Americans do a great job of welcoming visitors. So it was no surprise to be warmly received at Pilgrim-St. Luke’s United Church of Christ last December.

With a stately, modernized building in downtown Buffalo, N.Y., the congregation has the city’s trendy Elmwood Village to the east and a Hispanic working-class community to the west. A three-year-old Spanish-speaking congregation, El Nuevo Camino, is also part of Pilgrim-St. Luke’s. The congregations post a rainbow-flag logo on their shared website and promise to welcome all, “No matter who you are or where you are on life’s journey.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

On a cold and rainy Sunday, friendly greeters in the church’s spacious lobby provide nametags, plus an invitation for cake and coffee after worship. Today, there’s a joint pageant in English and Spanish, led by co-pastors Rev. Bruce McKay and Rev. Justo González. Visitors also get a gift bag of candies, a fridge magnet and a pen bearing the church’s logo.

A six-member delegation from The United Church of Canada is sure to be greeted just as warmly when it begins talks with the United Church of Christ (USA) this month. Their aim: to reach a full communion agreement, a way for denominations to work more closely together without actually merging.

In addition to greater co-operation at a national church level, full communion could also mean local congregations on both sides of the border sharing their journeys as they seek to be the church in changing times.

The Canada-U.S. border is no great barrier to cross-border shoppers or popular culture. It’s also unlikely to prevent close relations between two United churches. The Canadians got the ball rolling last year with a letter suggesting talks on mutual recognition of ministries; last June, the American denomination’s General Synod voted almost unanimously to begin talks that could lead to full communion.

On the surface, the United Church of Christ and The United Church of Canada have many similarities. The Canadian United Church came into being in 1925 when Congregationalists, Methodists and Presbyterians merged. Evangelical United Brethren churches joined in 1968. The American UCC resulted from a 1957 union of the Congregational Christian Churches and the Evangelical and Reformed Church.

Both churches have elliptical crests and mottoes based on scripture from John 17:21. The Canadian version, in Latin, is translated as “That all may be one,” while the American church’s crest says, “That they may all be one.”

Talks between the denominations are expected to drill more deeply — into theology, practices, traditions and ministry. But because the two churches carry the call for Christian unity and ecumenism in their DNA, hopes are high on both sides.

Rev. Karen Georgia Thompson, ecumenical officer for the United Church of Christ, says the two denominations are “more alike than we are different.” But unlike other Reformed churches around the world that are united (created by a union or merger) and uniting (committed to ecumenism), they also share a geographical border.

About two years ago, with internal changes looming, The United Church of Canada began looking at closer ecumenical relationships and mutual recognition of ministry agreements with other denominations. With the American UCC, however, it’s heading directly into discussions about full communion — which would also include the exchange of ministers. That’s partly because the U.S. denomination has lots of experience in forging full communion relationships and partly because both churches sense they already have much in common.

The Canadian and American United churches were both created by organic union, where denominations leave behind their former identities and bring members and resources into a new church. In more recent history, those agreements have proven difficult. In Canada, a highly anticipated merger with the Anglican Church of Canada failed in 1975. Anglican-United talks resumed about 10 years ago and still continue, but union is unlikely.

Similarly, organic union talks between the American UCC and the Church of Christ (Disciples of Christ) faltered, but then changed tacks. The two denominations completed a full communion arrangement 25 years ago and have worked closely since then.

The United Church of Christ is also part of a full communion arrangement that includes three other U.S. denominations. Its website says, “Full communion means that divided churches recognize each others’ sacraments and provide for the orderly transfer of ministers from one denomination to another.” Co-operation among church officials is possible, but “it is above all in relationships between local congregations that agreements of full communion become alive.” In plain language, ministers and members can move freely, mission can be easily shared, but congregations, national staff, pension plans, fundraising programs and endowments aren’t disrupted.

For the American UCC and Disciples of Christ, full communion has brought shared regional offices and staff in one western Conference, plus a joint Global Ministries Board and overseas workers. Many ministers work across denominational lines. “So, there is a lot of energy around the relationship,” says Rev. James Moos, UCC executive minister for wider church work.

A Canadian-American relationship may be as significant for what it says as what it does, according to Rev. Bennett Guess, executive minister for local churches in the United Church of Christ. “Especially at a time when crossing borders of all kinds is made increasingly difficult, our willingness to express a commitment to be fully ‘one church’ is a powerful statement.”

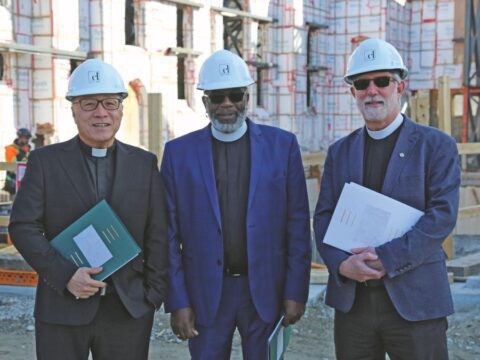

Rev. Bruce Gregersen, the General Council officer who heads the United Church delegation, says full communion would be “a visible connection, a visible commitment to union.”

But what is the United Church of Christ? For starters, it’s as American as roast turkey and pumpkin pie, with Congregationalist roots leading back to Pilgrim dissenters who arrived in North America as early as 1620. Evangelical Reformed churches included settlers and refugees with roots in the German, Swiss and Dutch Reformation.

Twice as big as The United Church of Canada, the American UCC has about a million members and 5,100 congregations. It’s lost 10 percent of its membership in the past five years, less than its Canadian counterpart.

With Congregational and Reformed roots, the United Church of Christ is strongest in the U.S. Northeast and Midwest. Pennsylvania alone has 600 congregations and accounts for four of the church’s 38 Conferences. The church is well-represented on the West Coast and in Florida but has few congregations in traditional southern American Bible Belt states.

One of the four staff who make up the Collegium, a group that heads the UCC’s national administration, Moos sums up the U.S. denomination as “a progressive, inclusive church oriented toward justice.” Guess, also part of the Collegium, lists the church’s “core values” as “listening for God’s continuing testament, offering extravagant welcome and changing lives.”

The American UCC and its Congregational forebears have a record of progressive moves. They had their first female minister in 1852 and ordained the first openly gay minister in 1972. It was 1936 before The United Church of Canada ordained its first woman, Rev. Lydia Gruchy, and 1988 before the church decided that “all persons, regardless of sexual orientation,” could be ordained.

Both Canadian and American United churches agreed to support same-gender marriage in 2005, and both denominations have programs to help congregations welcome lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. The United Church of Christ’s Coalition for LGBT Concerns has a team of four national staff working on its Open and Affirming program. About one-fifth of the church’s congregations are on board. The United Church of Canada’s Affirming program is largely led by volunteers and has been joined by fewer than five percent of United Church of Canada congregations and ministries.

There are also similarities in recent promotion campaigns. The American UCC program, called God Is Still Speaking, was used to brand the denomination as a progressive church whose theology is still evolving. A follow-up called Stillspeaking, with a large comma as its main symbol, is widely used and recognized. The United Church of Canada’s Emerging Spirit program funded a similar high-profile media campaign and also offered seminars on welcoming tactics, but has not had such a lasting visible effect.

In both United churches, congregations’ theologies range from progressive to traditional. Rev. Mark Toulouse is the principal of Emmanuel College in Toronto and an American who previously took part in UCC-Disciples of Christ full communion talks. He is now a part of The United Church of Canada delegation and says, “You probably wouldn’t see much difference” in the two church’s recently adopted theological statements. However, “just like The United Church of Canada, the spectrum of theology in the United Church of Christ is about the same” and ranges from conservative to “almost post-theist.” Pilgrim-St. Luke’s is toward the progressive end of that spectrum. McKay, who began serving the congregation 24 years ago after a stint in New York City’s East Harlem, calls it a “prototypical” United Church of Christ congregation, with its diverse, intercultural membership.

González, who was forced to leave the United Methodist Church after coming out as gay, took over leadership of the fledgling El Nuevo Camino congregation about a year and a half ago. Both he and McKay agree that the “typical” UCC congregation is probably older, less ethnically diverse, more middle class and with a more traditional theology than their congregations.

Pilgrim-St. Luke’s and El Nuevo Camino are “social media friendly” — mainly under González’s guidance — and have a gay-straight alliance group. But most of their other activities could be found in any United Church of Canada congregation: Christian education, Bible study, an after-school arts-based childcare program, women’s groups, choir, drama and book clubs.

Outreach programs at UCC churches across the United States often mirror those of their Canadian counterparts, including homeless shelters and food banks. Gun violence and gun control issues top the agenda in the U.S. United Church, while First Nations issues are a leading concern in Canada. But both churches are concerned with immigration and refugee issues, race relations and LGBT issues.

National staff from both denominations often meet at issues-related conferences, but Rev. Dan Hayward of the eastern Ontario Ingleside-Newington Pastoral Charge began building more local church connections a couple of years ago. Bicentennial celebrations for the War of 1812 provided the opportunity.

Hayward, then chair of Seaway Valley Presbytery, forged a cross-border partnership with the Black River/St. Lawrence Association of the American UCC, “to bring a church witness” to the bicentennial, “so it wasn’t all about battles and hostility.” There were exchanges of prayers and cross-border Presbytery and Association visits.

Now a member of The United Church of Canada’s delegation, Hayward says national talks “will add impetus to dialogue that is already taking place at a local level.”

With the United Church of Christ General Synod — which meets every two years — gathering next year at the same time as the triennial General Council meeting of The United Church of Canada, 2015 is an obvious but informal deadline for an agreement. Hayward is ready to start talking. On both sides of the border, he says, “I think we can learn a lot.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s February 2014 issue with the title “Cross-border church.”