“Climate change scares the s**t out of me,” blurts out 10-year-old climate activist Brynn Kilpatrick, before stealing a glance at her mom. Brynn grins, knowing she’s broken a rule. Kendra, her mother, lifts her eyes from her papers and gives a reprimanding glare but says nothing.

“Girl Boss” is embossed across the front of Brynn’s T-shirt. Piled at the end of the dining room table are Greta Thunberg’s No One is Too Small to Make a Difference, and We Are All Greta, by Valentina Giannella.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

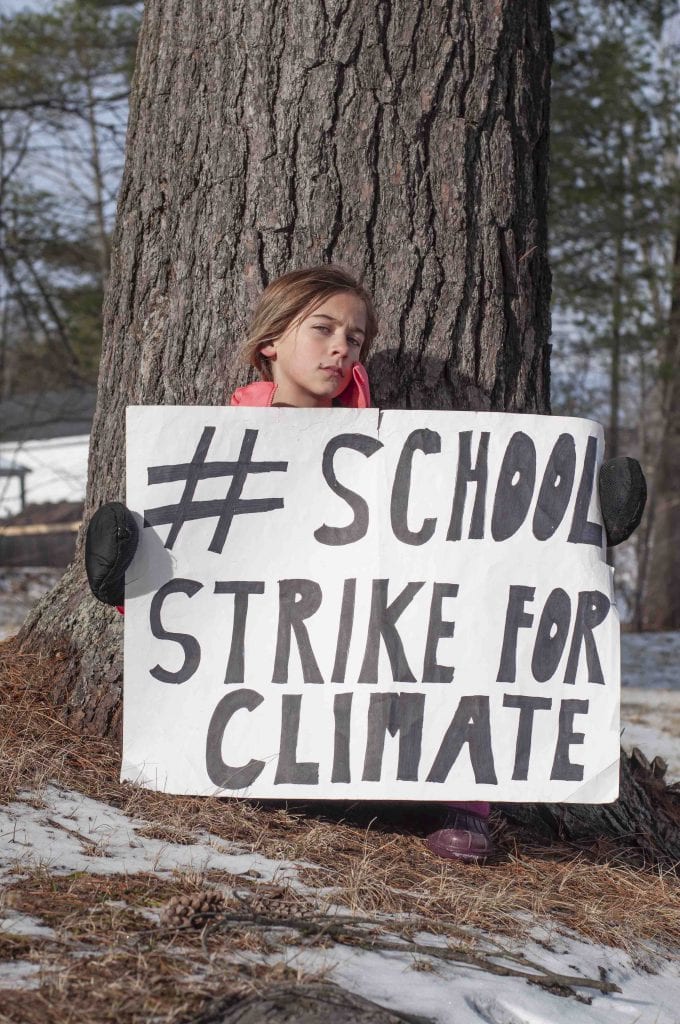

Inspired by Thunberg’s climate school strikes, Brynn began protesting on her Friday lunch break. But in her hometown of Bancroft, Ont., a place struggling to adapt to changing economics, she has received far less support than her role model.

“I was really depressed thinking about the climate,” she says. But watching Greta and doing this helps me feel better. I started protesting the Friday after last spring break [in 2019]. My parents were talking about Greta Thunberg. I asked who she was.”

“That weekend, we were making posters,” her dad, Bill, interjects. “She’s been out on main street almost every Friday since.”

“A man gave me the middle finger,” Brynn says, cutting off her dad and grinning again.

“How old where you when that happened?” I ask.

“I was nine.”

“Have other men given you the finger?”

“Yeah,” she answers, picking up her “Scruff a Luv” toy cat and combing its hair.

Like Brynn, Thunberg, 17, has also encountered rude behaviour from men while defending the environment. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro called Thunberg a brat, while U.S. President Donald Trump tweeted that the Swedish teen needed anger management.

“What do you think about men giving you the finger?” I follow up with Brynn later.

“I feel like they are going to be the ones that are killing the earth the fastest because they obviously don’t care,” she says. “They are going to continue going around by plane, taking their truck two minutes to a friend’s house, instead of walking. They are the ones who will be killing the earth and themselves the fastest.”

Climate historian Martin Hultman argues men are challenging climate science because it is a direct attack on traditional views about nature and the economy. In his study of climate change denial in Sweden, Hultman found that most of the opposition was coming from men. For centuries, the narrative has been that nature should be colonized, subordinated, and manipulated in the name of progress.

“It’s not just about money,” Hettie O’Brien writes in New Statesman. “It is a denial based on a long history of men thinking natural resources are there for the taking.”

Bancroft is a conservative town of 3,800 tucked in the woods of east-central Ontario. Traditionally, the region was known for its hinterland economy: male-dominated fields such as forestry, mining, hunting and fishing. Now, the mines are gone, and the forest industry represents less than three percent of county income.

According to Statistics Canada data from the 2016 census, 12 of the 16 municipalities that comprise Hastings County have poverty rates above the provincial average of 14.4 percent. In Bancroft, a quarter of residents live in poverty.

The town’s economy is now primarily based on cottagers, Toronto retirees, 150,000 annual tourists and the service jobs they produce.

The area is straight out of a cottager’s dream. There are 100 lakes within a 30-minute drive from town. A million-dollar home sold in Toronto can get you a beautiful lakeside house, and you would still have $600,000 in your pocket. While locals struggle to pay bills with seasonal minimum-wage jobs, the newly arriving rich are opening main-street art galleries and espresso bars.

Rev. Lynn Watson oversaw the “out of the cold” program at St. Paul’s United (it closed in January, unable to meet demand and provide training to staff). Born and raised in Bancroft, she understands the new economy in stark terms. “Tourism is a slave economy,” she says. “People work like dogs all summer, and starve all winter.”

Poverty complicates any discussion of environmental issues. Developers build mansion-sized cottages; people whiz around the lakes on power boats, or rip up forest trails on ATVs and snowmobiles. These all come with an environmental cost, but they add needed dollars to the local economy.

Watson supports Brynn’s strike. “But Brynn’s protest is just the tip of an iceberg of problems here,” she says. “The poverty is crushing. Drug addiction is a major problem. There’s almost no mental health services. It’s a constant fight with the province for money. Plus, I’ve had evangelicals tell me that climate change is God’s way of bringing on the second coming.

“When people say ‘I don’t care [about the environment],’ this is a real crisis of faith,” Watson says. “This is the challenge. This has to change.”

Brynn, on the other hand, cares deeply about climate issues.

“The environment is something that we all need to stay alive,” she says. “And it is also something we need for oxygen, air, food; it’s a big thing.”

When asked what she wants her protest to achieve, her wishlist is peppered with the word ‘hope.’

“My hope is that plastic will be banned,” Brynn says. “I hope people will use their vehicles less. My main hope is that people focus on their kids and think about what they are doing to the Earth and how it will impact the future.”

Paul Jenkins, Bancroft’s mayor, says he sees a push to deal with climate issues in the region. “I believe a vast majority of residents — new and old — are concerned about environmental issues,” he wrote in an email, adding that the creation of a “community green plan” is a priority for 2020.

The town released a four-year strategic plan in December 2019, which laid out its economic goals. The blueprint made no mention of climate change.

More on Broadview: Seniors group empowers peers to help fight climate crisis

“The Strategic Plan we just developed,” Jenkins says, “was an economic development plan, not an all-encompassing strategic plan.”

This separation of economics from the environment came to the fore last year when Faraday Township, adjacent to Bancroft, approved a new 70-acre drill and blast quarry. Its proposed location is less than a five-minute drive from Bancroft’s downtown.

Opposition to the quarry has divided residents. More than 800 people signed a petition against it. On the community Facebook page ‘No Place for a Quarry,’ people have raised concerns about increased dump truck traffic pollution, the few jobs the quarry will create, and how it will disrupt cottagers living on Bay Lake, which is immediately adjacent to the proposed site.

Others, however, argue online that economic self-sustainability is paramount. Some have conflated Brynn’s protest with the quarry protest, and say that Brynn would do better to stay in school.

Brynn, for her part, isn’t a fan of the project.

“The quarry is a big part of climate change,” she says, “because they are blowing stuff up just to make money. They are blowing up our earth and that’s not right.”

In a letter to the Bancroft Times, Madeleine Marentette, owner of The Grail Springs, an internationally recognized luxury spa which will be less than 900 metres from the blast site, asked how she is to maintain her business with a quarry located so close by. The spa is one of the town’s largest private employers, and epitomizes the change in Bancroft’s economy. “How do we mitigate blasting, drilling and crushing [stone] when tourists are hiking trails, participating in classes in meditation and yoga on the lawn, outdoor massage, canoeing, or enjoying one of our many outdoor events?” Her letter points out that the jobs created by the spa are mainly held by women – meaningful careers with benefits.

Marentette has appealed the quarry’s approval to the province. But few locals can access the spa’s $300-a-night price tag (winter rates). What the supporters of the quarry understand is resource extraction and trucks hauling gravel – traditionally male-dominated work.

I talked with my uncle, Murray Bowers, a Faraday Township councillor who voted for the quarry. “The proposal went through extensive environmental assessments,” he says. “The Ministry of Natural Resources, Oceans and Fisheries, Mines and Energy, and other government agencies signed off on this project. A blasting survey was done. We were told it will have minimal effects. I want to protect the environment too. But we have to be realistic. Gravel is needed every day. Would it be better to truck it in from far away, or to make our own, right here?”

“I feel like they are going to be the ones that are killing the earth the fastest because they obviously don’t care.”

Brynn Kilpatrick, on men giving her the finger

When I ask Brynn if other students are supporting her, I get a resounding “No!”

“It’s mostly been adults,” she says. “My school doesn’t support it and I don’t think many parents do.” When Brynn’s father tried to take a photograph of Brynn with her protest sign outside of her school, the principal informed Bill that they had to leave the property. An argument ensued and Bill received a restraining order from the school. Inquiries to the principal and superintendent went unanswered.

Dianne Eastman, a 68-year-old retiree from Toronto, has been attending Brynn’s Friday climate strikes since the beginning. “I have always thought of myself as a pro-environment sort of person. I took one of the first ecology courses offered at university in 1969. I make compost. But I have been in a fog,” she says.

Thunberg’s activism, Eastman says, got her out of that fog. “Greta’s strike is the most amazing thing that I have seen. I saw the first photo of Brynn with her sign that first Friday. I was filled with joy. The next Friday I was with her.”

The proposed quarry highlights a hot issue, Eastman says. “The environment tends to be overshadowed by the ‘whose-side-are-you-on’ question. There have been honks of support for Brynn, but there is also a lot of anger.”

Even older students have avoided Brynn’s cause. “People are so blinded,” says recent high school graduate Esther Mayer. “Someone else will do the changes, or they have ‘the world’s gonna end anyway’ mentality.”

“Boys don’t want to be called ‘p*****s’ for supporting Brynn,” says a male high school student who wished not to be named.

Still, Brynn has been recognized for her activism. Algonquin Chief Stephen Hunter gave her an eagle feather last April in recognition of her protests. The Bancroft Stewardship Council donated 100 saplings, to be planted around Bancroft in Brynn’s name. And she has also inspired other locals. Her protest now draws about a dozen regulars, and a community member started an initiative called “Bags for Brynn,” hoping to raise $2,500 for environmental causes by selling designer produce bags.

Brynn sees the pros and cons to having her activism in the spotlight in her small town.

“I feel like the positives outweigh the negatives,” Brynn says. “Most of the attention I get makes me feel happy, like I’m doing something, but some of it makes me feel like we need to step up our game a bit because people still aren’t caring.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Well done Sherwood. Us adults are not doing enough.

Proud of our young lady!

On the Freymond Quarry…three jobs, we where told by the company who will be blasting our homes will shake…this will ruin our town.

The author didn’t care to mention how many people signed the petition in support of the quarry I guess. It had over 1500 signatures in less than a week, when the opposing one was active for weeks, for anyone wondering.

With all the love for cottagers and tourism in this article, does anyone else see an issue with their excessive use of fossil fuels every single weekend?

That “male dominated” quarry is proposed by a family business with women in leadership too. I’m proud to know them so well.