Q After five years of work, how do you feel about the end result?

A I think I feel a state of consolation. It’s really been helping me. It began as an outgrowth of the spiritual direction program [at Regis College] I was taking. My classmates said that what I was doing is a ministry, and I said: “But I’m retiring. I’ve had enough of working with pictures. I want to work with people.” And they said, “but there is still something you have to do.” I listened. And I thought: “Why couldn’t the artists be the spiritual directors? Why couldn’t the visitors and viewers be the directees? Why couldn’t the paintings be the media through which an exchange takes place because these pictures are the attempts by the artists to convey their mystical experiences?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Q Is spirituality a part of the reason why some of the pieces are so popular?

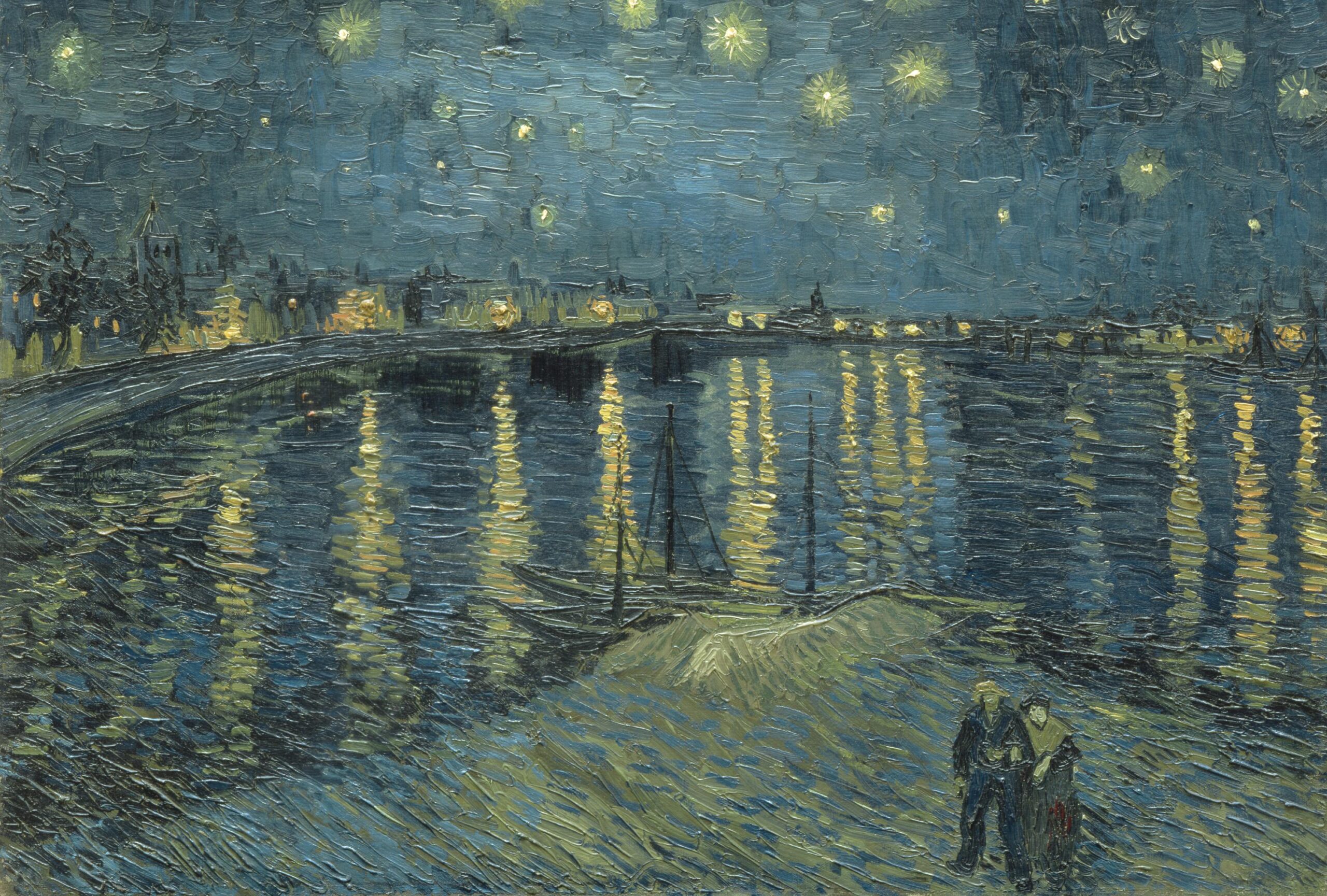

A People gravitate to Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night by the millions and spend hours of contemplation in front of Oscar-Claude Monet’s Water Lilies. Art historians tend to say the fame is the result of reproduction and publicity. But for a very long time, I’ve suspected that it is quite different. These pictures were really providing nourishment. I think works of art have had the power — since the beginning of the Christian tradition — to convey and to evoke spiritual states. We’ve kind of lost the ability to read them because in preliterate times, altarpieces performed that function. With the Reformation and iconoclasm, altarpieces disappeared but artists continued to find in art an outlet for the spiritual, often using secular imagery.

Q Why do you think we are only now viewing these pieces through a spiritual lens?

A I think that we, art historians, have been trained to look at early modern art in a secular way. So what I’m doing — and what our colleagues are doing — a lot of people would find very difficult to swallow in our field. They would think we are reading into works of art — like we are making stuff up — and that is considered to be almost verboten. Therefore, it has been important to us to investigate the spiritual journey of the artist to the best of our ability. So, for example, Monet’s water gardens were a motif for personal contemplation. His friend wrote that he would spend up to six hours just sitting in contemplation in front of them. His contemporaries saw that [spirituality] in his pictures, and he didn’t say, “No, that’s not true.” It’s astounding that we can bring these pictures to life, as the artist intended, but in the way that no art historian would have wanted to.

Q In the mid-19th century, the power of institutional religion was challenged. Secularism and rationalism rose. Do you see similar attitudes toward religion today?

A Very much so. It’s one reason why I thought it was timely to do this. We all know that we need religious institutions. We also know that because they are institutions, and they are certainly not at arms length from political, social and economic structures, they can be hijacked. I’m not sure that I’m seeing spirituality as being the main concern of religious institutions these days, and I think people are starving for the spiritual. So even though I go to church as part of my practice, I totally understand people who don’t go near churches — except when they are on holiday — but who are very much engaged in the spiritual. I think that we don’t know how to deal with this. In this exhibition, we are inviting people to think about the place of spirituality in their own lives.

Q Can you describe the response?

A It’s been a phenomenal response. Every week, the attendance gets higher. Now, we are realizing that noise disturbs people here. It’s really become a sacred space. I think we are going to put up signs asking people to be quiet. I have observed people from all walks of life, including people struggling with disabilities, coming in droves: a woman with a white cane was in front of the Monet for hours. A child with Downs Syndrome was riveted by Georgia O’Keefe. This isn’t our usual first audience. People are definitely having experiences they didn’t expect. I think we are on the cusp of something quite fascinating. I don’t think any of us quite know what it is. We’re encouraging people to come through this exhibition with the idea of walking with the artists on their journeys and thinking about the role of the spiritual in their lives. And I think that people are doing just that.

This interview has been condensed and edited.