A handful of initiatives are helping to prevent those with mental illness from being incarcerated in the first place and get them the support they need instead. In Ontario, for example, the Hamilton Police Service is known as one of the more progressive police forces when it comes to mental health awareness.

Hamilton police officers and communications workers take a 40-hour mental health crisis training course, which includes people with mental illnesses and their families sharing their experiences and how they’d like to see things improve. The service also has a Mobile Crisis Rapid Response Team (MCRRT), which is the first of its kind in North America. Partnering with St. Joseph’s Healthcare, a local hospital, a mental health professional joins an officer to respond to calls involving people in crisis.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“Some people respond better to the mental health worker,” one of the MCRRT workers, Sarah Burtenshaw, told the CBC. “And sometimes to the officer. We’ll do what works for that person.”

More on Broadview: After Soleiman Faqiri’s death in jail, advocates call for change

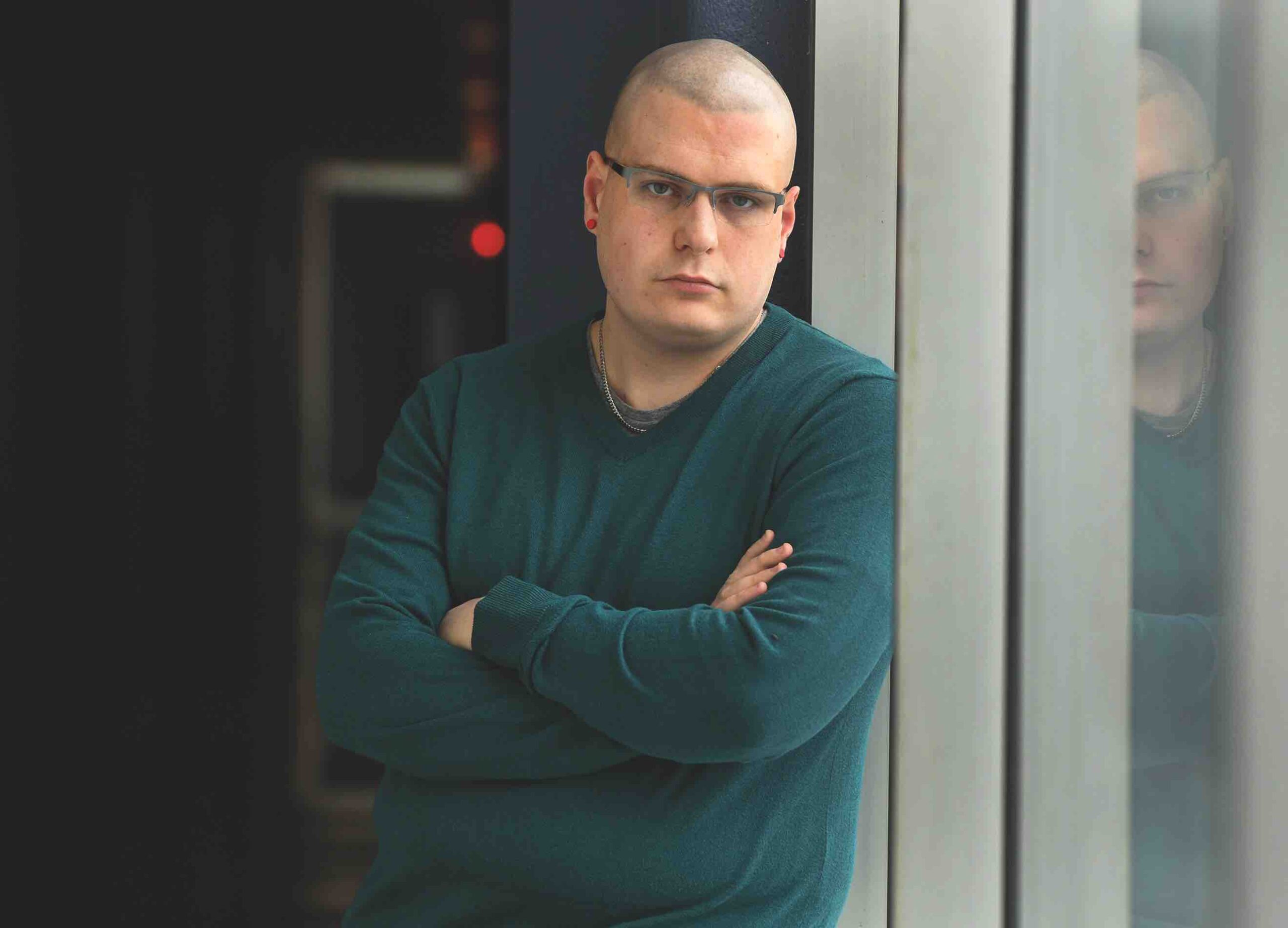

Arthur Gallant is a Hamilton-based mental health advocate and is diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia and borderline personality disorder. He has been apprehended by police under the Mental Health Act almost three dozen times. He notices that when police respond to a crisis alone, they spend less time talking to him and are quicker to send him to a hospital, which can be traumatic.

But when a police officer is accompanied by a mental health professional, says Gallant, they take more time to ask questions and de-escalate the situation. When this is the case, Gallant has never been sent to the hospital.

The statistics back up Gallant’s experience. With this program, the police lowered their average apprehension rate while responding to people in mental distress from 75 to 12 percent. “What that means is we’re getting the appropriate services to the appropriate people at the right time,” says Sgt. Steve Holmes of the Hamilton Police Service’s crisis response branch.

This story first appeared in the January/February 2020 issue of Broadview with the title “A new way forward.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.