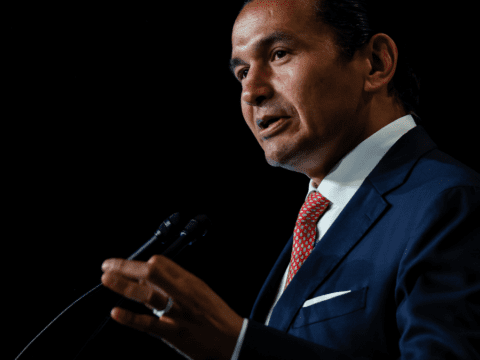

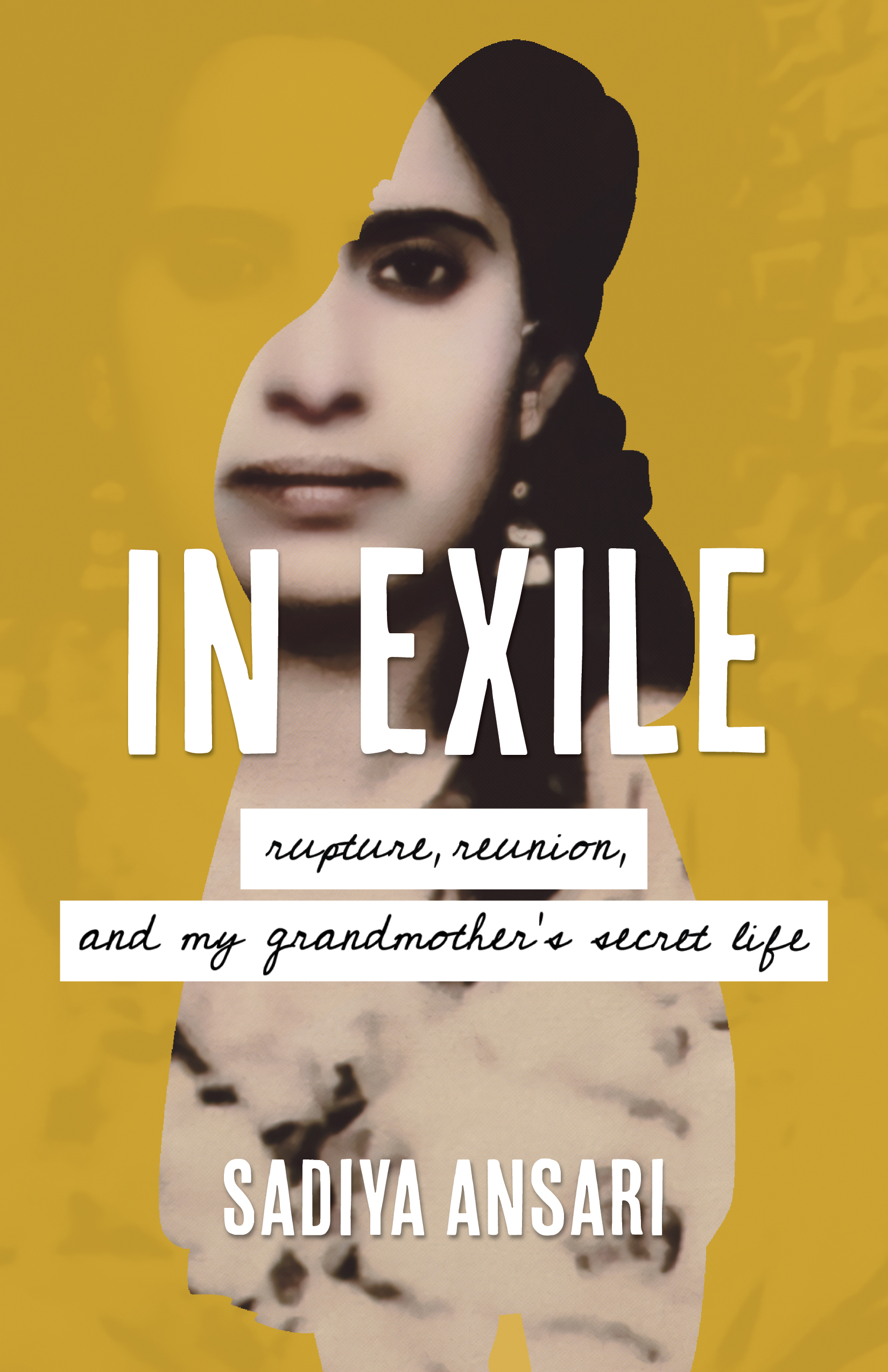

For seven years, award-winning Canadian journalist Sadiya Ansari reported from three continents to uncover a century-old family secret, culminating in her debut book, In Exile: Rupture, Reunion, and My Grandmother’s Secret Life. Her investigation looks into why her grandmother (Daadi) left her seven children to follow a man from Karachi to a small village in Punjab — a man whom she eventually also left. Ansari wanted to understand who her grandmother became when she was neither a wife nor a mother. But this, eventually, led her to another question: What opportunities exist for women who defy traditional norms?

In her book, Ansari uncovers the reality of her grandmother’s life and confronts harsh historical truths: the commonness of child marriages, the displacement of millions during Partition, and how the freedoms attained in 1947 did not translate into meaningful changes in the lives of women.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

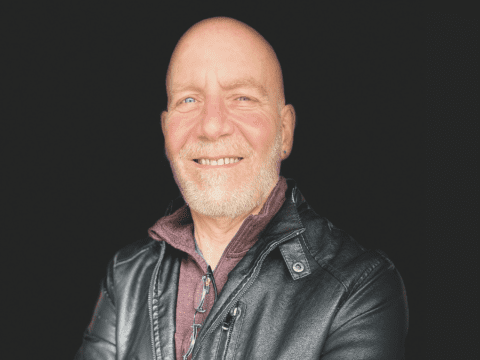

Sheima Benembarek spoke with Sadiya Ansari about writing personal narratives and the role of women in the Desi community.

Sheima Benembarek: In the book you write that growing up “is arriving at the understanding that your parents don’t know everything. And in passing down what they do know, they can be unreliable narrators.” Did you have to get your parents’ consent to talk about them critically?

Sadiya Ansari: I’m sure the same would be true for anyone who has parents. [Parents] want to give you a version of the story that suits them, for a variety of reasons. Whether that’s not wanting to answer more questions from their children, or upholding family mythology consciously or unconsciously. And because there were these myths around my family being traditional and pious and educated and all these good things that in cultures like mine are so valued, when you dig a little deeper, you’re like, ‘Well, not everyone’s perfect.’ There’s this strange idea that we should all be perfect, in South Asian cultures in particular, and I don’t really understand why because in any family you find transgressions. That doesn’t make people any less worthy of love or respect.

I wanted to tell my family’s story without necessarily thinking of it as a criticism of them, but there are parts where I criticize my parents or my grandmother. My dad took it very well. I felt like he was my investigative partner; sometimes he was my executive assistant calling people and asking for interviews. But I was really surprised with the latitude he gave me.

More on Broadview:

SB: Have your views on feminism changed…especially when you take culture and history—like Pakistani traditions and the effects of partition—into consideration?

SA: The one thing that I really thought about while looking at my grandmother’s life from a feminist perspective was agency: What kind of agency did she have? What kind of agency do I have in my life? In contemporary discourse — especially if you’re in a privileged position, as I am; I have a lot of freedom compared to her — mainstream feminism presents itself as having solved the problem of agency or choice. But current discussions on marriage and motherhood, for instance, show us that we haven’t.

In theory, we want women to have power and agency. But in practice, that’s not really true in those structures. If you’re outside of wifedom or motherhood, your value as a woman is just not the same. It seems like becoming a wife or a mother, for some people, can mean giving away some of your power. And then not becoming those things can also means you don’t gain a certain other type of womanly power.

SB: Through writing In Exile, have you changed your perspective on motherhood and wifedom?

SA: I have two nieces, and I love them to bits. But I just think what parents have to do in our society is really difficult. I don’t know if I could do that and write another book, for instance. At the end of the day, it’s like that cliché saying, “You can’t have it all.” So, what do I want more? I think the conclusion I’ve come to is, if I really wanted to be a mother, then I’d probably have done that already.

With wifedom, I used to think of it as something that seemed very suffocating. But my perspective on that has changed. I think that partnership can be something that is mutually beneficial. But I’m not going to be installing my white picket fence anytime soon.

SB: Have you learned anything that has brought you closer or further away from Islam in the process of researching material for this book?

SA: Less so with regards to religion and more when it comes to culture and historical context. The depth of the research I did is not 100 percent reflected in the book, but I had to go really deep to understand. I started at the beginning of colonization in India, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of years ago, and asked myself what that does to a society when it’s been embedded for so long. Writing the book helped me understand the dynamics of religion and society and how things became so fractured.

SB: What do you think Daadi would think of the book?

SA: I didn’t sit down to write this with an idea of the kind of person I wanted her to come across as. I just knew that she was a really complicated person. But in every grandmother is a complicated person. Arundhati Roy once spoke about the kinds of characters she writes about: people that you sort of walk by, like a security guard or maybe someone who’s asking for money on the street, and you don’t think about them again. I think grandmothers are a similar type of person. Older women are often ignored, and their lives are never really dug into. I hope that she would feel like, at the very least, that her life was something that I thought was very worthy of recounting.

SB: There is a recurring theme of leaving or fleeing. You left Canada a few years ago. What are your thoughts now on the idea of leaving your community to find yourself?

SA: Canada is always going to be home. Ultimately, it’s the place where I’ve spent most of my life. It was less about leaving to find myself and more about leaving to affirm myself. When you’re in a place where people are constantly reflecting who they think you should be, it’s very tempting to just become that. Leaving gave me the space to tune into what I really thought and felt and gave me permission to wonder, what does another type of life look like for me?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

Sheima Benembarek is a Moroccan Canadian writer, freelance journalist, and magazine publishing professional.