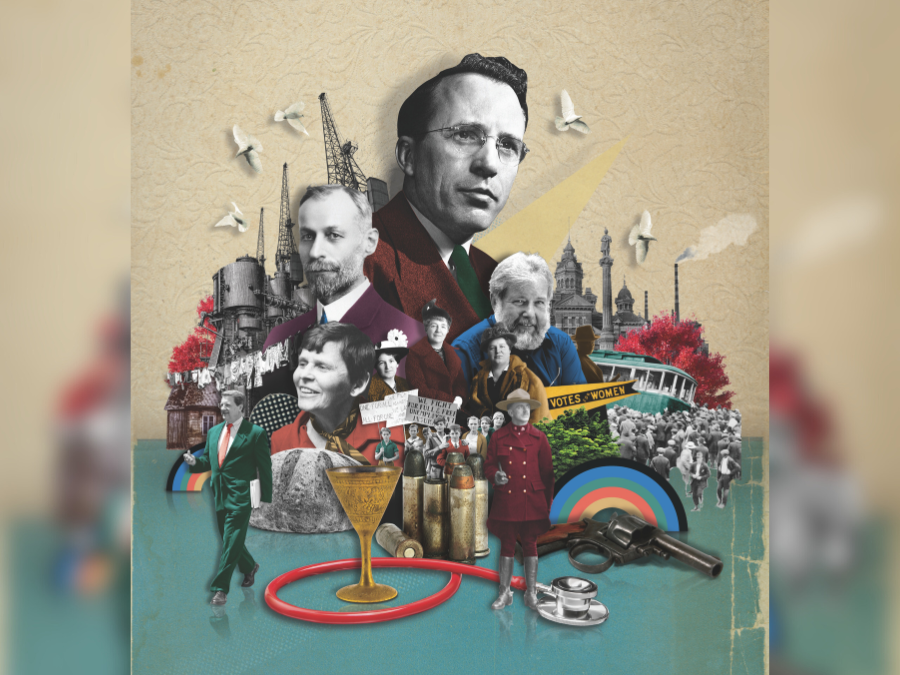

The flashpoint came on June 21, 1919, during the Winnipeg General Strike. Fed up with grinding poverty, 30,000 people — factory workers, transit workers, postal workers, even police officers and firefighters — had paralyzed the city for six weeks, demanding fair wages and the right to organize. Outside city hall, a peaceful protest erupted into violence when the Royal North-West Mounted Police, carrying clubs and revolvers and backed by hired muscle armed with baseball bats and hoe handles, charged into the crowd on horseback. Chaos erupted. Thirty strikers were hurt. Two were killed. The date has gone down in history as Bloody Saturday.

By nightfall, the protesters had scattered, and Rev. J.S. Woodsworth, a Methodist minister and leader in the social gospel movement, was arrested on charges of seditious libel for the crime of writing editorials supporting the workers’ cause.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

For the social gospel movement, the Winnipeg General Strike was a crucible moment. Born in the United States and United Kingdom from Industrial Age suffering and intellectual ferment, it confronted the harsh, Dickensian realities of immigrant slums, overcrowding, poor health and labour exploitation. Fuelled by throngs of disillusioned citizens, the grassroots uprising spawned a dynamic Christian left that transcended international borders — uniting clergy, teachers, doctors, labour activists, co-op organizers and others across the western world.

The movement caught on widely in Canada. Its leading proponents championed the cause before and after the strike from both pulpit and politician’s seat. Churches embraced a heightened sense of mission, seeking a government response to the profit-first nature of capitalism. Social gospellers, both within legislatures and beyond them, fought tirelessly for unemployment insurance, old-age pensions, universal health care and other measures.

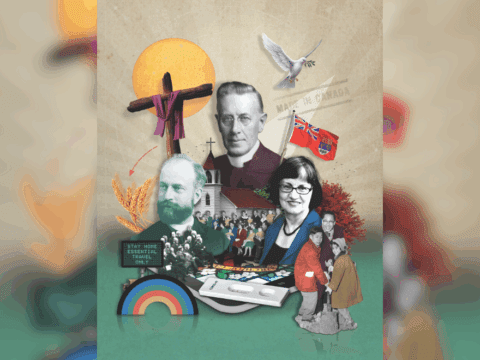

This growing synergy between faith and social activism paved the path for one of the most ambitious ecumenical projects in Canadian history: the creation of The United Church of Canada. The denomination was born on June 10, 1925, almost six years to the day after Bloody Saturday.

Canada’s new denomination, the union of Methodists, Congregationalists, most Presbyterians and others, was a direct expression of the social gospel. Its focus was to seek the kingdom of God on Earth through systemic policy change, says Rev. Ted Reeve, author of Claiming the Social Passion: The Role of the United Church in Creating a Culture of Social Well-Being in Canadian Society. “There’s an awakening of well-intentioned Christians: that [poverty] is a bigger issue than Christian charity can address,” says Reeve.

The social gospel’s heady mix of hope and determination flowed through Canadian society, becoming an ingrained, if unconscious, part of the national psyche. But by the late 20th century, the heft of the Christian left as a moral counterweight to conservative faith-based politics began to fade. “Most in the United Church, including ministers, have forgotten the context and origins of the social gospel movement,” says Rev. James Christie, professor emeritus of theology at the University of Winnipeg. Instead, some identify with what’s known as progressive Christianity. Rather than attacking the systemic roots of economic inequality, its priorities include liberal theology, anti-racism, ecological concerns, advocacy for poor nations and diversity, equity and inclusion.

Today, as economic inequality deepens, democracy falters, white Christian nationalism rises, the climate crisis grows increasingly urgent and the Christian left struggles to be heard above the din of angry voices, the heirs of the social gospel might take stock of the movement. Can this legacy continue to offer inspiration in the face of our own monumental challenges? Is it a blueprint for social transformation, or has it faded forever into irrelevance?

The turn of the 20th century shook Winnipeg, and all of Canada, to its core. A wave of immigration from across Europe redrew the social map while new technologies — electric lights illuminating factories; telephones and automobiles connecting distant towns — upended industry and everyday life. As the cost of living soared, poverty spilled into the streets, making it painfully clear whom the economy was really serving. In this turmoil, everything was up for debate: citizenship, community, church and state.

Into this mix stepped theology professor Rev. Salem Bland. Dubbed a “pioneer of progressive religion” in Canada by the late historian Richard Allen, Bland arrived at Wesley College in Winnipeg in 1903. A lifelong reformer, he blended temperance, sabbath observance and church-union advocacy with a sharp awareness of social inequity. He championed a Christianity that addressed real-world problems directly.

The turn of the 20th century shook Winnipeg, and all of Canada, to its core. A wave of immigration from across Europe redrew the social map while new technologies upended industry and everyday life. The cost of living soared. poverty spilled into the streets.

He was celebrated for that but also vilified. He “enraged” the city’s clergy and lay people, Allen writes, by calling out the hypocrisy of wealthy congregations when it came to matters of social justice. In 1920, when Bland released his socialist vision in a book called The New Christianity, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police secretly tried to sabotage its public reception in Toronto.

Bland’s ideas inspired a generation of social gospel leaders who criticized so-called bourgeois Christianity — too sectarian, too selfish — and advocated instead for an inclusive faith practice that would summon a new social order. This was Christianity in action, applying Jesus’ teachings head-on to the world’s injustices, says Christie.

For these radical social gospellers, the horrors of the First World War amplified the need to fight inequalities and injustice at home. Soldiers were promised jobs and health care after the war, for example, but the government failed to provide them, says Reeve.

The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike was a tipping point, proving how far some proponents were prepared to go in pursuit of social transformation. Among them were Woodsworth and Rev. William Ivens, two Methodist ministers who traded pulpits for picket lines. By then, both had lost their confidence in the institutional church.

Ivens, a maverick preacher, had been booted from the Methodist Church in 1918 after defending conscientious objectors and slamming war management in the press. When the church threw him out, Ivens founded the Labour Church, where his fiery sermons on workers’ rights drew hundreds of eager listeners.

Woodsworth, meanwhile, disillusioned with what he saw as the institutional church’s lukewarm response to social inequality, left the Methodist Church in 1918 to focus entirely on activism.

For both Woodsworth and Ivens, the strike lit a fire. Ivens, who edited the strike bulletin, was tried and jailed for seditious conspiracy — only to bounce back as an Independent Labour Party member of the legislative assembly. Woodsworth, ever the visionary, went on to lead the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) after a brief imprisonment, laying the groundwork for Canada’s social safety net.

More cautious social gospel leaders hesitated. The backlash against the strike was brutal; middle-class churchgoers were forced to confront the gulf between the Christian socialist view of the Gospel and the traditional salvation-oriented view. Many agreed that change was needed — but not at the cost of their hard-earned comfort or the church establishment.

Whether radical, conservative or somewhere in the middle, social gospellers began to see the story of Jesus through a new lens — not waiting for heaven after death but making one here on Earth. Paul the Apostle, the fiery, relentless missionary, was seen as a radical movement builder, Reeve says. Paul’s personal awakening had sparked an early Christian social revolution. For social gospellers, this was a blueprint for organizing a co-operative, equitable world where faith wasn’t confined to personal salvation but ignited tangible change.

As it was for Tommy Douglas. The strike had galvanized the future Baptist preacher and Prairie politician. Just 14, he was on a roof in Winnipeg on Bloody Saturday, watching as bullets punctured the air and killed a man on the sidewalk below. “Whenever the powers that be can’t get what they want,” he reckoned, “they’re always prepared to resort to violence or any sort of hooliganism to break the back of organized opposition.”

Douglas became a champion of the social gospel, advocating for policies that were as pragmatic as they were compassionate and fair. “He was part of this movement — the social gospel, practical Christianity — which really felt that part of an essential role of the church was to be involved in trying to make life more fair and more humane for people on Earth,” says his biographer Vincent Lam.

The push for progressive action drew in Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Anglicans and United Church folk alike, along with Catholics. Building on the groundwork of abolitionists and suffragists, social gospellers propelled the church, and the country, to the forefront of tackling the era’s injustices.

***

The social gospel was about calling governments to action and that meant some gospellers turned to politics to carry the torch of social reform. Woodsworth was elected to Parliament in 1921; Douglas followed him 14 years later. Both helped found the CCF in 1932. The fledgling party, which in 1961 would morph into the New Democratic Party (NDP), spearheaded policies inspired by the social gospel’s ideals. Its vision: a society rooted in justice, equality and social responsibility.

At its inaugural convention in Regina, the CCF introduced a manifesto that feels eerily relevant today, castigating private profit as the main stimulus to economic growth at the expense of the security of common people. It also called for a constitution, a charter of rights and transformative reforms such as national workplace standards, public health care, unemployment insurance and robust pensions — changes that would shape Canada’s future.

Douglas, then a Baptist minister in Saskatchewan, put his name forward as a CCF candidate only after he was told that his career in the church was cooked if he didn’t quit politics. “He had a very combative streak to him,” says Lam. “He’d been a provincial champion in lightweight boxing as a younger man…and when threatened by his superintendent, he told the guy, ‘You’ve just given the CCF a candidate.’”

The CCF’s goals tantalized many progressive Christians. Its creation gave the left wing of the United Church a natural political ally, and not a moment too soon. The optimism of church union in the 1920s was challenged by the scarcity of the Depression: resources dwindled, salaries were slashed and deficits soared. Meanwhile, the unemployed flooded soup kitchens and pastoral care was stretched thin as communities faced layoffs and despair.

In 1932, the United Church responded by creating the Commission on Christianizing the Social Order, headed by the retired University of Toronto president Sir Robert Falconer. Its mandate? Figure out whether the church needed to call for radical social and economic changes to bring about justice. Two years later, the group released an incendiary report. “It just blasts away at the abuses of capitalism, the rights of labour and the need for a different social order,” says Reeve.

The report didn’t go far enough for some. While certain members wanted a more cautious approach to softening the blights of capitalism, others wanted to topple the system. What everyone agreed: the church was called to be a prophetic witness to the social gospel.

Several United Church clergy felt compelled to correct what they saw as the failure of Christians to put flesh and bones on the dream of the social gospel. In 1934, calling themselves the Fellowship of the Christian Social Order (FCSO), they urged the church to acknowledge the reality of class struggle and to stand with the oppressed and exploited. Many of the group’s members joined the CCF. The influence of social gospellers grew. Still, as the 20th century advanced and the Second World War ended, social gospel theology came under scrutiny, challenged by a trend toward a theology that emphasized salvation.

***

Among the sharpest critics of the social gospel’s strident optimism was the American theologian Rev. Reinhold Niebuhr, a leader in the Fellowship of Socialist Christians. He took aim at the belief in reshaping society through human effort, arguing that such idealism ignored the unsavoury side of human nature and gave too little emphasis to the role of God in human salvation.

Niebuhr said liberal theologies glossed over humanity’s darker inclinations like avarice, envy and the urge for power. These weaknesses don’t disappear in groups — they grow. Collective self-interest and the drive for dominance often trample ethics, making groups far more dangerous than any one person. The best we can do, he argued, is make tough calls for the sake of democracy, knowing our shared life will always be flawed.

Niebuhr’s Christian realism gained traction during the Second World War. Confronting evil, he believed, required grim moral clarity. In his 1940 book, Christianity and Power Politics, Niebuhr reconsidered his earlier pacifism, cautioning that shunning conflict might pave the way for tyranny. This stance struck a chord as social gospellers confronted the stark evil of Nazism, forcing many of even the staunchest pacifists in their ranks to pivot. By 1939, Woodsworth stood as the sole voice in Canada’s House of Commons to oppose the country’s declaration of war — a lonely testament to the agonizing moral dilemmas of the era.

As international tensions escalated, Rev. Dietrich Bonhoeffer — a key figure in the Nazi-resisting Confessing Church in Germany — crafted an influential theology of action, championing a faith that demanded decisiveness. For his decision to resist Hitler, he was executed. “The church is the church only when it exists for others,” he wrote from prison in his final days. He insisted that Christian political choices be both provisional and concrete. Provisional, because they must remain open to revision, shaped by experience, context and even failure. Concrete, because vague principles are not enough; faith must take tangible form in the real world.

Douglas, an MP in Ottawa until 1944 when he became premier of Saskatchewan, took up the same urgent challenge, turning moral conviction into clear action. He resolved to confront Nazism’s horrors head-on. A visit in 1936 to Nazi Germany, where he’d attended a chilling Nuremberg rally, had left him with an alarming sense of Hitler’s capabilities. Still, he was deeply critical of wartime policies, balancing his resistance to fascism with concern for the devastating toll the war took on ordinary Canadians. From Parliament, he panned Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s deference to the British War Office, questioning Canada’s military autonomy. He took an unwavering stand against the internment of Japanese Canadians, a stance that drew sharp criticism — even from within his own party.

He criticized the postwar Versailles-like carve-up of Europe, rejecting the idea that global powers could divide the world as spoils. “The great powers,” he argued, “had no right to sit down and divide the world like a pie.”

While not a pacifist like Woodsworth, Douglas embodied the struggles of social-gospel Christians at the time: balancing peace and justice with the stark necessity of opposing global tyranny. His enduring question: how to care for the vulnerable, including soldiers, in war and its aftermath?

After the war, Canadians began to envision a brighter future and the CCF offered a bold plan: proactive economic policies designed to benefit everyone. Major reforms, like a universal pension scheme, emerged gradually, driven by persistent CCF campaigns over the next two decades. (Only in 1968, after relentless pushing by the NDP, would universal health care come into existence across Canada — and never, says Lam, in the fullness Douglas had hoped.)

Postwar optimism extended to faith as church attendance surged and families grew, particularly in burgeoning suburbs where new congregations flourished. While traces of the social gospel remained, its prophetic voice grew fainter in this era of postwar affluence, drowned out by the hum of comfort and conformity.

***

Retired politician, academic and elder statesman Lloyd Axworthy was born mere months into the Second World War, his early years shaped by the hardships of a family and community grappling with the war’s far-reaching effects.

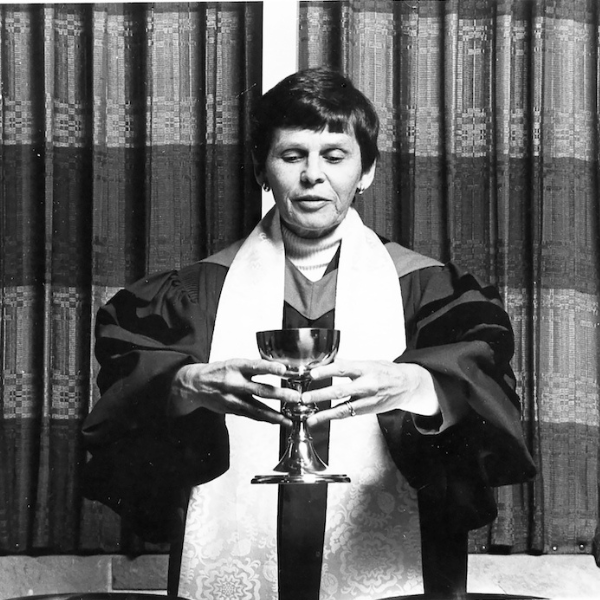

Growing up in the north end of Winnipeg — a hotbed of social-gospel politics and a medley of classes, cultures and ideas — Axworthy attended Atlantic Avenue United, a small congregation-led community. There, Revs. Roy and Lois Wilson made a lifelong impression on the future foreign affairs minister. Very Rev. Lois Wilson later became moderator of the United Church. “Roy and Lois brought to that small church in the north end an incredible sense of what the social gospel meant in practice,” he says.

It meant an absence of hierarchy; it meant engagement; and it meant, for the future statesman, the first stirrings of political consciousness. Axworthy began to see democratic channels as a tool for addressing the disparities he saw all around him, including anti-Ukrainian prejudice.

At Princeton University in the early 1960s, he was captivated by the call of the civil rights movement. On March 24, 1965, he joined the historic March to Montgomery, a 25,000-strong procession led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. It was an epiphany, Axworthy recalls — a spiritual awakening and a profound act of Christian witness.

His social gospel upbringing underpinned his historic decision as foreign affairs minister for Prime Minister Jean Chrétien in the late 1990s to support a U.N.-led humanitarian offensive against Slobodan Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. It also contributed to his advocacy to ban land mines. For him, politics wasn’t a quest for power but for justice. Blending Niebuhr’s Christian realism with his own social-gospel pursuit of God’s will on Earth, he saw the darker forces behind the campaigns for power — and rallied to quash them.

When Lois Wilson became a Canadian senator in 1998, Axworthy called on her to tackle two urgent international crises. First, he sent her to Sudan to investigate allegations of Canadian oil companies’ complicity in the bombing of rebel groups. Then, she went to North Korea to foster dialogue with the isolated regime.

These missions exemplify a deeply rooted Canadian tradition: religious and political leaders stepping onto the global stage to address issues of justice and diplomacy. Figures like Woodsworth and Douglas, and later Axworthy and Wilson, showed how faith-inspired ethics could inform global common causes, shaping everything from humanitarian aid to peacebuilding. A renewed energy fuelled participation in ecumenical justice coalitions, inner-city missions and even traditional politics.

More on Broadview:

Rev. Bill Blaikie, a social gospeller born into a working-class Winnipeg family, first rolled up his sleeves as an MP in the House of Commons in 1979, joining other Christian clergy in the NDP caucus. At the time, many in the party still espoused the social gospel tradition of Douglas and Woodsworth, championing the trinity of faith, justice and equality.

For Blaikie, ordained in the United Church, the power of this tradition lay in its witness to Jesus’ revolutionary critique of the market as ultimate authority. His youngest daughter, Tessa Blaikie Whitecloud, says her late father often lamented how Christians had missed the essence of Jesus’ message: the rich must sacrifice their profit.

“It’s about building a society of equality. It’s about building a society of care. It’s about being as compassionate to everyone we meet as Jesus would have been,” she says.

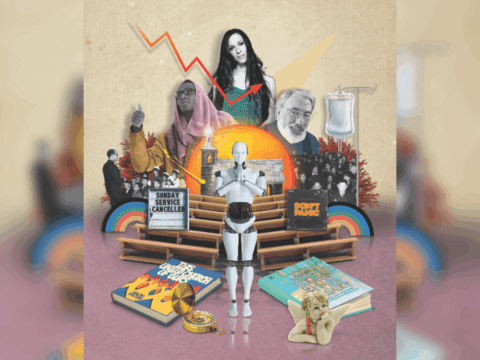

As a new century dawned, the influence of the Christian left in politics began to fade. Secularization and shifting priorities — including what Blaikie viewed as a focus on identity politics over social and economic equality — factored into this decline. In the past, the social gospel had challenged capitalism from a Christian perspective, but by the 2000s, religion in politics faced widespread skepticism. When Canadian Alliance leader Stockwell Day entered the national spotlight in 2000, his religious-right beliefs sparked intense media scrutiny and public debate over the role of faith in the public sphere.

Yet, as Blaikie points out in his memoir, progressive Christians like him were overlooked, their faith-driven politics dismissed. With religion still woven into Canada’s cultural fabric, believers must find their authentic voice in public life, he writes in The Blaikie Report: An Insider’s Look at Faith and Politics. “It is impossible — and in my opinion undesirable — to banish religion from the public or political spheres.”

Around this time, faith-based participation in justice coalitions for Indigenous rights and environmental protection, a remnant of the social gospel, was also fading. Many ecumenical efforts had either diminished in scope or been absorbed into broader advocacy movements. It’s part of the story of the withering of the Christian left that continues to this day.

***

More than a century after Bloody Saturday, does the social gospel have anything to offer progressive Christians today? Its history is both a cautionary tale and a call to action. The social gospel’s early successes led many to believe that public institutions had absorbed Christianity’s moral mission, dulling the urgency for activism, says American theologian Diana Butler Bass. As a result, the Christian right seized the narrative, and “the loudest, most corrupted versions of Christianity are now the ones being identified with Christianity as a whole, and that has left other Christians in this terrible place.”

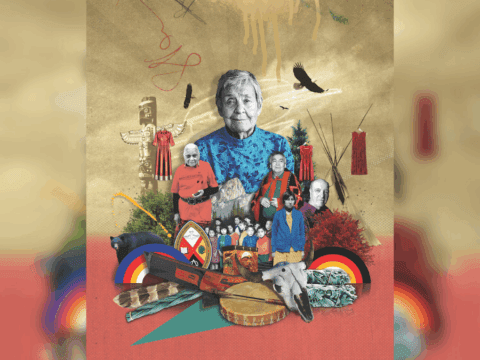

In addition, the social gospel’s legacy, while rich, is flawed. Its proponents were mainly white and middle class, led by men. Douglas briefly embraced eugenics in cases of those with intellectual disabilities or incurable diseases, and The United Church of Canada ran residential schools that inflicted lasting harm on Indigenous communities. Rev. Néstor Medina, professor of religious ethics at the University of Toronto’s Emmanuel College, says the legacy of colonialism has left a “major scar.” But he insists the social gospel tradition “can — and must — be celebrated.”

The history of the social gospel is both a cautionary tale and a call to action. The social gospel’s early successes led many to believe that public institutions had absorbed Christianity’s moral mission, dulling the urgency for activism.

Rev. Alexa Gilmour, a United Church minister and newly minted NDP member of the Ontario legislature, agrees: “We have to be careful not to throw away the [social] gospel just because we sometimes got it wrong.”

Today, progressive Christianity — a term that emerged in the United States later in the 20th century to describe those whose faith was influenced by social justice and theological diversity — often focuses on liberal theology and initiatives to promote diversity, equity and inclusion. While these are vital, the bold, systemic critique of power and care for the poor that flowed from the gospel has abated. Medina calls it a “historical amnesia with regards to the legacy of the social gospel in Canada.” The marginalized still suffer, inequality persists and the planet cries out for justice.

The social gospel needs new champions, Gilmour says. She points to figures like Blaikie, Wilson and former United Church moderator (and current Broadview board member) Mardi Tindal as models of courageous discipleship. Rt. Rev. Mariann Budde, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington who pleaded with U.S. President Donald Trump for mercy in a sermon in January, is another.

But for the social gospel to regain traction, it must be rethought, reconsidered and rearticulated for our times, Medina says. “How we understand God, Christ, Christianity, the faith — all of those things have changed and are changing in our current context.”

We live in perilous times. Queer and trans rights are vanishing, governments are fawning over fascist ideologies and misinformation masquerades gleefully as truth.

The social gospel’s message is both hardy and fragile, Gilmour says. “It’s like the light. If we aren’t holding it aloft, the world goes dark.” The task is to build communities of care, stand in solidarity and confront the dehumanizing forces that threaten our collective well-being. “We must hold one another and stand in the breach.”

Are we up to the task?

“Courage, my friends,” Tommy Douglas once urged. “’Tis not too late to build a better world.”

***

Julie McGonegal is a journalist in Elora, Ont.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s June 2025 issue with the title “Christian Changemakers.”