The Grapes of Wrath was released nearly 80 years ago, and it remains the standard by which all movies about poverty in America are measured. Director John Ford’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel about the westward migration of destitute tenant farmers during the Great Depression was a triumph of empathetic realism. At the time, critics hailed it as a sign of an emerging social conscience in Hollywood.

They were overly optimistic. Poverty in America remains one of Hollywood’s least-popular subjects. A University of New Hampshire researcher calculated that in the entire history of American commercial moviemaking, only about 300 films deal significantly with poverty. Of those, just a handful can be considered even remotely in the same league as The Grapes of Wrath. Mostly Hollywood treats poverty as something to gawk at, deride, fear or idealize.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

A hint of a shift came two years ago with Moonlight, an intensely personal, Oscar-winning coming-of-age story set in poor black neighbourhoods in Miami and Atlanta. Last year, three new releases spotlighting the white American underclass — The Glass Castle, I, Tonya and The Florida Project — seemed to confirm a trend.

Why now? Is Hollywood buying in to the idea that America isn’t great anymore? Is it playing to the anxieties of mainstream audiences who fear they’re next if things don’t improve? Perhaps the burgeoning underclass has simply become too glaring an issue for moviemakers to ignore.

Both I, Tonya and The Glass Castle are based on real-life stories — the rise and fall of 1990s figure skating star Tonya Harding, and the transient childhood of New York celebrity journalist Jeannette Walls — and both suggest that Hollywood still hasn’t got poverty quite right. I, Tonya is as cold-hearted as a movie can be. The attack on rival Nancy Kerrigan that led to Harding’s banishment from figure skating comes across as the kind of tabloid stunt you’d expect from people who come from her side of the tracks — people like her abusive husband and her pushy, chain-smoking, potty-mouthed mother, played by Oscar winner Allison Janney. Any sympathy we’re asked to muster for Harding as the plucky underdog who succeeds in a sport for the affluent is tempered by the scorn the film heaps on her background.

The Glass Castle, based on Jeannette Walls’ 2005 memoir, shares a similar view of the underclass as a breeding ground for self-destruction, although the approach is less spiteful. The film alternates between Walls’ chic life in New York and her hardscrabble, nomadic upbringing in a family dominated by her father (Woody Harrelson), a nonconformist haunted by his backwoods past. For a time, they live pennilessly but carefree, until her father’s demons propel the family downward.

A sense of inevitability runs throughout the film. Walls’ father, the story suggests, suffers from a failure of self-awareness endemic to his class: he’s stubborn because of his deprived background, and because of his stubbornness he’s condemned to return there. Rather than empathize with him, we’re left shaking our heads.

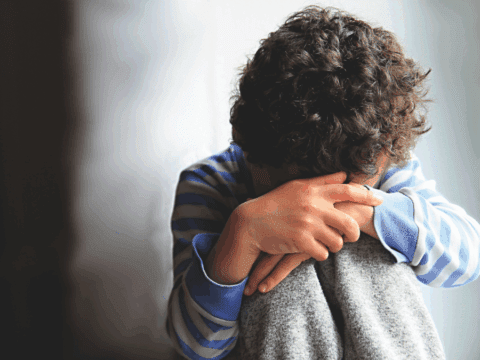

The Florida Project, on the other hand, grabs our hearts. Moonee (Brooklynn Prince), a precocious six-year-old, lives with her rebellious young mother, Halley (Bria Vinaite), in a welfare motel in the shadow of Disney World. The film doesn’t recoil from their poverty; it asks audiences to judge them on the strength of their character, not their circumstances. It’s closer to the spirit of The Grapes of Wrath than any film in recent memory.

The Magic Castle motel on Orlando’s woebegone outskirts is like the California relief camp where the Joad family winds up in Ford’s movie. More than a gathering place for the luckless, it’s a community where people accept one another and have each other’s back. The motel manager (Willem Dafoe) sets the moral bar. The residents aren’t angels, but they’re his people, and heaven help anyone who tries to do them harm.

For Moonee and her friends, the strip-mall neighbourhood around the Magic Castle is an enchanted kingdom. They run wild and know things kids their age probably shouldn’t. But at the end of the day, after they’ve monkeyed with the motel’s power supply or conned free ice cream for their “asthma,” they go back to motel rooms that are, for better or worse, home, and to parents who love them as much as the tourists who are dropping a fortune a few blocks away love their kids.

Moonee’s mom, Halley, is an out-of-work exotic dancer and server who tries to make ends meet by selling knock-off perfume to gullible tourists. We feel a growing admiration for her, even as she resorts to desperate measures to provide for her daughter. Halley defies conventions of what makes a “good” mother, but there is no denying that she is one, in her own way. Toward the end of the movie, when the rules of good parenting confront her head-on, her pain is ours, too.

The Grapes of Wrath ended ambiguously, with farmer-turned-union organizer Tom Joad vanishing with a vague promise to “be there” wherever the downtrodden are fighting for justice. It was the movie’s way of telling audiences — mistakenly, as it turned out — they haven’t seen the last of the underclass in film. The Florida Project ends inconclusively, too. Viewers are left to imagine what will become of Halley and her rebel-in-training daughter; perhaps our projections will reveal something about our personal perceptions of poverty. The film’s open-endedness also implicitly challenges Hollywood to keep telling the story of poverty in America, with empathy and goodwill. Is Hollywood ready to “be there” this time?

This story first appeared in The Observer’s May 2018 edition with the title “Rise of the underclass.”