The coastal sun is brilliant as the float plane I’m riding in touches down on the waters of Victoria’s picture-perfect harbour. It’s late June, and tourists swarm the docks en route to whale-watching excursions. Crew members unload my luggage from the plane, and then I sit along the sparkling waterfront and wait. Eager to make contact with the man I’ve travelled over 3,000 kilometres to meet, I phone Don Hume. “Be there in five minutes,” he says.

Hume, a former United Church minister, claims he acted on impulse when he typed out a letter and mailed it to The Observer in May. Enclosed was a copy of a testimonial he delivered recently at a Unitarian Universalist congregation in Victoria. It begins: “My name is Don Hume. I am a drug addict who used crack cocaine and crystal meth. I was 60 years old when I started doing drugs.” The letter describes his fall into drug addiction and his subsequent departure from the United Church. In the first paragraph, a revision or afterthought appears as a single line in a smaller, darker font: “There is no fool like an old fool.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

I found Hume’s letter intriguing, to say the least. Here was a minister who, nearing retirement, had somehow found himself in a position to try crack cocaine. More incredible still was his decision to go through with it. What did he expect? Anyone remotely familiar with crack could imagine the likely outcome: he underestimated its powerful effects; he began to use more often; his life became a jumble of regret, exhilaration and despair; he lost everything. The unusual twists of Hume’s age and profession aside, it was a sad, familiar tale.

Don Hume’s second act held more inspirational potential. Having seen life’s darker side, he enters into treatment, walks the winding path of recovery and finds himself on a higher spiritual plane. It was a story of redemption, the kind we long to hear.

Or at least this was the tale that had taken shape in my mind. It turns out the real story was far more complex, its moral far less certain. It began out there on the Victoria harbourfront.

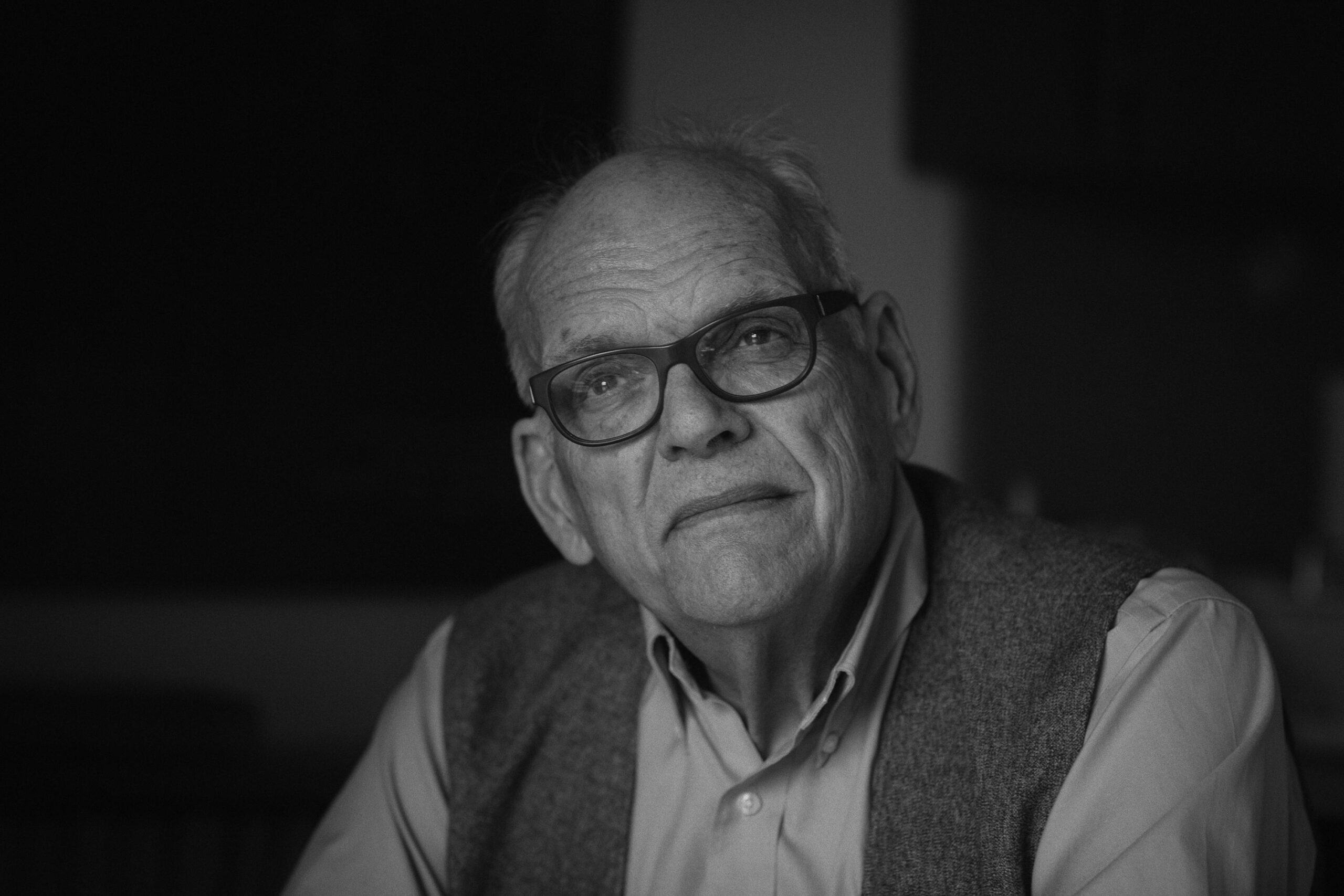

“Justin?” A squinty-eyed gentleman stands before me, one hand firmly on his hip. He looks several years older than I had imagined. Weeks earlier, he mailed me a photo of himself with a goatee and a rippling smile. I assumed it was recent. But now his face is clean-shaven and sunken in. He’s a few pounds lighter and wears brown-framed glasses with a green sweater vest. He holds a four-pronged cane with a psychedelic design. And his cargo shorts stop short of covering his leg tattoo, acquired on a whim in Mexico. He started having second thoughts during the procedure. But things done on impulse cannot always be undone.

The Don Hume I meet is kind and thoughtful, a 74-year-old with heart problems who seems pleased to finally shake my hand after weeks of long-distance phone calls. I throw my bags in the trunk, and we are on our way. En route to his apartment, he bypasses traffic by zipping down side streets, becoming disoriented. As we drive, he shares details of people’s lives that I couldn’t possibly report here. I’ve known him for scant minutes, and it’s as if I’m his closest confidant.

The next day, I find Hume waiting for me in the hotel lobby. By the time we get to his car, he’s out of breath. He drives me to one of his “haunts,” Belleville’s Watering Hole & Diner, facing the harbour. It’s another brilliant day, so we sit on the patio, and he continues his tale.

Hume was born in Winnipeg in September 1943. An only child, he was a teenager when his mother died suddenly of cancer. “My dad never shed a tear; he was very stoic about everything,” he recalls. His parents weren’t religious, but he was sent to Sunday school — “like you’re supposed to be, when you’re a kid” — and he became involved with the Young People’s Union. At the time, he didn’t care much about the church’s social justice mission; it was the promise of community that appealed to him. When he began thinking about ministry, his dad told him, “Don, you’ll become a doormat to everybody in the town you’re in.”

One night, about two years following his mother’s death, Hume returned home to the apartment he shared with his father after going to the movies. He sat down to read; his father’s wallet and watch were on the table beside him. It didn’t dawn on him that something was wrong. The bathroom door was closed. Inside, his father had fallen against it. Hume called emergency services and dragged his father’s lifeless body out into the living room. He was 19 years old. He says, “Some people say I’m a bit fixated with death, and I think that’s true.”

As a young minister on student placement in Vernon, Man., he fell in love with Ruth Reid, a former Christian education director in Winnipeg, with whom he had been friends for several years. They quickly got engaged and visited her parents at the cottage to deliver the good news. Standing out on the lawn, Ruth said, “Mom, I want you to meet Don Hume. We’re engaged to be married.” Her parents were incensed, but the couple got married anyway, six weeks later. Hume missed the first part of theological school in Winnipeg because he was on his honeymoon. The dean was not pleased. “I didn’t know what the hell I was doing,” Hume now says. He later completed his studies at the Vancouver School of Theology.

Don and Ruth had two children: Chris, who repudiated religion at a young age; and Irene, an evangelical Christian like her mother. The couple separated several times before divorcing when their kids were teenagers. Early in his career as a United Church minister, Hume worked as a social worker at the Western Institute for the Deaf, as a minister at Kitimat (B.C.) United and as a counsellor in Vocational Rehabilitation Services in Vancouver. In the early 1990s, he married again. In 1995, Hume began working at James Bay United in Victoria; his spouse continued living in Vancouver. They lived apart for many years and divorced following Hume’s retirement in 2005.

Around that time, Hume says, he was offered crack cocaine, a crystalized form of cocaine that is usually heated and smoked, as well as crystal meth, a synthesized stimulant that can also be smoked. Both are highly addictive. “Thinking I am a strong-minded person [and] I can do it once or twice and end it, I accepted the offer,” he later confessed in his letter to The Observer. The experience was more powerful than he imagined. “My mind lifted out of my mundane life, and I became a powerful force capable of anything.” At first, he used the drug about once a month. Then it was every few weeks. Then every few days. Before he knew it, addiction had a grip on him.

The circumstances that led to that first experience with hard drugs in Victoria are unclear. The story changes according to whom you ask. Chris told me his father became involved with drugs by working with people on the street. “He’s the guy trying to help them,” he says, “and then they ended up taking advantage of him.” They “would kind of prey on Don. Get their hooks into him, get him to give them money.” When Hume suddenly started losing weight — he became thin and “gone looking” around his arms and legs — Chris worried he might have AIDS. He asked his dad about it, but Hume was evasive. After being pressed, Hume blurted out, “No, I’m a crack addict!” Chris says, “It took me almost a week to digest that.”

Some of Hume’s acquaintances believe he got caught up in drugs by trying to identify with Chris, who admits that he’s a functioning drug user. In Vancouver, sometime between 2005 and 2007, Hume staged an intervention for his son in the office of St. Stephen’s United, where he worked as retired supply. Chris didn’t know that his father was also using at the time. The family convinced Chris to enter rehab; his parents paid the $4,000 monthly fees. Mere weeks after getting clean, Chris was using again. “I didn’t stay clean for very long at all,” he says. “I didn’t want to be in recovery. I was bored. Bored, bored, bored. All the time.”

Hume used to tell people that he got to be curious about his son’s affection for drugs. But he now says blaming it on wanting to know what Chris was up to “was a cop out.” He had met drug users over the years, had been told that drugs could induce, in his words, “intense feelings of power and authority and understanding and wisdom and smartness and sexual prowess.” Eventually, “no” turned into, “Hell, I’ll just give it a try.”

Hume’s openness is unsettling. He frequently veers into deeply personal anecdotes that have no real bearing on our main discussion. The more he speaks, the more the redemption story I had envisioned crumbles. Our server approaches. Hume had ordered a shandy — half beer, half ginger ale — and asked her not to skimp on the ginger ale. But he hasn’t finished the first one, and that arrived over an hour ago. This frail septuagenarian is getting sleepy. He tells me he still smokes crack on occasion. I struggle to imagine how.

In 2005, Hume, then retired, began serving as a supply minister at St. Stephen’s United, a small congregation in an affluent neighbourhood in south Vancouver. His drug use remained a secret to everyone except a handful of close friends. Hume says that at the time, “It didn’t bother me too much, other than the fact that I had slight guilt feelings about it.” St. Stephen’s was an aging congregation in “real need of pastoral care and love and gentleness,” says John Keenlyside, chair of the church’s board. When Hume arrived, Keenlyside says the church was “feeling a little bit needy. And [Hume] came in with a really bouncy, warm, generous spirit.” His presence was felt immediately. One of his first mornings at the church, Hume walked in and declared, “All right, I’m here! Who needs a visit?” Keenlyside describes Hume as an “ebullient” pastor who has always taken care of those in need.

Not everyone saw the other side of their minister — the Hume who once found his car missing around 2:30 a.m. Two men — one of whom was his drug dealer (“kind of”) — had stolen his car and were demanding $500 in exchange for its return. He was threatened with a knife and taken to a bank machine. Hume was sure he was going to be killed that night, but Vancouver police intervened.

Some members at St. Stephen’s privately suspected not all was right with Hume. Yet they protected him out of a sense of loyalty and respect for his privacy.

Hume’s personal struggles became public after he began working at Oakridge United, also in Vancouver, in September 2007. “That’s when I began to feel that I was using far too much,” Hume says. “I was in trouble, and I was getting very upset with myself.”

His work suffered. Rough-looking types were reported around the church. There was talk that he had become overly friendly with an elderly female parishioner. Doug Golding, the treasurer at Oakridge United, says he heard Hume was seen drinking wine with a woman in the office and was caught walking around in his pyjamas. Some believed he had started sleeping at the church.

By this time, Hume had tried to get help. He had attended sessions with a drug and alcohol counsellor, but was still using when they finished. Depressed, he drove to Vancouver’s Stanley Park. It was a Sunday afternoon in August 2008. He parked his car, walked into the woods and sat on a log. “I was sure my dirty secret was on the verge of being exposed. I was a failure as a professional, as a father, grandfather and friend, and I could not stop the train of addiction,” he wrote in the testimonial he sent to The Observer. He hadn’t driven to Stanley Park with the intention to commit suicide, but he was feeling desperate. He did some meth, took a handful of sedatives that his doctor had prescribed to settle him down, and fell unconscious.

He may have died had it not been for the elderly parishioner (now deceased) with whom he had become so close. Hume was supposed to meet her for lunch the next day. When he didn’t show up and when she didn’t hear from him in the hours and days that followed, she convinced Chris to call the police and report him missing. Hume remained unconscious in the park until Wednesday, when police returned to a location from which his illegally parked car had earlier been towed. They found him in a state of hypothermic stupor.

The members of Oakridge United did not see Hume again. While he was in hospital, an official from Vancouver-South Presbytery visited and told him that church officials were now aware of his situation. The two discussed what would happen next. Hume understood it as an ultimatum: resign or be removed. “There was no hearing,” he says. “And I was not given any choice.”

Treena Duncan, personnel minister for B.C. Conference, says they came to the “mutual understanding” that Hume would be placed on the voluntary Discontinued Service List (DSL) and that he would be restricted to the same extent as someone placed on the DSL for disciplinary reasons. “It was an arrangement that was made in order to allow him to pursue recovery,” Duncan says. “I guess what I’m trying to say is we should have put him on the DSL disciplinary, but we were trying to be pastoral.”

The day after our drinks on the harbourfront, we’re sitting in Hume’s bachelor apartment. A small hospital-like bed faces the television. Earlier, I called him to confirm our plans. That’s when he offered to take me to a shop where I could purchase a crack pipe as a “B.C. souvenir.” Thanks, but no thanks.

Now in his apartment, I ask him about his version of events and give him a chance to respond to claims made by others.

Someone said you were having an affair with an elderly parishioner.

“[She] was very angry about it. So was I. Absolutely not true.”

Did you ever meet with drug dealers at the church?

“No.”

And you never slept there, either?

“I would sometimes go to the church early in the morning, but I never slept in the church. I had an apartment.” Later in the conversation, he admits it’s possible he went there and accidentally fell asleep

The next day, he phones me with a small confession.

“I loved the office [at Oakridge]. I went to it as kind of a retreat. I went often. I could see where people could see me as misusing it.” He mentions a contractor who did a terrible job on his apartment, but he doesn’t finish the thought. I learn later that his apartment was virtually unlivable at the time. The implication is clear: he may have stayed at Oakridge in the interim.

As much as I want to believe him, I really don’t know what to make of the man. My skepticism grows after speaking to his daughter, Irene. “I never really heard exactly what the real truth is,” she told me of her father, “because my dad distorts things the way he wants to remember [them].”

We tend to see everything in binary terms, as black or white — and to condemn or defend accordingly. I journeyed to Victoria hoping I would uncover some basic facts on which I would build a story: Hume was either a recovered drug abuser who had been heartlessly dismissed from the church (as he claims he was); or he was a deeply damaged soul who embodied the perniciousness of addiction.

I knew my investigation carried risk. It could tear open old wounds or pave a healing path. It could point to a larger truth or embarrass church bureaucrats — or, more likely, Hume himself. When I got down to it, I often sensed the truth was being obscured by the limits of memory, goodwill toward a friend and former minister, and genuine uncertainty. Guarded by half-truths and excuses, drug users can become strangers even to their families and closest friends. Still, I continued to believe that, in the end, a clear picture would emerge. Some event, person or obvious character flaw could explain what happened to Hume.

In conversations with Hume before I went to British Columbia, he urged me to read Dr. Gabor Maté’s 2008 book, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. Maté is a renowned addiction expert from Vancouver who considers himself an addict — a compulsive classical music shopper who once left a patient in labour to run to the music store. During my five-hour flight to Vancouver, I pulled the book from my carry-on and started reading: “I have come to see addiction not as a discrete, solid entity — a case of ‘Either you got it or you don’t got it’ — but as a subtle and extensive continuum. Its central, defining qualities are active in all addicts, from the honoured workaholic at the apex of society to the impoverished and criminalized crack fiend who haunts Skid Row.”

Maté, who favours harm reduction over “curing,” maintains that addiction results from stunted childhood development brought on by abuse, trauma or lack of parental love and attachment. Our early experiences shape how our adult brains are wired; given the same addictive substance, some of us will become addicts, while others won’t. This theory got me pondering Hume’s addiction: his father’s emotional distance, the untimely deaths of his parents. But who was I to dissect him this way?

Maté believes that a full recovery is unrealistic for some drug users. Not everyone can quit cold turkey. Having read Maté’s book, I found myself unexpectedly sympathetic to hear from Hume that he still occasionally “slips.” In his initial letter to The Observer, he wrote that he had been clean since 2015. But asked about this in person, he confessed, “I haven’t had a major slip since 2015. I’ve had a little bit here and there, couple of times. But it’s not like I’m using continually or all the time, and I usually just say, ‘Okay, you’ve done a little bit, Don. Get the hell out of this. Stop.’” There was a time when Hume would get “really angry” at the suggestion that he will always be an addict. But he’s come to believe that it’s “part of my title now. On my obituary, it’ll just say, ‘Don Hume, drug addict par excellence.’”

It’s the Sunday of my return to Toronto, my last chance to meet with Hume. I sit among some 35 members of the Capital Unitarian Universalist Congregation in Victoria’s James Bay district. The blistering heat may be to blame for the small turnout. An opening word reminds us that all are welcome — no matter your gender, age, sexual orientation, race, religion, life story. This is the congregation that has welcomed Hume with open arms. He suggested I attend the service as part of my visit to Victoria.

Some time after leaving the United Church, Hume started attending Capital. Unsure how he would fit in as a Christian, he took his time before becoming a member. He used to joke that Unitarians are “godless heathens,” and still questions their ways and occasionally asserts his Christian beliefs. Still, the Unitarians seem to have accepted Hume as Hume. It was here that he first shared his secret in the form of a testimonial: “My name is Don Hume. I am a drug addict who used crack cocaine and crystal meth.”

Following the service and reception, members of the congregation gather in the next room to share thoughts on the subject of today’s sermon, Taoism. It’s not easy for a hodgepodge of people from different faiths to discuss the merits of an ancient Chinese philosophy. But the youngest among us, a girl who appears to be in her teens, raises her hand to explain the principle of wu-wei — action through inaction — based on her studies of Taoism. Think of a single drop of water in a river running downstream, she says. The drop doesn’t move, yet the river flows.

I wonder what Hume would think of this. Would he congratulate the girl on her insightful contribution? Would he search for a Christian angle? Stay silent? Find it significant to his own story?

I will never know. Shortly before I arrived at the service that morning, Hume phoned me to say that he wasn’t feeling well and that he wouldn’t be joining me. I left without seeing him again.

This story first appeared in the October 2017 issue of The Observer with the title “Fall from grace.”

Thank you for your insightful article. I met Don briefly, when he was at Oakridge United Church. My husband had known Don from his days at the Vocational Rehab Centre. My husband and I wish Don well, and pray he is able to find peace and clarity.