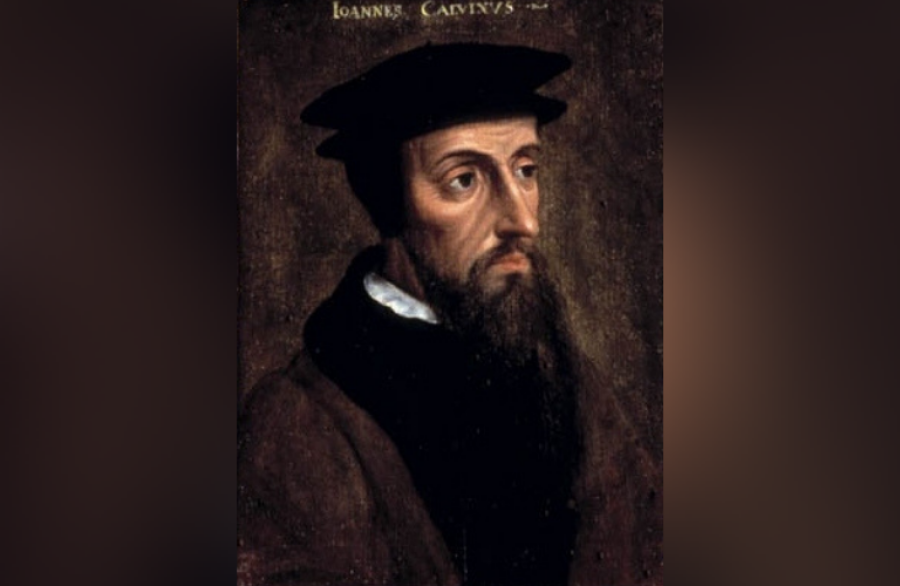

This year in Geneva they are making special chocolates, brewing a new beer and venting a fresh wine. The reason: the 500th anniversary of the birth of their most famous adopted citizen, John Calvin. John Calvin is important to us in the United Church, too. He is one of our great spiritual forebears, a theologian who spawned an international movement in 16th-century Europe that laid the foundation for two of the churches — Presbyterian and Congregationalist — that evolved into The United Church of Canada in the 20th century.

But wait — wasn’t Calvin also the founder of a repressive form of Christianity?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

True, with the bit in his teeth, Calvin was capable of intransigence and vindictiveness. But this is nowhere near the whole story. Beyond the distorting stereotypes, half-truths and just plain ignorance that fuel the image of a theocratic despot, Calvin waits to be discovered anew. This anniversary year is an apt occasion to do it.

Let’s examine some myths about the great reformer.

Myth: Calvin ruled Geneva as a theocracy.

In 1536, Calvin arrived in Geneva as a refugee from France after breaking with the Roman Catholic Church. Like other French refugees, he was always viewed as an outsider by establishment Genevans. Though Calvin possessed great influence through daily lecturing and weekly preaching, the only public office he ever held in Geneva was that of chief pastor. After serving for only two years in that role, he was dismissed by the state council, returning at its invitation in 1541. They could neither live with him nor without him.

The longer Calvin stayed in Geneva, the more his influence grew. He was a celebrity preacher whom travellers went out of their way to hear. His direct denunciations of the unethical behaviour of the good burghers and magistrates of Geneva sometimes resulted in fights breaking out on the church steps. His published writings, including the multi-edition Institutes of the Christian Religion and commentaries on most of the Bible’s books, earned him an international reputation. Young church leaders fleeing Catholic persecution came from all over Europe to study with him, and when they returned home, took his teachings with them.

Yet throughout most of his time in Geneva, political control of the city was in the hands of those opposed and even hostile to their chief minister. At his own request, Calvin was buried in an unmarked grave after he died in 1564.

Myth: Calvin believed goodness was alien to human nature.

Calvin certainly believed that sin profoundly affects all humans. “Total depravity” is the phrase that comes to mind. However, what he meant is that there is no aspect of human nature unaffected by sin. Medieval theologians usually taught that the tinder of sin is in our bodies and that the mind can rise above our carnal appetites. Calvin rejected this body-mind dualism, insisting that the human mental and imaginative faculties are as susceptible to sin as the body. The mind, he said, is a “factory of idols.”

Calvin interpreted Genesis 3 to mean that sin enters the world through human unfaithfulness to God. This unfaithfulness and falling away from God is first evident in human ingratitude for God’s gift of creation. As the eminent American theologian Brian Gerrish has observed, “Calvin’s disgust at human ingratitude, not disgust with humanity, lies behind his rhetoric of sin and depravity.”

Myth: Calvin was an unforgiving disciplinarian.

Calvin and his ministerial colleagues met weekly with selected magistrates in the consistory, a forerunner of the church Session, to deal with problems and offences related to moral life. The consistory minutes record interviews and actions dealing with matters ranging from domestic quarrels to continuing Catholic devotional practices to public drunkenness. What may come as a surprise is that they reveal consistory members to be more concerned with achieving understanding and healing than simply imposing punishments.

Myth: Calvin was obsessed with personal morality.

Calvin’s insistence on living the Christian life was directed at more than individual spiritual regeneration. He believed that the reign of God proclaimed by Jesus includes social well-being — Christ came as the transformer of both individuals and cultures. Calvin was an untiring advocate for the refugees and poor in Geneva throughout his ministry, teaching that social solidarity is an imperative of the image of God in humanity. We are bound together by a “sacred cord” and are responsible to one another for mutual aid and assistance.

Calvin saw not only the social implications of God’s redemptive work in Christ, but also the cosmic. He understood that the whole of creation was “bound for glory” and that even inanimate creatures would be perfected in God’s culminating work. Indeed, Calvin viewed the creation as a “dazzling theatre of God’s glory” and as “the garment in which God clothes himself.” While it is in Christ’s passion that we see God’s heart, it is in the works of creation that we see “God’s hands and feet.” We could use more of his ecstatic reverence for creation today.

Myth: Calvin was a champion of self-denial.

Calvin did have a great deal to say about self-denial, cross-bearing and “mortification of the flesh.” Yet this reputedly negative and narrow viewpoint had as its goal more than straitening discipline for the believer. It actually was aimed at generating support for the disadvantaged. In promoting an ethic of self-denial, Calvin was calling the relatively affluent to give up some of their substance for the benefit of others. Disturbed by the enduring co-existence of wealth and poverty, Calvin believed that the unequal distribution of goods in the world should provoke believers, especially well-off ones, to generosity toward the poor. The poor, he believed, are “God’s proxies,” sent “as agents to gather in what is God’s.”

Myth: Calvin was the spiritual father of capitalism.

Calvin was the first European theologian to defend the lending of money at interest and so incurred the Catholic criticism that “usury is the brat of heresy.” However, money was already being lent throughout Europe at rates of 12 and 14 percent by the Christian kings of England and France. (In Geneva, the rate was capped at five percent.) Living in the time of transition between the middle and modern ages, Calvin understood that a principled realism needed to replace an unsustainable idealism about “filthy lucre.” In the turbulent economy of 16th-century Europe, he discerned that businesses need credit to get started and thus provide employment for workers — among them Geneva’s many refugees. Calvin defended only those interest-bearing loans that would benefit lender and borrower alike.

Myth: Calvin was the source of a debilitating work ethic.

It is actually the market that defines the “work ethic,” by setting a value on one’s worth and achievements. Calvin did teach that prosperity achieved through honest effort can be a secondary sign of “election” — of being chosen by God for salvation. However, he never viewed human achievement and prosperity as the source of meaning in one’s life or as the cause of one’s salvation. Rather, we are saved by the gift of God’s mercy. The only work that “earns” salvation is work accomplished on our behalf by the ministry and self-offering of Jesus Christ. Christ is “the bright mirror of election,” and those in right relationship with him can be confident about their worth and destiny. If Christians do work hard and enjoy some achievement, especially in service of God’s reign, they do so in joyful freedom and in grateful response to God’s unfailing grace.

One of the more profound articles appearing “here” in decades. But sadly, too little and too late.

Even as we are surprised at learning about Calvin (and important things too, relevant and good – although in addressing negative myths Calvin’s influence on education and intellectualism is missing) we realize this article is a sad cork bobbing on an ocean of loss.

The chain of discourse was broken long ago. We visit the museum and discover a glorious history. And then walk out the door. Because the faith matrix which nurtured engagement is missing. Foolish myths about Calvin?? Who dat?