“Our Fathers, who art in heaven,” I would pray after Dad died, ducking the metaphoric lightning bolt. Although I was a teenager then, I still harboured childish thoughts. I imagined the God of Protestants mad at me over this minor blasphemy, but I was angry with God, too. Thanks to Him (and back then, God was a Him), my dad also dwelt in heaven. And so I’d add, bitterly, “Who wants to hang out on a cloud with a stringed instrument anyway?”

My father has been dead more than 50 years — the length of time I’ve been separated from organized religion. Yet my ongoing, one-sided dialogue with a Supreme Being indicates I haven’t been completely weaned from God.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

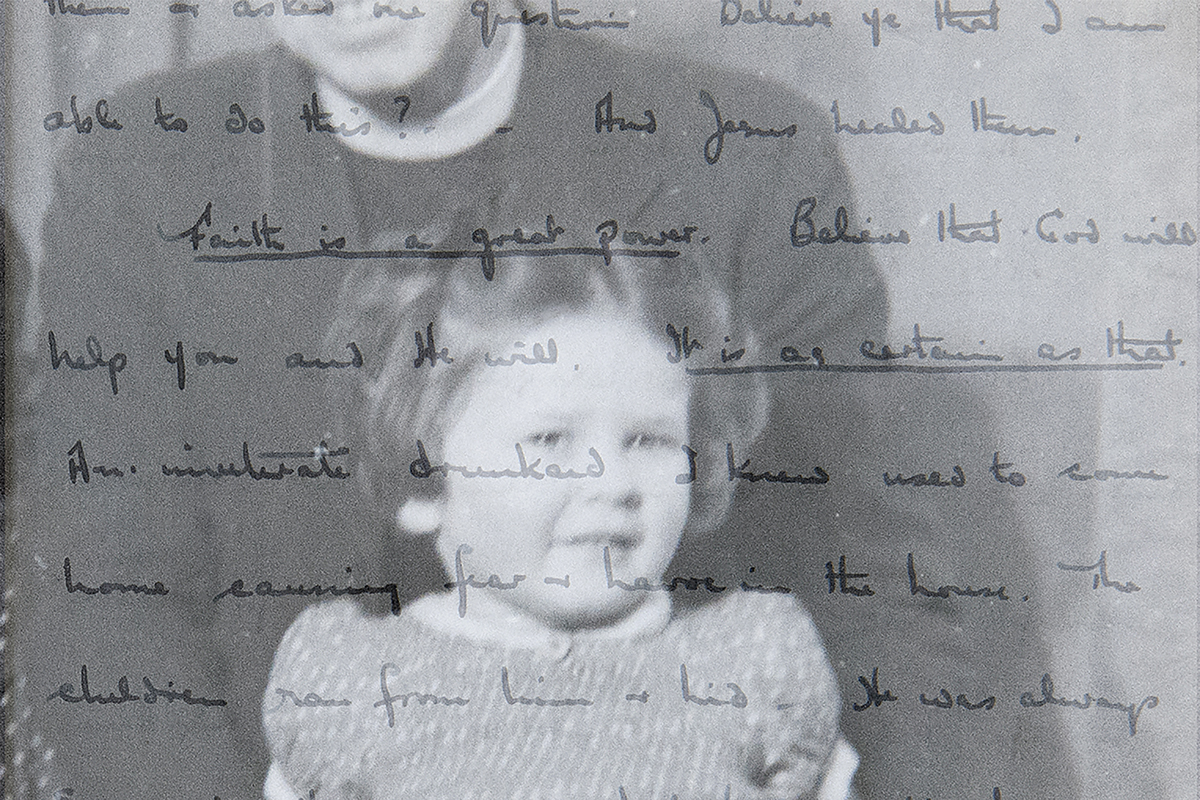

I was a child of the 1950s, a preacher’s kid, a “PK” in the vernacular. My dad was a United Church minister, socially outgoing with a vibrant personality. However, because of his job, we stuck out in our small Prairie town. My friends’ dads had bosses who were visible; my dad’s boss was a spirit —invisible.

I agonized about this, but it didn’t bother Dad. He sometimes talked as if God were in the room. I, on the other hand, was a doubter, incapable of making that leap of faith.

Amazingly, I don’t remember my parents questioning my belief — perhaps they took it for granted. I tried to communicate with God, but He never spoke to me, not once, not privately, not ever that I could hear.

The Old Testament terrified me. The New wasn’t much better. Stories of God’s bullying stuck in my head like bubble gum to pavement. The nightly prayers hinting I may die in my sleep kept me awake as I fought to suppress a jumble of morbid biblical images: Herod’s soldiers murdering babies; sinners frying in hell; Lot’s wife turning to salt; Abraham’s knife at Isaac’s throat; Job’s torment; sparrows falling to their deaths, according to a popular hymn, as God looked tenderly on. Way to go, God.

Although Dad was liberal and forward-thinking, I somehow conflated him with the disciplinarian God I feared. Father was powerful. The Father was all-powerful.

I resented the Almighty for creating a world that contained evil. Being all-knowing, He surely would have foreseen at the outset what would happen. Why tempt Adam and Eve, then punish everyone ever after? God had explaining to do before He got my soul, and sending Jesus in to save the day didn’t let Him off the hook.

If I’d had the courage to ask Dad about these matters, he might have set me straight. Years later, a girlfriend of mine told me she’d challenged my dad about similar biblical mind-twisters, and he’d explained symbolism and metaphor to her. She said Dad had inspired her to become a poet. How I wished she’d told me sooner.

For reasons that made sense at the time, I didn’t confide in my parents. The stakes seemed too high. Some of my fear stemmed from my Sunday school teacher, a teetotaller who convinced me that wicked thoughts, even mild ones, were a one-way ticket to hell. No special dispensation for ministers’ daughters. My guilt was huge. And why ruin everything? What if, by revealing a traitor in their midst, I got punished with more religion?

I bottled up my doubts, joined Brownies and Canadian Girls in Training, and attended Bible camp. I played my PK role like a movie star while feeling lost in the wilderness of the wrong family. Disguising my true self, whoever she was, was exhausting. Only God, if He existed, knew my secret.

If my internal life was in turmoil, my social life wasn’t much easier. I was expected, in my mother’s words, “to set an example.” I bristled at this condition, which flew in the face of everything I needed. Which was to have friends. On Earth.

In elementary school, PKs were outsiders till deemed otherwise. Thankfully, I had a funny side, which saved me. I did well in class, not brilliantly, my energies diverted to acting up just enough to get an occasional detention. Soon after I’d been given a warning for passing notes in class, Dad announced we were moving to a bigger town.

He promised street lights, two cinemas, a new batch of kids. I anticipated a fresh start, in obscurity. My hopes were dashed when the new Grade 4 teacher introduced me as “the reverend’s daughter.” She seated me, conspicuously, in the row with the best students. Clearly, God was determined to kill my social life. I proved I wasn’t an angel by learning to smoke cigarettes in the neighbour’s garage (a habit I kept until my mid-30s).

Dad wore a trim moustache and had dancing blue eyes full of conviction. On weekdays, he spoke in a normal voice and had an infectious laugh. He kept a Navajo pottery jar in his study for pipe tobacco and had beautiful oak bookcases with roll-up shelves lined with Bibles, fine literature and, in behind, a couple of risqué-looking paperbacks I was dying to get my hands on. In his spare time, he golfed, acted in my mother’s plays and recited poetry. Like Jesus, Dad was a great carpenter. He built a dollhouse for my sister and me, as well as our lakeside cabin and our boat, Crafty.

On Sundays, he donned his black robe and starched white bib and rushed in and out of the house between sermons and his radio broadcast. He had so much energy compared to the day, which seemed to drag on forever. Four hours till evening service. Tick-tock. My friends were out skating while we ate leftovers and rested.

Things could have been worse. I was United Church, milder than Anglican. I might have been a Salvation Army kid compelled to bang a kettle drum.

In the pulpit, Dad seemed remote, his preaching reminding me of the things I was supposed to believe in and couldn’t quite. He had a gift for speaking, and although he told stories from real life as well as from scripture, I got stuck in “thou shalt nots” and evildoings. I was happy to sing in the choir: music was my joy. I also liked when Dad made jokes. I wanted more of that dad, but he was too busy to hang out and laugh with us. Most nights, he was off practising what he preached, consoling others. When he was home, he’d be at his desk preparing one of three weekly sermons. My dad always had new things to say about God.

Heaven, our reward, held no comfort for me. I was a city girl. Paradise, meanwhile, was pastoral: Jesus was a shepherd; father led a flock. I already knew what it was like to spend eternity on a farm. For a month each summer, my brother, sister and I stayed with family friends while our parents drove off to California on holiday. I remember my sinking heart as their Chevy disappeared in a cloud of dust. I tried to feel excited about the countryside: heat rising off the fields, bees buzzing, chickens getting slaughtered, the two-seater outhouse and nothing but land, sky and horizon as far as the eye could see. But I couldn’t.

No, if there was an afterlife, it had to be a place with all the sparkle and glamour I was missing. Not a club where certain people weren’t welcome.

Catholics would likely qualify but not my maternal grandfather, a Burmese Buddhist I had yet to meet. Nor would my friend Rivi, who was Jewish; nor babies unless they were baptized; nor unwed mothers; nor African Bushmen pictured in the pages of National Geographic who may have never heard of Jesus. Not knowing Jesus was no excuse. He said so himself in John 14:6: “No man cometh unto the Father, but by me.” That was contrary to everything I held fair and dear.

As the minister’s family, we lived in a manse. All our furniture, including the scratchy green sofa, was owned by the church. Dad worked overtime, and people arrived at all hours seeking help. When the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Mormons knocked on our door, Dad often invited them in to hone his skills. It was funny to watch them squirm. Dad’s sport was to joust over scripture, and he always won.

Once, Dad adopted a drifter named Earl, who rode into town on a boxcar and lived with us for six months. Earl vowed to stop drinking and help Dad finish the rec room in our basement.

I resented Earl and the kindness my father showed him. I dreamed of showing up like a stranger — a sinner — and being showered with affection. How was it fair that Earl, who’d lived the wild life, was rewarded with Dad’s free time on Saturdays?

Earl was crazy for Hank Snow’s version of It Is No Secret (What God Can Do). He played that record till Mum begged him to stop. Then, one day, he fell off the wagon and disappeared. Our house was gloomy for a while. Dad missed Earl, but I think Mum was relieved.

When I was in Grade 6, I watched from my bedroom window as the Foursquare Pentecostal manse, two blocks away, went up in flames. It was a scary, thrilling sight. The freckle-faced PK who lived there was in my class. She pitched on our softball team. The fire made her a local hero. I asked my parents if she could stay with us while her family found a new house, and they agreed.

We made a pact to attend each other’s churches on alternate Sundays. It would be adventurous, I thought. I was curious.

The Pentecostals waved their hymnals; they exclaimed, “Yes, Lord!” and “Amen!” I was okay until her dad invited people up to the front to repent and have their sins washed away. She tugged at my arm while I clung to the pew in terror. My heart slammed in my chest as she released me and went up alone.

Outside, she told me I was going to hell. I didn’t need her to remind me, but I was stung. I hated her guts. I never wanted to see her again.

I told my parents what had happened, and — miracle! — they took my side. I felt understood, almost happy.

It was the second time they’d stuck up for me. Previously, my teetotalling Sunday school teacher had handed out pledges to sign that we would never touch liquor or cigarettes in our lifetimes. I had already tried smoking, and I knew my dad enjoyed the occasional drink, so I showed him the pledge. He promised to take care of it. The pledges were never mentioned again.

Meanwhile, the Pentecostal PK and I maintained a frosty truce, but her condemnation remained with me for a long time.

My early teens held more spiritual angst. The pressure was on to get confirmed. I tried putting it off, but Dad said no, it was time. I was miserable about having to pretend but went along for his sake, sipping the grape juice, crossing my fingers and praying (yes, praying) that Jesus would understand.

Over the next few years, I grew mildly rebellious within the confines of my fishbowl. I hung out with boys in smoky cafés. I became embarrassed by Dad’s wardrobe. When he wore his clerical collar on weekdays, I’d cringe. Why advertise? I’d think. Peter may have denied Jesus three times, but I betrayed my dad a thousand times more. Could I ever be forgiven?

When I was 16, my dad died during a violent thunder and lightning storm at the lake. I was at the dance one beach over. Dad had been against my going. He caved because my girlfriend in the cabin next door had permission, and her dad, Mr. Wilkins, a church elder, promised to pick us up.

When the storm worsened and waves threatened his handcrafted boat, my dad, aged 48, ran down the beach to save it and suffered a fatal heart attack.

I was jiving to a rock ’n’ roll band. The storm was causing the lights in the dancehall to flicker on and off when Mr. Wilkins appeared in the doorway, too early. He said, “It’s your dad.”

By the time I arrived home, the electricity was gone. Our family huddled by a kerosene lamp, crying in disbelief. Our invincible dad lay on the couch, covered by a bedsheet. Was he with the angels? God, having “called Dad home,” was nowhere to be seen or heard. Was He in the howling wind and the slashing rain? Or was He in the neighbours who came to offer consolation while we waited for the ambulance that couldn’t get through until morning? The power, it seemed, was out everywhere.

Terrible and painful as it was, Dad’s death liberated me. Along with grief, a burden was lifted. My dual life had been threatening to pull me under; I saw no way out and started having the panic attacks that would continue for years.

After the funeral, I confided in my mother. Mum accepted my views, even shared some of them. God was more a divine light inside all of us, she said. She admired my father’s incredible faith, but she still struggled and Dad understood. If only I’d talked to them sooner, especially about my obsession with a punishing Old Testament God.

Before we sold Dad’s car, I “borrowed” the keys. Dad didn’t allow me to drive alone, even though I had my licence. With authority gone, I took it for a spin. It felt dangerous and exhilarating. I drove carefully, respectfully, around a few city blocks.

Just once.

Later, I came to understand that ride as a metaphor. Unprepared for freedom, constraints gone, I hesitated by the open door, trying to imagine my life. Therapy would help me with that over time, as well as how to cope with loss.

We were a product of the times: me, Dad and God. Change was happening. Institutional religion was loosening up; children were being heard.

Half a century on, have I found answers?

Some. I have Dad’s spiritual side, and I remain open. I believe in creativity and beauty, in acts of kindness and love. Maybe even in God.

I wish Dad and I could talk now, as adults and equals. How I wish. I believe he would enjoy jousting with me, as he did with the Mormons and the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

By a fire, over a glass of wine.

This story was originally featured in The Observer’s January 2018 edition with the title “Me, Dad and the Almighty.”