(RNS) — A phrase from the Book of Deuteronomy hangs framed on the wall of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Supreme Court chamber: “Justice, justice you shall pursue.”

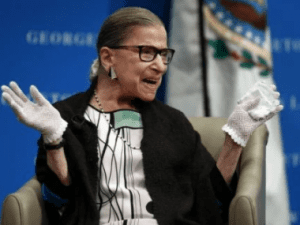

For Ginsburg, who died at home surrounded by her family on Friday evening (Sept. 18) at the age of 87, the phrase from the Hebrew Bible, “Tzedek, tzedek tirdof,” summed up perfectly her calling as jurist and a Jew.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“Our nation has lost a jurist of historic stature,” said Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. in a statement released by the Supreme Court. “We at the Supreme Court have lost a cherished colleague. Today we mourn, but with confidence that future generations will remember Ruth Bader Ginsburg as we knew her — a tireless and resolute champion of justice.”

Ginsburg, who had remained on the court despite suffering a long series of health challenges, rarely attended services, but she was passionate about Judaism’s concern for justice and was shaped in the crucible of its minority status.

Nominated to the high court by President Bill Clinton in 1993, Ginsburg developed a cultlike following over her more than 27 years on the bench, especially among young women who appreciated her lifelong, fierce defense of women’s rights. Acquiring the moniker “Notorious RBG” as she got older, the 5-foot-1 justice who decorated her robes with lace collars was viewed as a model feminist who successfully knocked down legal obstacles to women’s equality and levelled the playing field between the sexes.

But as a justice, Ginsburg was dedicated to equality not only on behalf of women. She cared as deeply for minority groups, immigrants, the disabled and others.

More on Broadview:

- Martin Gugino is back on his feet and determined to protest

- Katherine Hancock Ragsdale on the fight for reproductive justice

- Gifts of food in moments of crisis help ease caregivers’ burdens

In this, her identity as a Jew played a big role.

In a 2018 interview with Jane Eisner, then editor of the Jewish daily Forward, Ginsburg said that she grew up in the shadow of World War II and the Holocaust and it left a deep and lasting imprint on her.

“She saw being a Jew as having a place in society in which you’re always reminded you are an outsider, even when she, as a Supreme Court justice, was the ultimate insider,” said Eisner. “That memory of it — even if it’s more from the past — informed what she thought society should be doing to protect other minorities.”

Or as Ginsburg said during that interview: “It makes you more empathetic to other people who are not insiders, who are outsiders.”

Ruth Bader was born in Brooklyn in 1933, the daughter of a furrier who arrived in the United States from Russia at the age of 13. Her mother was born in the U.S., months after her own parents landed in the country from Austria.

Anti-Semitism was commonly accepted in those days, and families like the Baders confronted the social difficulties of being Jewish while at the same time holding out hope that they could climb into the ranks of the middle class.

“Both parents were very eager that Ruth learn what it meant to be a good Jew and a good American,” said Jane Sherron De Hart, professor emerita of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who wrote a biography of Ginsburg. “That was a goal shared by a large number of Jews in Brooklyn who sought to assimilate in the sense of being good Americans but also retaining their Jewish heritage.”

Ruth’s mother, Celia, encouraged her independence and pushed her to excel. She had a list of “women of valour” — a biblical term referring to women who were wise and successful. Ginsburg imbibed those stories and memorized them, De Hart said.

“She very much believed in institutions and incremental change. That’s an outgrowth of her experience as a Jew.”

Just as Ruth was entering high school, her mother was diagnosed with cancer. She died in 1950, two days before Ruth’s graduation from James Madison High School in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn.

In keeping with Jewish custom of the time, Ruth was not allowed to say the mourner’s prayer for her mother as part of a minyan or quorum required for public prayer. Only men could be counted for a minyan, a tradition that has since changed in Reform and Conservative Jewish traditions.

The exclusion forever marked her relationship with religious Judaism.

“She was extremely indignant about it,” De Hart said. “She felt it was an affront to her mother, and there was nothing she could do about it. That was the end of her affiliation with the religious dimension of Judaism.”

She married Martin Ginsburg, whom she had met when both were undergraduates at Cornell University. The couple went on to Harvard Law School, though Ruth transferred to Columbia Law School after Martin took a job in New York City. They had two children, Jane and James.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, as she was now known, went on to teach at Rutgers and Columbia law schools and in 1972 co-founded the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union. She argued six gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court between 1973 and 1976, winning five.

No firebrand, she pursued a long-term strategy to chip away at discriminatory laws, one by one.

“She tried to work through the system,” said Eisner. “She very much believed in institutions and incremental change. That’s an outgrowth of her experience as a Jew. The law protected minorities — not all, and not equally — but there was a great reverence among the Jews of that generation in the power of government to protect them and pave the way for their achievement.”

In 1980, Ginsburg was nominated by President Jimmy Carter to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where she served 13 years until she was appointed to the Supreme Court.

Behind the scenes she tried in small ways to make the court more hospitable to Jews. Several Orthodox Jewish lawyers had complained that a certificate issued by the court read “In the Year of Our Lord.” For Jews, explicitly framing the calendar year as Christian was offensive. Ginsburg successfully urged the court to excise it.

She also pushed the court not to hear cases on Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, a practice that continues to this day.

Although the Ginsburgs were secular Jews, after Martin’s death in 2010, Ruth began accepting more invitations to speak to Jewish groups. In 2018, she received the $1 million Genesis Prize, awarded annually to a Jewish person for talent and achievement. (She donated the proceeds to various Jewish charities.) In 2019, Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History mounted a travelling exhibit of her life.

Ginsburg attended Washington, D.C.’s Adas Israel Congregation once a year for the Kol Nidre service on the eve of Yom Kippur, but she was never a dues-paying member.

Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt of Adas Israel said the Conservative synagogue extends free membership to all the Jewish justices on the court. (Justice Elena Kagan attends on the High Holidays as well.)

In 2015, Ginsburg was asked by the American Jewish World Service to write an insert to its Passover Haggadah. She agreed and asked Holtzblatt to help her research some of the sacred texts about women in the Exodus narrative.

True to form, Ginsburg wanted to write about the figures not mentioned in the Haggadah.

“For her that was all the people who were marginalized, like the women,” said Holtzblatt. “She wanted to highlight the roles they played. She wanted to learn more about the daughter of Pharaoh, Moses’ sister Miriam, and the midwives, Shifra and Puah. She and I talked a lot about people who are not given the spotlight when they do miraculous things.”

Holtzblatt said she never asked for a byline on the essay, because she only provided Ginsburg some source material. Ginsburg, however, insisted.

A private interment service will be held at Arlington National Cemetery, according to the SCOTUS statement.