A swaddled baby boy is placed in a floating vessel by loving parents who, fearful for the baby’s life, send him away in desperate hope he’ll be found and raised by others. Their faith is realized. Not only does the sent-away son grow up in safety, he comes to personify justice and freedom while developing supernatural powers he uses to save people from danger and oppression.

This origin story was told millennia ago about Moses in the Book of Exodus. It was also retold 81 years ago as the origin story of Superman, the first superhero, in Action Comics #1.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

That’s no coincidence — our sacred stories have provided a foundation for superhero mythology ever since Jewish artists and writers first invented the genre in the 1930s. “Underneath all the sophistication of modern comics, all the twists and psychological drama, good triumphs over evil,” Jack Kirby, one of those original creators, has been quoted saying. “Those are the things I learned from my parents, and from the Bible.”

Today, with superhero movies dominating the summer blockbusters and comic book sales enjoying a renaissance, a new generation is immersing itself in these stories of ordinary people doing extraordinary good with the help of special powers. While not all of today’s superheroes openly practise a faith, religious themes have become more common and more explicit in comics, and religious representation is becoming more diverse, too.

In the beginning, though, the faith lives of superheroes and the Jewish backgrounds of their creators were mostly obscure, a subtextual web of references and implicit identities that flew under the radar in a time of widespread anti-Semitism.

More from Broadview: Cree filmmaker wants a Barbie that looks like her

The creators of Superman, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were both children of Jewish refugees who’d fled the Russian pogroms of the early 20th century and immigrated to North America. When they created Superman — an alien refugee from a dangerous planet — in 1938, they were likely drawing on both the Torah and their own families’ fiery exodus from Europe.

The Siegel and Shuster families did their best to assimilate and downplay their differences, altering their names so they sounded less Jewish — essentially adopting secret identities. These double lives were not unlike that of Superman, an Übermensch with a Hebrew-inspired name, Kal-El, masquerading as a schlubby reporter and Methodist named Clark Kent.

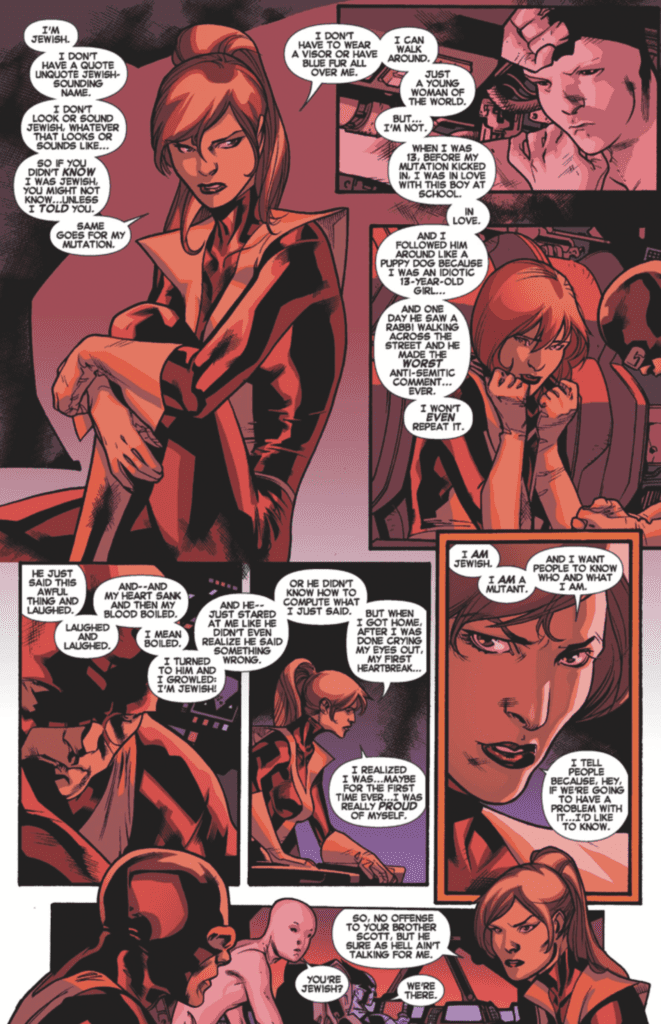

The first openly Jewish superhero, Kitty Pryde, was introduced to the Marvel universe in 1979 wearing a Star of David necklace. But the Jewish identity of other heroes continued to be hidden in plain sight. The Thing, a man made of rocks created in the 1960s by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby — real names Stanley Lieber and Jacob Kreutzberg — was a comic-book take on the golem, a creature from Hebrew folklore built of earth and brought to life though kabbalistic mysticism. While many managed to read between the lines to recognize The Thing was Jewish (his alter ego was Benjamin Jacob Grimm, who came from New York’s Lower East Side, after all), it wasn’t until 2002 that he’d explicitly acknowledge his identity. “It’s just … I don’t talk it up, is all,” Grimm says when a friend brings up his faith. “Figure there’s enough trouble in this world without people thinkin’ Jews are all monsters like me.”

Christian superheroes, of course, have never had to hide their faith in the same way. Introduced in 1964, Daredevil is a crime-fighter in a horn-cowl costume from New York’s Hell’s Kitchen. But those devilish signifiers are contrasted by the character’s devout Catholicism — he considers his superpowers divinely gifted, his vigilantism a service to God. And his most famous storyline (from 1986) concludes with his alter ego, Matt Murdock, discovering his long-lost mother is a nun.

In his comic book adventures and in the three-season Netflix series that concluded last year, Daredevil lives out a complicated faith. “I’m not seeking penance for what I’ve done, Father. I’m asking forgiveness … for what I’m about to do,” Murdock confesses to his priest in the first scene of the Netflix adaptation. In superhero culture, as in religious scripture, we meet characters who wrestle with the moral messiness of being alive, often relying on faith to guide their choices.

In recent years, this world has finally expanded to included Muslim superheroes. Sooraya Qadir, a mutant from Afghanistan code-named Dust, was introduced in late 2002. While some readers appreciated the representation, others argued her character relied too heavily on stereotypes — her power is to turn into sand, she’s rescued from sexual slavery by white men, and she speaks Arabic despite Afghanistan’s official languages being Dari and Pashto. As well, the overly sexualized way she was sometimes drawn led to a small scandal last year.

Other Muslim superheroes followed Dust, sparking positive headlines alongside right-wing backlash, but they were all minor characters. That changed with Ms. Marvel, who became the first Muslim superhero to headline a book in 2014. Kamala Khan, Ms. Marvel’s alter ego, is a Pakistani-American teen from New Jersey, and her Islamic identity is just as important to her story as her body-morphing superpowers.

In superhero culture, as in religious scripture, we meet characters who wrestle with the moral messiness of being alive, often relying on faith to guide their choices.

“It was really important for me to portray Kamala as someone who is struggling with her faith,” co-creator G. Willow Wilson told the New York Times in 2013. “It’s about the universal experience of all American teenagers, feeling kind of isolated and finding what they are,” she said, just shown “through the lens of being a Muslim-American.”

The Ms. Marvel series has sold over half a million collected editions, and Wilson has gushed about “the emails and the messages that [she gets] from comic book retailers who are really excited when girls in hijabs come into their store and ask for Ms. Marvel.” Now, the hero’s profile is likely to rise even more: Marvel Studios has hinted that she will play a significant role in an upcoming film.

But Khan has already ascended to a symbolic status for many — her image has been featured on signs protesting U.S. President Donald Trump’s travel and immigration bans, for example. To her fans, Khan is an embodiment of justice. And to Wilson, she is an example of the “neat ideological overlap” between superhero culture and religion, both of which concern “holding yourself to a superhuman ideal, doing good when it’s not required of you.” As her presence at protests makes clear, Khan has the same power to inspire action as a figure from scripture.

Superheroes like Ms. Marvel and Daredevil have become the dominant pop culture force of our time, even as many of them embrace their religious identities. Like the faithful heroes we meet in the world’s religious scriptures, these larger-than-life figures offer deliverance from evil and draw meaning from conflict to better themselves in the here and now.

In these fraught and uncertain times, it is perhaps unsurprising that readers and viewers are turning to these characters and the allegorical worlds they inhabit, where invisible forces of good move among us.

This story first appeared in the September 2019 issue of Broadview with the title “Caped crusaders.” For more of Broadview’s award-winning content, subscribe to the magazine today.

But still, what does it matter if a superhero film leaves the audience feeling inspired? It seems unlikely that we will need to use that inspiration to fight off an imminent alien invasion. Instead, it is important because it builds us up for the little battles we face in our daily lives. If Batman can deal with not being able to save Rachel Dawes, one can certainly survive being stood up for a date. If Superman can sacrifice himself to save everyone on Earth, a football fan can skip watching one game to help a friend in need. And if the Avengers can figure out how to work together long enough to save the world from alien invasion, coworkers who dislike each other can power through a joint project for the sake of the work at hand. Where a viewer finds common ground with a superhero they find a source of strength, of courage, of inspiration. People walk around wearing Batman shirts, drinking from mugs emblazoned with Captain America s emblem, collecting little vinyl figurines of their favorite heroes. Doing so reminds them that these heroes deal with the human realities running rampant in their own lives, a comforting thought for many an audience member.