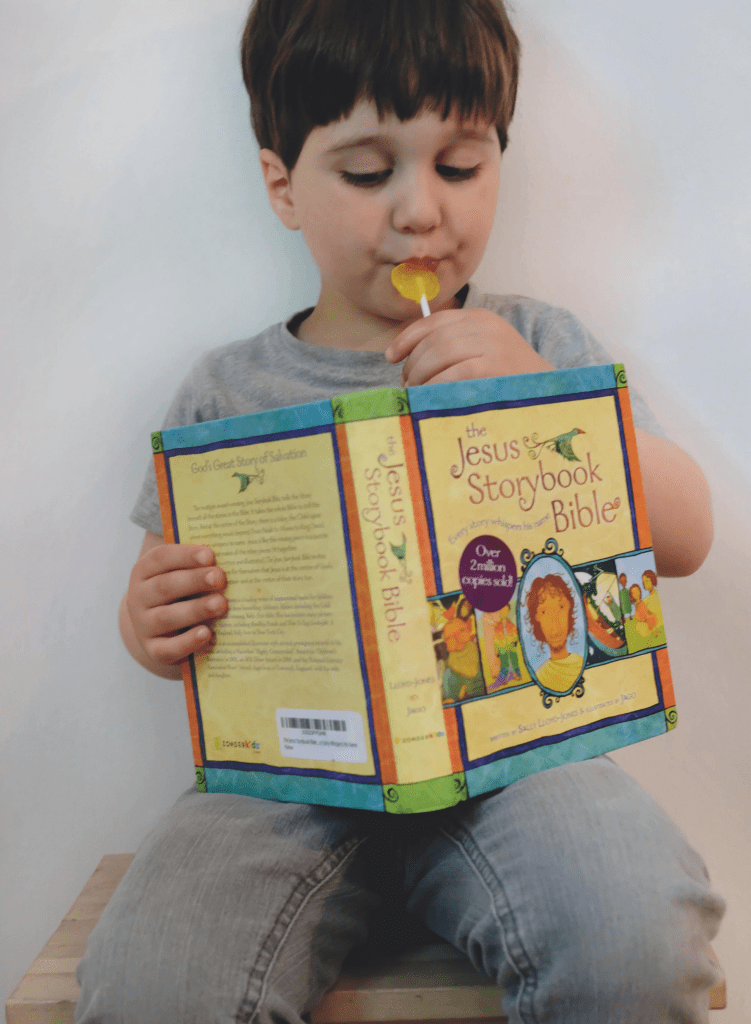

With over two million sold in more than 30 languages, Sally Lloyd-Jones’ The Jesus Storybook Bible: Every Story Whispers His Name (2007) is another Zonderkidz bestseller. Jago Silver illustrated the book’s 21 Old Testament and 23 New Testament stories in his studio in North Cornwall, U.K. He is not religious and had not illustrated faith-based books before, but he couldn’t pass up this project. “I immediately accepted,” he says. “Most picture books are only 14 to 20 illustrations, but this was 180, which meant that I would be in work for almost a year.”

Silver worked with Zonderkidz’ art director to make the characters and locations look authentically Middle Eastern. You’d think this wouldn’t be a shift, as the Bible takes place in the Middle East, but it’s a departure from the all-white cast in centuries of European and North American children’s Bibles. The result is a glorious children’s Bible full of expression and movement, with gentle-faced humans and animals, clearly placed in their original context. Similarly, The Tiny Truths Illustrated Bible (Zonderkidz, 2019) and the recently released Tiny Truths Wonder and Wisdom feature mostly brown people. The creators, Tim Penner and Joanna Rivard, have been working together for eight years. “We found a lot of Bible storybooks featuring a pretty, pink-cheeked, fair-skinned Jesus, and we wanted to fix that,” says Penner.

Sometimes, however, the shift in children’s Bibles is polemic. In Kelowna, B.C., Wood Lake Publishing has issued Ralph Milton’s The Family Story Bible in various forms since 1992. It’s possibly the world’s first inclusive-language children’s Bible, meaning that God is not given gendered pronouns. Unlike most children’s Bibles of the time, it includes stories not considered appropriate for children, such as David and Bathsheeba, which features nudity, adultery and murder.

Milton also went beyond paraphrasing scripture; he added to it. “Ralph is not shy about filling in the gaps,” says Mike Schwartzentruber, president at Wood Lake. “A lot of his stories are imaginative retellings as opposed to recordings. He got some flak from that.”

The Family Story Bible was a blockbuster, but by 2015, sales had slowed. So staff approached Laura Alary, a Toronto–based children’s author, librarian and Christian education co-ordinator for Guildwood Community Presbyterian Church, to create a new children’s Bible. With a PhD in New Testament studies, Alary brought care to paraphrasing and interpreting Bible stories for children. Together with illustrator Ann Sheng, she produced in 2018 Read, Wonder, Listen: Stories from the Bible for Young Readers. “I know I’m not alone in looking for children’s Bibles that are in line with my own progressive theology, that are intentionally inclusive and treat the stories with respect,” Alary says.

In her introduction, she summarizes high-level biblical interpretation and invites children to approach scripture in a sophisticated way. “The fact that people in the Bible disagree about things tells us that we can still be the people of God even if we do not think the same way about everything,” she writes. “What matters is learning to ask good questions, to listen carefully, to think deeply, and — as Jesus taught and showed us — to love one another.”

Like Milton, Alary didn’t shy away from the difficult stories of the Old Testament. She demands valuable engagement from her readers by reframing difficult themes, such as conquest narratives. “I spent weeks pondering what to do with these stories,” Alary says. “In light of what’s happened in our own nation, we’ve got to ask questions about how we’re reading those texts. So I break in as narrator and ask, ‘Did Joshua ever wonder about the people whose homes and walls they were breaking? They were carrying the 10 rules with them. Did it ever dawn on them that there was an inconsistency there?’”

Progressive, inclusive, representative and engaging: the children’s Bibles of the 21st century are unlike their earlier peers. But as with children’s literature in every era, they play an essential role that we need to pay attention to, observes Rick Gooding. The University of British Columbia’s chair of the master of arts program in children’s literature says, “My impression is that when kids are given Bibles, they’re often given as a kind of rear-guard moral action. The idea is that the Bible will offer a kind of moral stability that is lacking in other texts children are encountering. It’s almost invariably religious people that give Bibles, and frequently they’re grandparents. The agenda of children’s literature has always been to socialize the young.”

Gooding is enthusiastic about allegorical young adult literature and how it can help youth navigate political and moral issues. He wonders, though, if the secular press is doing a better job of leading young people into those crucial “darker places,” as God and Comics podcaster Kyle Tomlin put it. Dystopian fiction, such as The Hunger Games (2008) and Feed (2002), “allows the reader to identify with a protagonist who is a rebel — standing up to a widespread injustice,” Gooding says. More recent popular themes include technology and animal rights.

“I wonder if children’s Bibles do too much of telling children what to think instead of drawing them in.”

Rachel Wilkowski

He points out that children’s Bibles, on the other hand, largely avoid thornier subjects. “The whitewashing of biblical stories stems from anxiety about exposing kids to too much violence and sex,” says Gooding. “God seems milquetoast in kid’s Bibles.”

Children’s Bible scholar Ruth Bottigheimer takes the analysis a step further when she points out that scripture has been twisted and omitted throughout history in children’s Bibles as a strategy for social control. For example, some missionary Bibles left out the crucifixion, because, as Bottigheimer asks rhetorically, “Why should anybody join a religion where the leader gets crucified?” The Tower of Babel story goes missing from 19th-century Victorian editions, because building and public works were in full swing in London and beyond, and God evidently didn’t like buildings. Eighteenth-century European children’s Bibles written for the poor emphasize obedience to parents and even implied a justification for infanticide, she discovered. And so on.

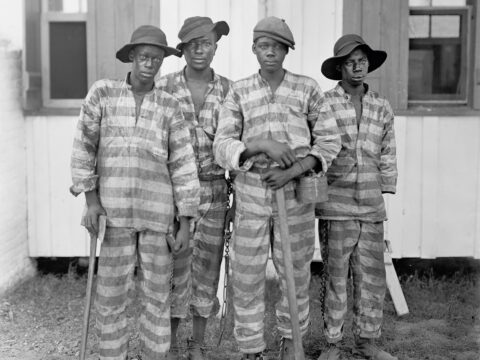

The Bibles that many of today’s adults were raised with are just as biased in their interpretations of scripture. Russell W. Dalton, professor of religious education at Brite Divinity School in Texas, blames American children’s Bibles from the early 1800s to the middle of the 20th century for diminishing the Christian invitation to act for change. In his 2014 article “Meek and Mild: American Children’s Bibles’ Stories of Jesus as a Boy,” Dalton argues that they overwhelmingly promote “virtues such as meekness, obedience to those in authority, hard work and contentment with one’s station in life. In addition, these materials often ignore or downplay potential meanings in Bible stories that might inspire more prophetic virtues such as speaking truth to power, standing up for justice, and promoting radical inclusion.”

In a research paper for a master of arts in theological studies at Vancouver’s Regent College, Rachel Wilkowski calls on the entire church to take more responsibility for the future of children’s Bibles. Many of them, she found, reduce each story to a simple moral lesson. That’s not how the Bible was written, she argues, is not appealing to children and is a weak foundation for adult faith. “Naomi and Ruth become a story about friendship, like, ‘You should be a good friend, too,’” Wilkowski explains. “It really limits the ambiguities of a text….I wonder if children’s Bibles do too much of telling children what to think instead of drawing them in.”

As much as children’s Bibles are selling well globally, in Canada, sales figures are lethargic. In fact, the vast majority of Christian books sold for children here are not children’s Bibles at all. BookNet Canada tracks sales in most English-language bookstores and websites. In 2019, 20.2 million children’s books were sold. Of those, 435,800 were Christian titles (2.2 percent). And just 5,100 were Bibles (0.03 percent) — though it should be noted these figures don’t account for Bibles sold through Christian independent bookstores or international websites.

Instead of Bibles, Canadians seem to gravitate toward middle-ground books, says Tony Federici, HarperCollins Canada’s director of religious sales. Over the past decade, Canadians have generally sought resources that are not overtly religious, such as Girl, Wash Your Face, a 2018 self-help guide and memoir by blogger Rachel Hollis. “People want books and resources to help them be better people and to feel better,” Federici says from his office in Coquitlam, B.C.

As an example of a middle-ground book for children, Federici points to Joanna Gaines’ and Julianna Swaney’s We Are the Gardeners, which “reminds kids to be gentle and understanding, without being preachy or talking about Moses,” says Federici. “We’re putting a lot of stock in the idea that this trend is going to happen. That these books will cross over.”

This middle ground is, of course, a place secular superhero comics have occupied since their inception. Over the past few decades, Christian themes have emerged from mainstream publishers. To any skeptics, Tomlin recommends two series. First, Kingdom Come (DC, 1996) is an apocalyptic dystopia featuring Wonder Woman, Batman and others. “It’s a riff on the Book of Revelation in a superhero context,” says Tomlin. “The main character, a priest, is being led through a future where superheroes have gone wrong.”

Second, he suggests reading Watchmen (DC, 1987). “This is not for the overly pious,” he says. “It’s about human sin and what human sin can do, the lengths people will go to try to be their own God and control the world we live in.”

For a theological and spiritual foundation, comics may not be enough, of course. Tomlin reads his own elementary-aged daughter The Jesus Storybook Bible, and she has taken on The Big Picture Interactive Bible, a Christian Standard translation. They complement her secular comics reading, which includes Archie and DC Super Hero Girls.

Given their vast publishing numbers in the United States, children’s Bibles clearly sit alongside comics, dystopian fiction and classic children’s literature on the bedroom bookshelves of millions of young people, as they do in Tomlin’s home. As long as children’s Bibles get cracked occasionally, they’ll continue to augment Marvel and Disney in young people’s search for truth, the call to righteousness and their relationship to forces greater than themselves. Miraculously, after 850 years in print, children’s Bibles might just outlast the church itself. That’s a big, comic-style “Bang!” if you’re counting. Not a whimper.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s September 2020 issue with the title “The wonderful world of children’s Bibles.”

Pieta Woolley is a journalist in Powell River, B.C.

I hope you found this article from Broadview engaging. The magazine and its forerunners have been publishing continuously since 1829. We face a crisis today like no other in our 191-year history and we need your help. Would you consider a one-time gift to see us through this emergency?

We’re working hard to keep producing the print and digital versions of Broadview. We’ve adjusted our editorial plans to focus on coverage of the social, ethical and spiritual elements of the pandemic. But we can only deliver Broadview’s award-winning journalism if we can pay our bills. A single tax-receiptable gift right now is literally a lifeline.

Things will get better — we’ve overcome adversity before. But until then, we really need your help. No matter how large or small, I’m extremely grateful for your support.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher

I recall receiving David Cook’s PIX each week at Sunday school. Thinking back, I likely obtained more theology and Bible knowledge from it. It certainly made the church service move a lot quicker. (We didn’t have junior church).