In 1996, Ralph Milton, then president of the B.C. Conference of the United Church, turned to the theme of death for his final speech at the annual meeting. He quoted from a poem by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas whose refrain runs, “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” But Milton didn’t rage against it. Nope. He advised us to just “go gentle” into that good night. In other words, die, church, die.

I was 21 at the time, attending the meeting as a youth delegate. The church was my life. Ever since my mom had married a United Church minister 10 years earlier, I’d been swirled up into a vortex of youth groups, inner-city service, congregational potlucks, camp leadership and regional retreats. I found social acceptance. I found ways to make a difference and the direction to do so. Most importantly, I was introduced to confession and divine grace — the cure for the worst parts of being human. And forgiveness — the oil in the gears of living with other humans.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

So I wasn’t hip to the church going anywhere, gently or not. “How rude of Ralph,” I thought.

So did Allison Rennie, B.C. Conference’s youth and young adult minister at the time, who (in my memory) pushed back against Milton’s “go gently” message in a pointed and rousing speech from the stage. It made for some riveting back and forth.

In his president’s report, Milton asked why the church is in sharp decline. “If we embrace the question,” he wrote, “knowing we cannot understand or answer it, we will find joy and meaning and hope in our last and perhaps greatest commission. To die well.”

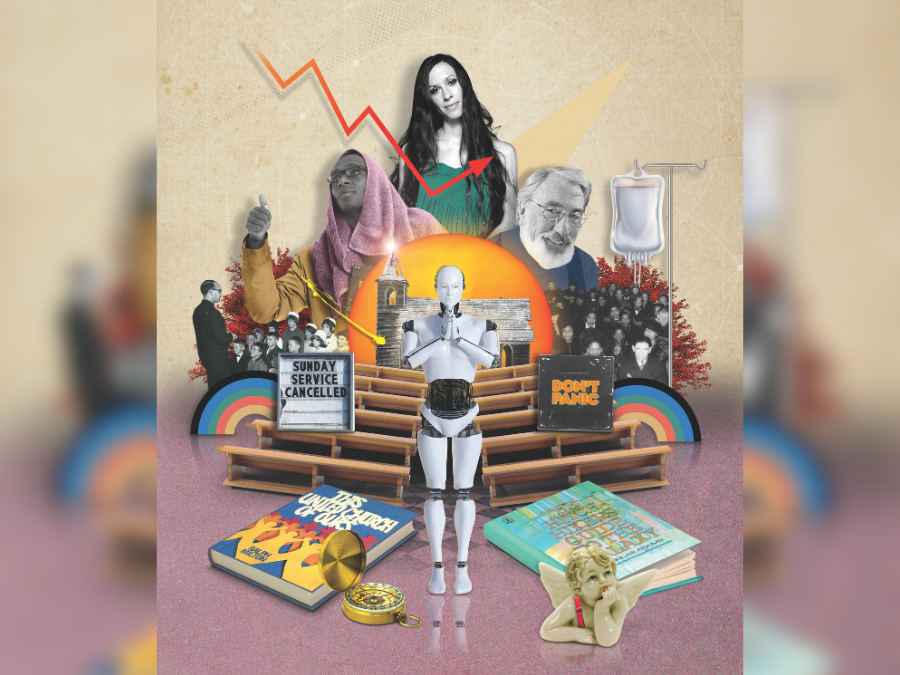

I should have paid more attention to Milton because he, like me, loves the church. He is also this church’s storytelling luminary, something I didn’t fully understand in 1996. But I do now, and maybe so do you. He’s the author of This United Church of Ours (1981), the most-bought book in United Church bookstores after the Bible and hymnals. Now in four editions (the latest is 2017), the book is a cozy Hitchhiker’s-Guide-to-the-Galaxy-style introduction to the culture and theology of Canada’s largest Protestant denomination.

Milton also wrote the bestselling The Family Story Bible (1996), Angels in Red Suspenders (1997) and Well Aged: Making the Most of Your Platinum Years (2021). The company he co-founded, Wood Lake Books, published the Sunday school curricula Whole People of God and Seasons of the Spirit, and much more. As Stuart McLean was to CBC, so Ralph Milton is to the United Church. That means when Milton looks out onto 500-plus delegates at a 1996 meeting and tells us it’s time to go gently, it’s a shock worth our attention.

The United Church was 10 when Milton was born; he is 90 now. He lives in a retirement community in Kelowna, B.C., with his wife, “Rev. Bev.” When they’re up for it, they attend Central Okanagan United, a thriving congregation and community ministry of 400 families. While he’s truly inspired by the energy and creativity there, he’s also seen the United Church in this region collapse from four congregations into one between 2021 and 2023. That sole congregation now serves a community of about 153,000.

No one I know loves the United Church more than Milton; no one, perhaps, is as clear that it’s on life support.

“I feel that I am living in the last era of the church,” Milton said in a phone conversation from his home. “I can’t imagine it lasting more than another generation, for various reasons. But the main one is people are bored with the story the church has to tell….It makes me feel quite sad, but that’s the reality of it.”

Indeed, the future of the church, in Sunday morning numbers, looks very much like no church at all.

For more than a decade now, the phrase “one United Church congregation closes every week” has rumbled through conversations about the church’s future. Numbers vary from year to year, of course. In 2022, 64 congregations closed or amalgamated; in 2023, 66, and in 2024, just 31. That’s an average of about 54 congregations a year. If that many continue to close each year, the end of The United Church of Canada as a congregational church will be in about 2070.

More on Broadview:

-

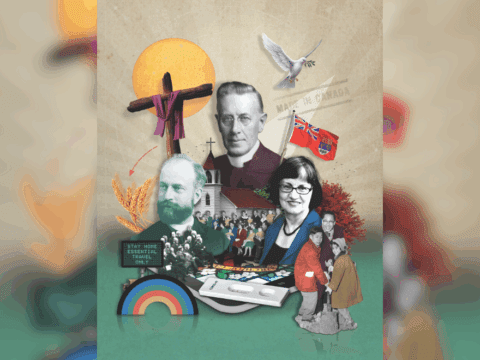

The United Church was forged in the fires of the social gospel

-

United Church moderators reflect on the past, present and future

Looking at the shrinking of congregations through a wider lens, there were 7,633 United Church congregations in its biggest year, 1930, just five years after union. (The church didn’t start collating attendance until the late 1970s.) If the number of United Church congregations had grown at the rate of Canada’s population since then, there would be about 30,000 today. Instead, by the end of 2024, there were just 2,442.

Since General Council began keeping statistics on weekly attendance in 1977, the greatest average number of Sunday worship attendees was in 1984, at 403,707. Average attendance in 2023 was about a quarter of that, at 110,878. If you do the math, that works out to an average of about 45 worshippers per church on a given Sunday today. In other words, if you think there might not be a future for the United Church, you’re on the pulse, centenary celebrations or not.

What do we do when someone we love is dying? Normally, we rage, rage against the dying of the light.

***

Ruminating about the ultimate demise of the United Church has been an engrossing, if futile, pastime of this denomination for at least two-thirds of its century of history. Back in 1967, The Observer magazine published a page of predictions about the United Church of 2067, by editor Rev. A.C. Forrest. They include gems such as “over 90 percent of Canadians will tell the census-taker they are Christian,” and “The most influential [denomination] will be the Church of Christ in Canada formed by a union of United, Anglican, Presbyterian and some other denominations.”

Although the list blusters with confidence, that same year, The Observer ran this headline: “DISAPPOINTMENT: For the first time [since 1925] United Church membership did not grow last year.” Membership had dipped from 1,064,000 in 1965 to 1,062,000 in 1966, a drop of less than two-tenths of a percent. The article takes the decline very seriously and notes that “the revival is over, we may be in for a difficult time of retrenchment.” Baptisms, Sunday school attendance and candidates for ministry all declined in 1966.

The un-bylined article blames the new suburban affluence and states: “A great many people who once turned to the church for their social, cultural, and creative as well as spiritual life are spending more time at the curling rink, the golf club, the ski slopes, and the summer and winter home.” The article wraps up, rather unsatisfyingly, with this: “In many ways, The United Church of Canada has become a great servant church, ministering to vast numbers of decent people, and helping them to live more usefully. Lovingly. The levelling off of that statistical graph is disappointing. But to be discouraged by it would be unwise.”

Today’s church leaders also refuse to be discouraged. Even facing dismal numbers, General Council hasn’t succumbed to Milton’s prescription, to “find joy and meaning and hope” by dying well.

Instead, the goal is growth.

Starting in 2020, General Council Executive harnessed a vast swath of United Church people to contribute to a new strategic plan. The goal: “disrupting narratives of decline and despair in our church in the last years.” In other words, yes, the numbers look bad. Let’s do something about it.

In 2022, the Executive released The United Church of Canada Strategic Plan 2023-2025, with the hope that it will be used by congregations, camps, chaplaincies and others. It promises to develop 100 new communities of faith, with a focus on serving migrant communities, as well as changing “current ways of working towards new culture, systems and processes.” This is no cozy Hitchhiker’s Guide; it’s a business plan.

“Our overarching goal is to create the conditions for renewal, dedicating focus, energy and resources to slowing — if not interrupting — a decrease in participation, giving and impact,” it reads. In other words, we want more bums in pews, more chequebooks open, more clout. Or, perhaps more philosophically, more justice. Six strategic objectives lay out how to get there: embolden justice; invigorate leadership; nurture the common good; deepen integrity; strengthen invitation; forge right relations.

The plan’s first follow-up report, released in 2024, is a beacon of positivity. Each strategic objective is paired with an action. The 2025 release of Then Let Us Sing!, the new online music resource, is the example of invigorating leadership. A strategy to save congregations millions of dollars by containing insurance costs is a check mark next to nurturing the common good.

“I can’t imagine [the United Church] lasting more than another generation, for various reasons. But the main one is people are bored with the story the church has to tell.”

The strategic plan isn’t alone in its attempt to shape a confident vision for the future. Two books by Rev. Brian Arthur Brown, a prominent minister, academic and author from Niagara Falls, Ont., scoff at the narrative that the United Church is in decline.

First, Keys to the Kindom: Money and Property for Congregational Mission in the United Church of Canada (2022) is a financial history, illuminated by stories and on-the-ground profiles of the church’s financial heft. The denomination, Brown notes, holds one of the largest real estate portfolios in the nation. While congregations may fade away, the United Church has money in real estate, investments, foundations and cash. Congregations have raised half a billion dollars every year since 2018, he writes. As a group, they have cash on hand or investments of nearly $800 million apart from national funds and other sources of money. The replacement value of church buildings and their contents is nearly $5.3 billion, Brown asserts, and church land is estimated to be worth another $1.7 billion.

Second, The Untied Church of Canada: Unfettered for 2025 Celebrations (2023) tells a magnetic story about a denomination that, though smaller than it once was, is very much alive. “Despite media assessments that the United Church is a dying institution, there is inescapable evidence to the contrary,” Brown writes. Later, he argues, “I personally believe that all the churches that needed to close in this last so-called ‘decline’ have done so or will have done so by 2025…[and we should anticipate a] resurgence of strong, normal-but-lean church life in a new context.”

The United Church of Canada Foundation bought digital rights to Untied from Wood Lake Books, the original publisher, allowing for free distribution to members of congregations. Untied was originally supported by a grant from the foundation.

In a Broadview review of Untied, longtime minister Rev. Christopher White rebutted Brown’s “resurgence,” citing figures from Statistics Canada and the church itself: “Add to that the on-the-ground struggles many communities of faith and clergy are experiencing today, as well as the bigger picture — what is truly a collapse of the Christian church in the western world — and it feels like Brown et al. are shifting the blame to the messenger. Decline is everywhere, and Christians need to face it head-on.”

Probably, neither Brown nor White is wrong.

***

What is the future of the church? This isn’t something that can be answered by a central authority. It’s a personal question. As a journalist, I can string together some research and some context, but the deeper question lives inside each of us, and we all have our own conclusions.

To me, congregational life is essential to the survival of what’s most valuable about the United Church, and also, going to church is not something I want to do anymore.

It’s a problem.

I confess that, through my 20s, shortly after the 1996 B.C. Conference meeting, I stopped attending worship regularly. In my 30s, with young kids, we attended the United Church in Powell River, B.C. But as my kids aged out of Sunday school (which I was teaching), I found myself less willing to make the effort. COVID-19 killed it for me.

Why? Most churchgoers have their own stories about joining and leaving congregations. Congregations are hard at the best of times. As Milton said in our interview, “It’s always been rough for those of us who don’t want to colour inside the lines.” Congregations in existential crisis — as many are in 2025 — are particularly hard to attach to. So many tired committees.

For this story, I went to a Remembrance Day service at a downtown Vancouver church, just to jog my memory of the big urban worship experience. As always, I showed up full of feelings from the week’s events: guilt, shame, regret, sadness, worry and even some despair. It wasn’t a bad week, but 2024 was a terrible year for me with lots to ruminate about.

I’m a wife, a mom, a journalist and magazine owner. A first-world consumer and a small-town person. It’s a lot to carry, and I often screw it up. Not because I’m uniquely bad but because I am inescapably human, fallible to the full gamut of sin. Plus, the heaviness of living through this era lives inside me. Thanks to technology, I can see the graphic horrors of global news events in real time. Mostly, like everyone else, my insides are a mess.

As I entered the Vancouver church, no one greeted me in the narthex. Someone did ask me to join an environmental committee before I’d even found a seat. About 200 people were in church that day, and they greeted each other with hugs and handshakes. The service started with bagpipes. Confession was rushed. The minister was an excellent speaker and a clear thinker, but her sermon tried to pull together Remembrance Day, Trump’s election, a passage from Exodus and the idea that love is the one thing we can’t leave behind.

That so many showed up and sat so attentively showed that the congregation thrived on what she delivered. I just couldn’t connect to it. Being who I am, I don’t need help with news analysis or social justice action or connecting to people. I need to confess my sins so I remember what they are, accept God’s grace so I can get out of that dark hole, open myself up enough for holy music to wash my insides, humbly take communion and be sent out of the sanctuary “with a daring and tender love; the world has great need of it,” as my Rev. stepdad used to say. Instead, my insides were still a mess after the full worship experience.

I’m worried about the direction of the strategic plan. In the same way that joining a committee makes me feel tired, the strategic objectives make me feel like I’m at a corporate retreat. I wonder where my go-to, “greet new people in the narthex” is in the strategic plan. Or, “if people show up on a Sunday morning, you can assume they’re a mess; make sure you nail confession.” The basics, which Milton outlined so beautifully in This United Church of Ours, seem to be missing. Hospitality goes a long way, if you’re hoping for growth.

I could be wrong about all of this, of course. This is my version of “what’s wrong and how to fix it.” You have your own version. So does the General Council Executive. Ultimately, something most of us can agree on is that this United Church of ours is in trouble.

***

In the beginning of Douglas Adams’s 1979 bestseller, A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the hapless Englishman Arthur Dent faces the destruction of his two homes. First, his house is razed to make way for a bypass. Then, Earth is destroyed to make way for a hyperspatial express route. Dent, rescued from the exploding planet by his alien friend Ford Prefect, grieves both losses deeply and furiously. As they stow away aboard a passing spaceship, Prefect offers Dent a towel for comfort plus an electronic book with the words “Don’t Panic” on the cover.

The possible demise of our denomination is like the razing of Dent’s house: it feels personal, and while we should have the power to stop it, I wonder if we actually do. Worse, if we’re paying attention, our church is just one of the many institutions that have fostered social cohesion for centuries and are now on the chopping block. Churches, pubs, malls, libraries, service groups, social clubs, theatres. Adams’s Vogons — that alien race of ruthless civil servants — are here to make way for the hyperspatial bypass vaporizing these institutions before our eyes. Goodbye, human connection. Hello, iPhones on the couch.

The wonderful part of being 50 is that I’ve seen enough to glean some perspective. Pits of despair rarely last. Things change all the time, in unpredictable ways. A 17-year-old son who lives in his bedroom and speaks in grunts will become an 18-year-old world traveller, able to forge connections across language and culture. A friend, skeletal and bald from chemo, will reappear fully bearded and in a scuba suit. A garden one summer will grow only withered and blackened cabbage. The next, flowers bloom and tomatoes bulge. And then, sometimes, people who seem to be at the end of their lives actually die.

Being who I am, I don’t need help with news analysis or social justice action or connecting to people. I need to confess my sins so I remember what they are.

Then again, even Milton, in his 1996 president’s report, pulls back the throttle. That death of the church, he writes, is really about waiting for a new church to be born: “God give us the grace to wait and to pray and to love and nurture the embryo church within us — to see it to the moment of nativity. And then, in the sabbath time that’s left to our beloved [United Church], give that strange, confusing new infant church the greatest gift of all, our quiet, unassuming love, as we go gently, joyfully and hopefully into that good night.”

In the 1999 comedy film Dogma, protagonist Bethany Sloane humbly approaches God in the aftermath of an epic battle. God is played by Canadian alt-rock star Alanis Morissette. “Thank you for…I don’t know…everything,” says Bethany. “God, there’s a million things I wish I could ask you. Most of it questioning what I’m sure is your great plan and that would be really arrogant of me, I know.” God nods. “There’s one I need to ask, and I’m sure you get it all the time….Why are we here?”

God clicks her tongue, smiles, boops Bethany on the nose with her finger and squeaks, then walks away into a mist-filled cathedral.

That “boop” by Alanis-as-God is what ran through my mind as I read the strategic plan, Brian Arthur Brown’s works and my own first drafts of this article. That “boop” is also the towel in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, a soothing gesture that offers no real safety. Moreover, Alanis-as-God’s smile is the phrase on Dent’s electronic book, “Don’t Panic.” It’s not a promise that everything will be okay. It’s a reminder that resistance against God’s will is futile, but that we can face whatever comes at us with grace, humility and thanksgiving. It will be hard, but we can handle it.

God knows we can’t force people back into the pews. As the 1967 “DISAPPOINTMENT” editorial said: “There is something sociological here.” We have no real insight into God’s plan or what the future may hold. We do have the remains of what once was the magnificent, powerful, nation-shaping United Church of Canada and all the people — both in the pews and refusing to be in the pews — who earnestly, passionately love it.

Maybe God’s plan is the General Council’s strategic plan, and the United Church will grow again. Maybe cheery Brian Arthur Brown is right, and those looking denominational death in the eye are simply grouches who don’t understand trends. Maybe I’ll get over myself and join or create a congregation that does what I need it to do. Maybe not. Maybe none of these.

In any case, what can we do but keep on going out into the world with a daring and tender love? Because the world has great need of it.

***

Pieta Woolley owns qathet Living magazine in Powell River, B.C.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s June 2025 issue with the title “A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Future Church.”

I found Pieta Woolley’s article very well written & extremely thought provoking. It’s given me a lot to digest & wonder what does the future hold for us, the United Church of Canada? I found it depressing at the beginning thinking our church will disappear. What does the future hold for our children & grandchildren? What does the world hold for all of us. It looks pretty grim at times. What are we the people doing to the world? There is less empathy, caring for & looking out for one another. There’s more controlling & power struggle. How does God allow this to happen, or does he? Will we ever learn our lesson?

Then at end Pieta gives a more positive note. It is up to us to be more positive an spread more love & work for peace & growth, conscious & open to God’s guidance. May it be so!

Well the option of decline is ours. If we find a church in which there are no greeters and you noticed that shortcoming maybe that’s what you’re being called for. If we want the future of the church to be different we should invite those around us to join and experience it. The lack of confidence is what’s killing the church. We don’t invite people around us to join us. Most people probably won’t take that offer but someone will at some point and they can become an integral part of that community.

What a navel-gazing, incoherent screed. Milton and Douglas Adams. Really?