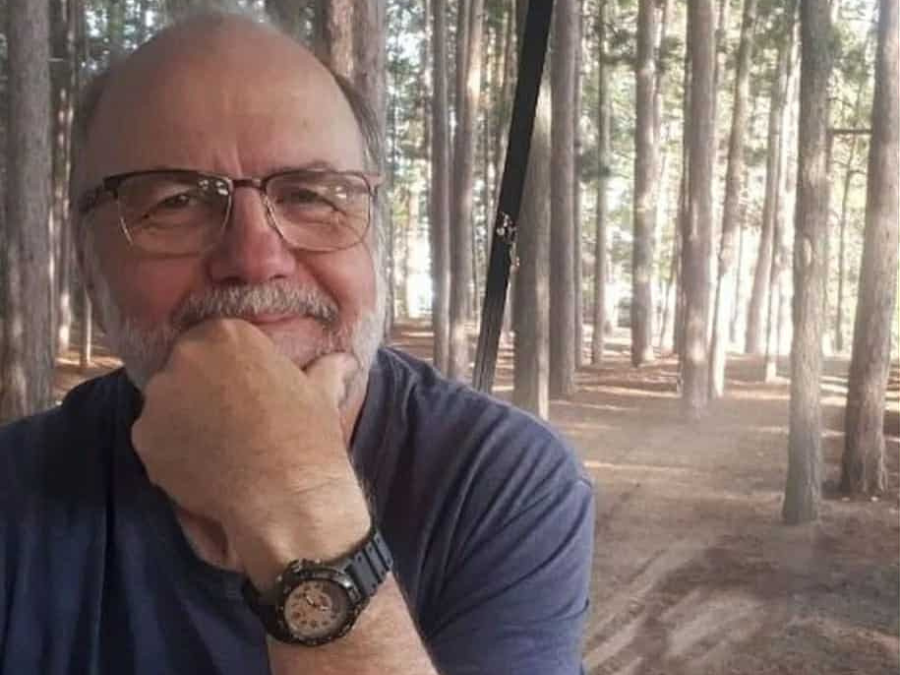

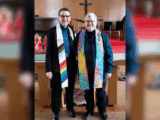

Rev. Grant Dillenbeck and I met in 1987 when we were both at our settlement charges in Southern Alberta and have been friends ever since. Dillenbeck was diagnosed with stage 4 terminal pancreatic cancer last year and being him, he wanted the end of his life to make a difference to others, so here is our last conversation.

Christopher White: Good morning. Grant, it’s good to see you. How are you doing?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Grant Dillenbeck: Today is not a bad day. My pain level is low. My cognitive awareness through the different medications is pretty good. It’s not a bad day in the grand scheme of things. And it’s especially good to be able to share with you.

CW: So tell me about what’s happened?

GD: I had my first symptoms of something going on urologically in September 2024. The doctor said it could be any number of issues, and it took until December to actually get a diagnosis of stage 4b adenocarcinoma of the prostate. For those who are not medical people, that means a very advanced and spread cancer. So I have it in my bones, I have it in my lungs, and it’s starting to spread to my liver.

It’s a cancer that they said very early on is not curable, but it’s going to be dealt with in more a palliative approach. When I met with my urologist after the first scan, the first words he said were “the shit has really hit the fan.” I was scared, and I kind of said “it’s all over now,” — my old life was all over.

CW: So from that moment on, you were dealing with your own mortality?

GD: Absolutely. And that’s certainly happened right from day one of seeing the scan and hearing the diagnosis. It definitely put my life in a different perspective. How do I deal with a sense of diminishing capacity, both physically and mentally? I’ve always been a doer. I’ve always been the guy that worked 60 to 70 hours a week, that says, “no, I don’t need help. I’m here to help you.” I’m wearing my Algonquin Park T-shirt today. Just four years ago, I did the longest marked portage in Algonquin Park, and now I don’t even think I could walk into my backyard. I really think that for people in general, but especially for clergy, we don’t think about that happening.

And so my hope today is to be able to offer some suggestions, insights, experiences, to say what might people be able to do to be prepared for this sudden onset of diminished physical and or cognitive capacity.

CW: Based on your experience, how can we prepare, when none of us honestly want to?

GD: “There are three areas I want to touch on.

The first is what I’m referring to as Circles of Care. We’ve developed Circles of Care in terms of emotional and pastoral support. We’ve developed Circles of Care in terms of helping with the yard work and all the stuff that needs to be done around the house. We have developed Circles of Care in terms of people providing food.

And you should have a Circle of Care in terms of the health care system, because most people move into this without having any clue how things work. Ask questions of your medical team and don’t go alone. Part of creating Circles of Care means building lists of people and asking: “would you be there to help me with this or that, if the situation arises?” And I kind of did a count this morning and we have about 50 people in my Circles of Care who will drive me to the hospital, who will come over for a visit and bring me Tim Hortons, who will pick me up off the floor if I fall.

Number two for me has been to appreciate the simple pleasures. I can sit here in my beautiful sunroom again, watch the birds at the feeder, appreciate the simple things, like a cup of coffee.

And this last one is one that you can’t necessarily force to happen, and that is to live in a relationship of unconditional love. And I have been so blessed to have a loving relationship with my wife, Ruth Richardson. She has been a tremendous support, physically and professionally, in terms of nursing and all that sort of thing, but just in terms of the love that we have shared and still share. That has been the greatest source of strength for me.

CW: Both of us have preached countless funerals about the presence of God through death. Where are your thoughts now on this?

GD: My sense of mortality is not just going from life to death but living in the midst of life and death and appreciating the blessings that I have had and continue to have in life, but also recognizing the grief, the uncertainty and the pain of entering into this different phase.

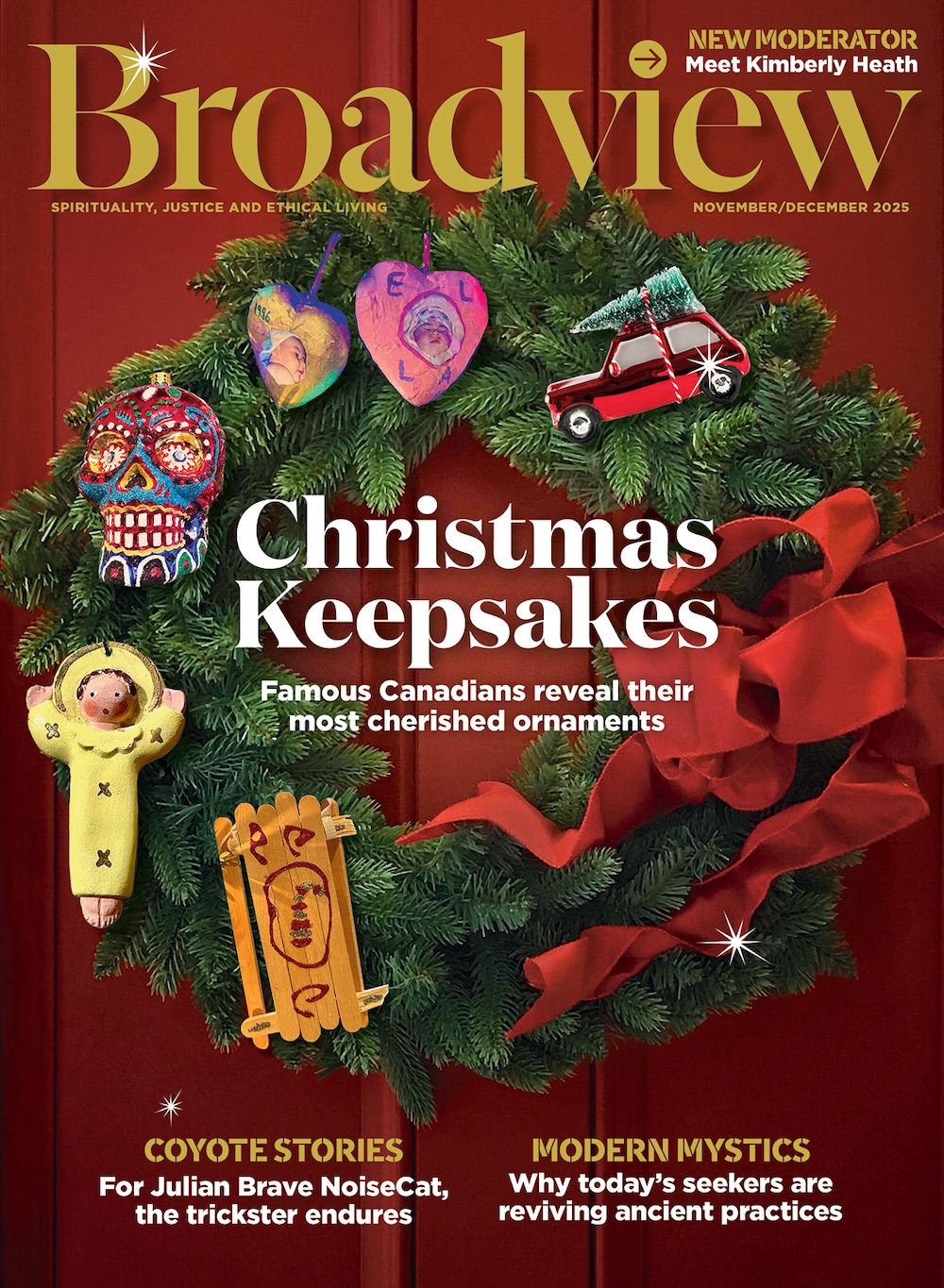

More on Broadview:

- In Oscar nominee Julian Brave NoiseCat, the trickster endures

- How memorizing the Gospel of Mark helped me grieve my wife’s death

- After learning of the death of his son, a bereaved father made a stunning phone call

CW: I have long held that when the time comes and I go to God, one of the things I’m going to say is “What the hell?” “Do you consider this good management?”What do you think you will say to God at that time?

GD: That’s a good question, a big question. I think there is a sense in which whatever it is that we have carried in this life, we do carry into the life to come. And so a part of that will be questions. A part of that will be, what the hell?’ But a part of that will also be, “it was amazing. It was incredible”. There would be nights I would be sitting in the hot tub looking at the stars, thinking, “if this was the only five minutes of experience that I ever had. It’s enough. It’s more than enough.” I’ve had a great life.

***

My friend Grant Dillenbeck died less than a week after this interview and I miss him.

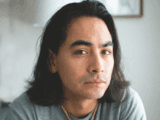

Rev. Christopher White is a United Church minister in Hamilton.