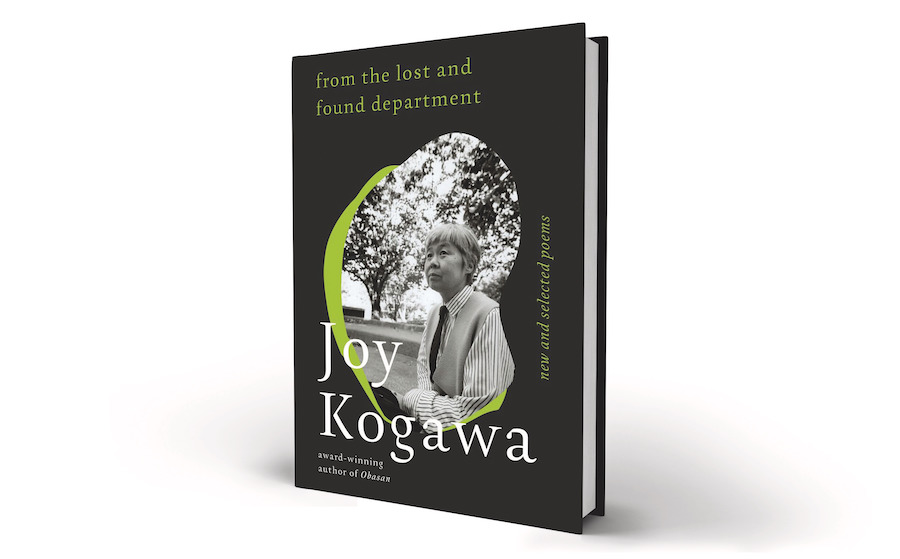

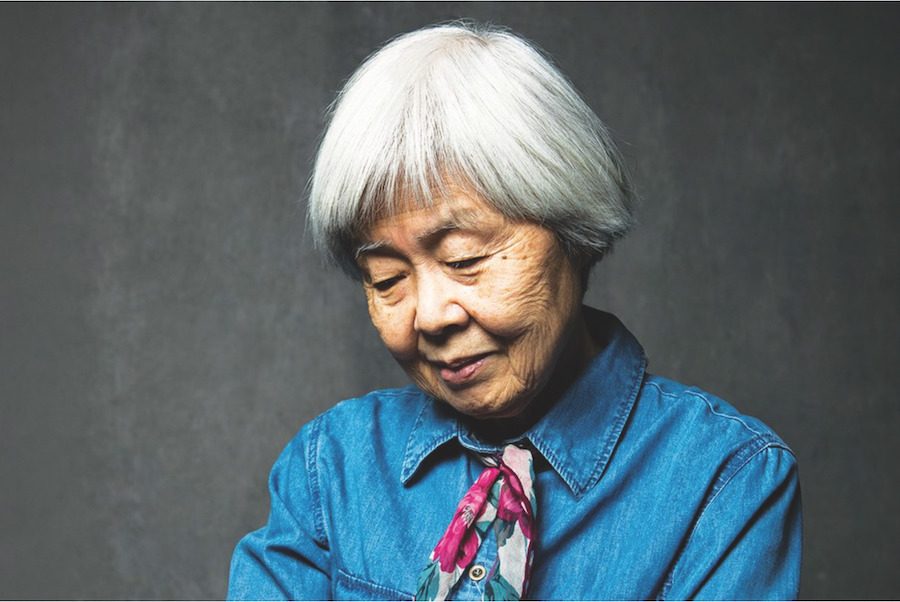

Canadians know writer Joy Kogawa for her celebrated 1981 novel, Obasan. Drawing on her own history, the book shines a light on the unjust internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War. But poetry was Kogawa’s first love, and it might also be her parting gift to the world. Now 88, she has released what she calls her “last hurrah.” From the Lost and Found Department is a collection of revelatory poems about suffering and compassion, heartache and forgiveness. In this conversation with Julie McGonegal, conducted over email, she reflects on her spiritual journey as the daughter of a defrocked Anglican priest and as a human being searching for truth and love.

JULIE MCGONEGAL: One night in Japan many years ago, you were visited by two words: “mercy” and “abundance.” How do those words shape this collection? What others join them?

JOY KOGAWA: As I remember that event, the words arrived as a single and singular gift, the two words as one, indivisible, their meaning contained in their togetherness — like “truth” and “love” a oneness, a unit of meaning. Truth without love is not truth, and love without truth is not love. Likewise mercy and abundance. When we are in need of mercy, as we are today facing climate change, may Mercy arrive in huge waves into our fragile, proudful, unseeing condition.

More on Broadview:

- “Reuniting with Strangers” explores the complexities of reconnecting Filipino families

- New documentary explores intimate connection between grief and art

- ‘Riceboy Sleeps’ explores the burden of belonging

JM: You were raised the daughter an Anglican priest, and you have described yourself as moving from a fundamentalist Christian position into something more deeply reflective. Can you tell me about that journey and where you find yourself today?

JK: Fundamentalism and literalism go together in my mind, and somewhere along the way, the ascendancy and primacy and rigorousness of love as the highest priority can be abandoned. I remember reading a Jewish dictum that said, “Where the laws of God are in conflict with the wellbeing of people, the well being of people shall prevail.”

[My spiritual path] has been unpredictable and is attended by surprise and gratitude. There seems to be a sense of undeserved gift. It’s as if a door is opened from the other side and a shaft of light appears. This kind of thing appears to be shared throughout history, and when we experience it we can recognize the “aha” that countless others have known.

JM: In recent years, your father’s history as a pedophile has come to light. He sexually abused many children through his work as a priest. What does it mean for you to hold the tension between loving someone and recognizing that they have done much harm?

JK: My dad once said to me when I was writing The Rain Ascends, which is about a priest who was a pedophile, that he wished I would write about the good things he did. I replied that God required us to speak truth. Dad then said, “If God is telling you to write truth, then you must do it the best you can.”

He was Jekyll and Hyde, and as a child I adored him, not knowing there was a dark side. The truth is he was both.

We become what we behold. Those who only see the dark are in danger of becoming the dark ness that is condemned.

JM: Your work has been lauded as a cultural touchstone for Canadians. As you look back at your literary career, what do you hold up and cherish? What, if anything, do you regret?

JK: I’m amazed that my novel Obasan has become a classic. And that, at this age, a book is forthcoming. My last hurrah. I am more than grateful for this blessing and hold it like a soap bubble in my slippery astonished hands.

As for regrets? Hmm. I rarely think about regrets. My kids did not have a normal cookie-baking mommy, but what a lot of love we have.

Want to read more from Broadview? Consider subscribing to one of our newsletters.

JM: How has the field of CanLit changed since you came onto the scene as the first Japanese Canadian novelist to gain recognition in this country? How have you witnessed publishing in this country change, in your time, for racialized writers?

JK: I think it’s been a while since the assault on white male dominance in the arena of writing, and there’s been a lot of headway into multiracial, gender, ethnic, sexual variety. The not yet seen or heard are alive and active in their many corners, and technology assists in democratizing. I’m more or less at the “letting go” stage and often see these as the best years of my life.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

Julie McGonegal is a writer and editor in Guelph, Ont.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2024 issue with the title “Joy Kogawa’s ‘Last Hurah.’”

Thanks for reading!

Did you know Broadview is the only media organization in Canada dedicated to covering progressive Christian news and views?

We are also a registered charity and rely on subscriptions and tax-deductible donations to keep our trustworthy, independent and award-winning journalism alive.

Please help us continue to share stories that open minds, inspire meaningful action and foster a world of compassion. Don’t wait. We can’t do it without you.

Here are some ways you can support us:

Thank you so very much for your generous support! Together, we can make a difference.

Jocelyn Bell, Editor/Publisher, CEO and Trisha Elliott, Executive Director

Comments